Heavy losses for individual investors in pre-construction condos

What happens to the growing inventory of unsold condos?

Andrew Tobias’s book The Only Investment Guide You’ll Ever Need lives up to its immodest title. One of the first chapters, “Trust No One,” emphasizes an important principle: don’t invest in something you don’t understand.

Another key principle: the higher the return you’re aiming for, the greater the risk that you’re going to lose your money.

Ali Amad’s recent longform article on Toronto’s condo market opens with some stories from the perspective of individual investors who sank their life savings into a deposit on a pre-sale condo, only to see the market crash. In short, they underestimated the risk. They didn’t just lose their deposit - they’re getting sued by the developer, since they signed a contract to buy the condo at the pre-crash price. The Condo Crash, Maclean’s, August 2025:

In the spring of 2022, Nizar Tajdin, a 41-year-old Montrealer, signed a deal he thought would set him up financially for years to come. On the advice of a realtor he’d met through a friend, Tajdin made a 10 per cent deposit on an $855,000 pre-construction condo. It was a 468-square-foot, one-bedroom unit in Toronto’s Forest Hill neighbourhood, a wealthy enclave not far from downtown. The project was scheduled for completion in 2024. But Tajdin didn’t intend to move into the condo, or even to close on the deal.

Instead, he planned to flip it before it was completed. Tajdin’s realtor—an agent named Rahim Hirji, who advertised himself as a specialist in “platinum pre-construction condos”—had devised the plan. It was called an assignment sale: the legal transfer of a purchase agreement to another buyer before closing, at a higher price than the seller originally paid. In essence, it means flipping a condo that doesn’t yet exist. Assignment sales had become a common hustle in the booming Toronto condo market. Tajdin says Hirji told him that he could make back double his deposit; he even offered to find a buyer in exchange for a fee.

Tajdin knew when he signed the contract that if he couldn’t resell the condo before completion, he couldn’t get a mortgage to pay the developer.

That’s exactly what happened. Shortly after signing the contract, the Bank of Canada raised interest rates sharply to cool inflation. Market-clearing prices dropped. Tajdin couldn’t complete the deal. The developer sold the condo for $420,000, and then sued Tajdin for the rest, plus damages, legal interest, and legal fees. He’s now facing bankruptcy.

I thought Amad was remarkably sympathetic to investors like Tajdin:

Tajdin is one of thousands of Canadians who have been caught in the fallout of the country’s collapsing condo market. Many are middle-class buyers who fell victim to the relentless real estate hype machine. They were told that big-city condos were a surefire place to park their money—and they were the biggest losers when the floor dropped out of the market.

Betting on prices continuing to go up

How much is a condo worth? It’s the value of the stream of future rents that you can either collect (if you’re an investor who’s renting it out) or that you don’t have to pay (if you’re living in it).

Judged by this measure, Toronto condos have been overpriced for quite a while. Rachelle Younglai, writing in the Globe and Mail, observed that in 2022, according to Urbanation, half of investors who took out a mortgage to buy a newly completed condo were paying more in monthly expenses than they were receiving in rent (“negative cash flow”), with an average deficit of $220/month. By 2024, the number had reached 80%, with an average deficit of $600/month.

Why were people willing to pay such a high price? What were they thinking? Short answer: expectations. They thought that prices would keep going up. It’s basically the “HODL” strategy: hold on as long as possible, losing money every month, and then make money when you sell.

Tajdin’s assignment-sale approach was one step beyond that. He wasn’t just betting that prices would go up in the long term. He was betting that they would go up in the next two years: an even riskier bet.

Speculation as time-based arbitrage

My understanding of speculation (from Joseph Heath) is that it’s similar to arbitrage, based on time rather than location.

With arbitrage, you’re buying something in a place where it’s relatively abundant and therefore cheap, and selling it somewhere else, where it’s scarcer and therefore more expensive. This helps to move it to where it’s needed.

Similarly, with speculation, you’re buying something when you think it’s relatively abundant and cheap, and planning to sell it in the future, when you think it’ll be scarcer and more expensive. This helps to move it to when it’ll be needed.

The basic problem here is, there’s nothing physically stopping us from building more apartments. As recently as 2013, Kerry Gold was reporting the lamentations of condo owners that condo prices had been stable or declining (after inflation) for the previous five years.

Mr. Hynes paid $182,000 for his condo [five years previously], which was $7,000 below the asking price. He was thinking of selling the unit until he saw that his neighbour on the same floor, with the same suite, has just listed for $179,000.

"I thought it would at least keep its value, so I'm surprised," Mr. Hynes says. "If it had kept its value, I definitely would have sold right now."

He says his work colleagues, friends and relatives are facing the same situation. His cousin just sold her condo after renting it out for five years, and she lost money on it.

"It was for the exact same reason I'm losing out," Mr. Hynes says. "Because there are so many condos in the area."

There are too many new condos. Since the economic slump of 2009, condo starts have been on the rise, and above the 20-year average ratio of starts-to-population growth. Developments were going up almost as if it were 2007 again.

“Past performance is not an indicator of future results”

A year ago, Deny Sullivan observed that (a) betting on GTA condo prices going up has been successful in the past, (b) making this bet by putting down a 20% deposit on a pre-construction condo is a 5X leveraged bet, and (c) this is an extremely risky way to fund construction. The Folly of Pre-Construction Condos, August 2024.

How condo prices in the GTA have increased over the last 20 years or so:

With 5X leverage, this is what return on investment looks like - and what it looks like for investors who made this bet in 2022:

He concludes:

The takeaway is that Ontario’s obsession with condos & pre-construction financing is a mistake. It’s a mistake that worked tremendously well for 15 years, but it is and was still a mistake. It’s a mistake that will be painful for many for years to come. And the sooner Ontario stops expecting mom & pop investors to make wild, leveraged bets to fund its construction industry, the better.

Mike Moffatt suggests that the revival of the MURB program will direct individual investors to purpose-built rental projects instead of condos. This is a straightforward way to defer taxes, through accelerated depreciation (over 10 years rather than 25 years), so it’s much less risky than speculating on future condo prices.

Think townhouses, three to six-story apartment buildings, and so on. If you drive in any city in Canada and see an apartment building from the late 1970s, chances are they were built through this program. Typically, it wasn't a single investor who would build these things, but a consortium would get together. So, you get a bunch of well-off doctors, dentists, lawyers, and so on, who would pool a bunch of money together and build one of these buildings.

Can condo projects still be financed?

If homeowners still want the security of owning a condo, instead of renting (since Ontario has no rent control for new purpose-built rental buildings), but the pre-sales model is no longer workable, how do condo projects get financed? You need to pay up front for the workers and the materials to build the building, and that means you need lenders.

To finance a condo building without pre-sales, you would need lenders who are willing to fund the whole project, minus whatever the developer puts up themselves, similarly to the way a purpose-built rental project is financed. (One option would be to aim for flexibility: when the building is completed, plan to either run the entire building as a purpose-built rental, or sell individual apartments, depending on market conditions.)

BC has an interesting model: they offer a long-term loan to help finance a project, and in return, the developer sells the homes at 40% off. When the buyer sells the home, some time down the road, they have to repay the government 40% of whatever they sell it for.

The developer is able to build and sell homes faster - there's a lot more buyers at 40% off.

The buyer is able to own, while giving up 40% of future gains. (On the upside: if they have to sell at a loss, they only bear 60% of the loss.)

The government gets paid back when the home is sold.

What happens to the unsold condos?

What happens to the growing inventory of unsold condos? Lowering costs (like development charges), which set a floor on prices, will help future projects, but it doesn’t help past projects.

The reason the condos are unsold is that the market-clearing price has dropped below the floor set by the cost to build them. Just as a price ceiling results in shortages, a price floor results in surpluses.

Basically, the sellers are facing heavy losses. Sooner or later, they’re going to need to sell. From the perspective of society as a whole, the eventual fire sales at discounted prices are a benefit. The main cost to society is if developer bankruptcies reduce the capacity of the industry to build future projects.

Mike Moffatt has been arguing for expanding the GST/HST rebate to all new owner-occupied homes. This would soften the blow for developers, while helping to turn more empty condos into owner-occupied homes.

I think the other priority has to be pushing hard for viability of new projects - likely purpose-built rental - so that developers can use the profits from new projects to offset their losses as they sell off the existing inventory.

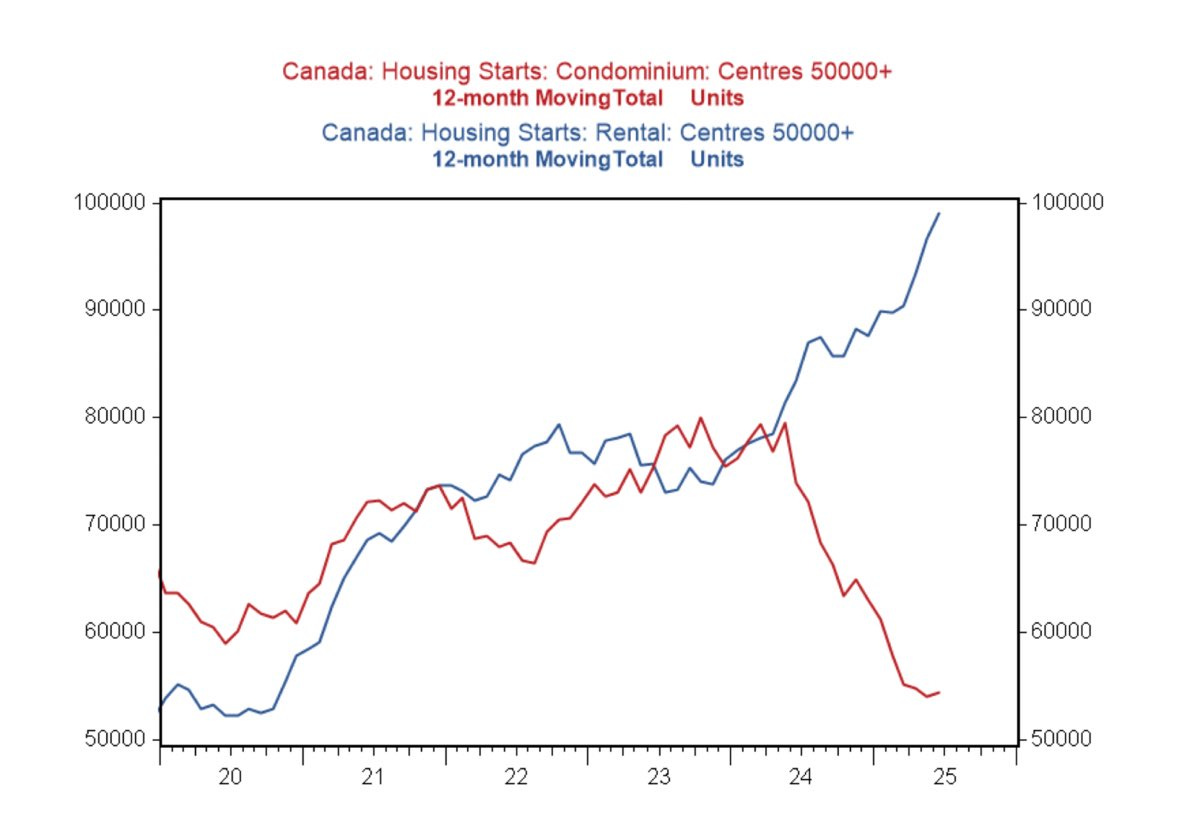

A graph from BMO, via Steve Saretsky:

From Ali Amad’s article in Maclean’s:

Even the reduced prices developers are now advertising remain out of reach for many. So sales continue to fall: this past June, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation indicated that condo sales in Toronto and Vancouver were down 75 per cent and 37 per cent, respectively, between 2022 and the first quarter of 2025.

Faced with a lack of buyers, and as many as 30 per cent of their units unsold, some developers are now converting entire projects into rental buildings. Taking advantage of their urgency to offload inventory, opportunistic investors are also stepping in to buy large blocks of units at discounted prices.

More

This condo investor is being sued for $860,000 for failing to close. He’s one of dozens facing lawsuits as default rates soar. May Warren and Clarrie Feinstein, the Star, April 2025. An earlier article on Nizar Tajdin and investors like him.

Unsold condos, August 2024

If land values are a residual, determined after all the costs (now higher than ever) and revenues (seems to have hit a ceiling) of development, then should we start to see site acquisition prices decline to the point where projects begin to be viable again? Or are land prices sticky and in a sense only partly residual?

On pre-sales, interesting point here (https://gellersworldtravel.blogspot.com/2025/08/cbc-early-edition-ways-to-advance.html) suggesting that banks used to do more conventional underwriting for condo development financing, but then pre-sales emerged as a marketing strategy and once banks saw that play out successfully their underwriting changed to increasingly rely on pre-sales. Not sure how to change that dynamic.

Silly people who entered into presales but have no ability to close at the outset really earned their misfortune.