A Reddit thread from a couple months back.

Someone commented:

"Homeowners like high prices" is exactly it. This is why whenever politicians talk about the "housing crisis" they'll never actually say "house prices are too high".

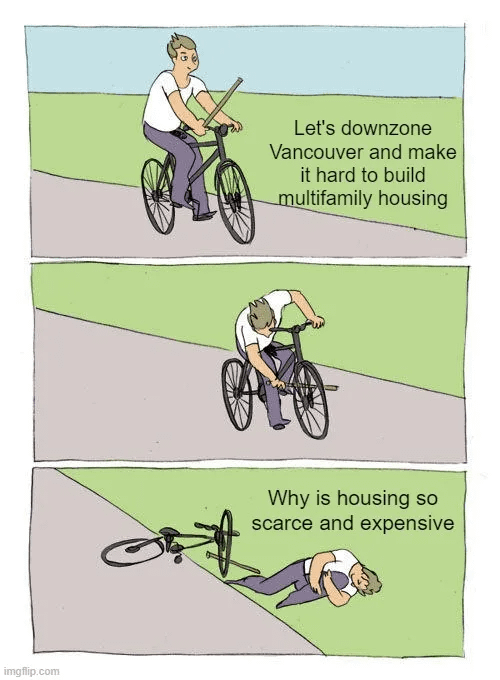

I ran for city council, which I guess makes me a politician. I'll say it: home prices are too high. CMHC has an analysis showing that there's a huge gap between the hard costs of building an additional apartment and the selling price in Vancouver. (This gap doesn't exist in Montreal, which has much lighter regulation and development charges.) If we can eliminate this gap, that would reduce prices and rents for apartments by roughly 1/3.

Housing in Vancouver is scarce and expensive because we regulate new housing like a nuclear power plant, and we tax it like a gold mine. And then post-Covid, the housing shortage in Vancouver has spilled over to the rest of BC and to Alberta.

What happened in the 1970s:

Homeowners fear change to their neighbourhood, not falling prices

Someone else commented:

I'm curious - isn't this precisely the type of minority policy position that's likely precluding you from being elected to council in the first place?

So my theory is that homeowners don't actually care that much about maximizing their property values. In fact, a few years ago when I was talking to other parents whose kids were in high school, it was common to hear people say that things were insane. Where are our kids supposed to live?

I always try to appeal to people's self-interests, not their altruism. If I'm talking to older homeowners who are insulated from the housing market and don't see why we should build more housing, I point out that when younger people can't afford to live in Metro Vancouver, hospitals are going to have a very hard time hiring and retaining nurses, and even doctors. Where are they going to live?

I describe what we need as the "next level up": townhouses or small apartment buildings in residential neighbourhoods, high-rises near SkyTrain stations and city centres, low-rise and mid-rise apartment buildings near shopping areas.

Why would people not care about the value of their most important asset? Two reasons. One is that nobody believes that home prices will fall. Why would they fear something that they don't think will happen?

The other reason is that a higher home price doesn't actually benefit them that much unless they're willing to sell and move, and then where would they go? Glaeser and Gyourko, 2018:

Housing wealth is different from other forms of wealth because rising prices both increase the financial value of an asset and the cost of living. An infinitely lived homeowner who has no intention of moving and is not credit-constrained would be no better off if her home doubled in value and no worse off if her home value declined. The asset value increase exactly offsets the rising cost of living (Sinai and Souleles 2005). This logic explains why home-rich New Yorkers or Parisians may not feel privileged: if they want to continue living in their homes, sky-high housing values do them little good.

Finally, although I would expect that we can build more apartments and reduce their prices, we're not going to be able to reduce the price of land. So for somebody who bought a detached house 20 years ago (now worth more than a million dollars), most of that is going to be the land. Auckland upzoned in 2016, allowing more housing on most of the land in the city. The result is that apartments are cheaper (because there's more of them), but detached houses ("villas") have kept their value or increased (because the land can be redeveloped for higher density). Densification helps first-time homebuyers without hurting long-time homeowners - assuming that what the homeowners have is a house rather than a condo.

They responded:

See, this is where you would immediately lose me as a voter, and I'm a younger millennial who doesn't own a home (I'm nowhere close).

I can go into more detail, but my overall point is that the way that you present housing in Vancouver doesn't align with how it practically operates, and more importantly, how people perceive that it does.

Fascinating. If you have time to go into more detail I'd love to hear it.

I'm thinking of a homeowner who lives in their house and doesn't have any other real estate investments. Whenever new housing is proposed, I would say that most of the opposition comes from people in this situation. They're not thinking of their property values (they have no plans to sell and move), they're thinking of their neighbourhood.

This reasoning doesn't apply to a homeowner who's also an individual investor and has purchased one or more properties for rental income and capital appreciation. I can of course see that someone in this situation would have a strong financial incentive to not want to vote for someone who promises to flood the market with condos and rentals, bringing down prices and rents.

That said, I would point out that all the lights are flashing red and all the sirens are going off. The Covid surge in people working from home and therefore needing more space has really aggravated the housing shortage (plus there's been a second demand shock, the post-Covid boom in international students, especially at Ontario colleges, although the federal government is now cutting that way back). There's people making $100,000 a year who are being pushed out of Metro Vancouver. There's people who are middle-class and homeless: a woman making $70,000 a year is couch-surfing because she can't find a place.

In other words, it's not just me. There's a tremendous amount of pressure on governments of all political stripes to build more housing, so that it's not so desperately scarce and expensive.

If you're not already a real estate investor, I would also point out that real estate has a lot of disadvantages as a way of saving and investing for retirement. Compared to investing using low-cost index funds (the Canadian Couch Potato method), it's highly leveraged (and thus risky), it's completely undiversified (ditto), and it's not scalable (you can't invest steadily over time, you have to "pull the trigger" and thus risk buying at a peak). And of course, transaction costs are extremely high. The main advantage of real estate investing is that if you're low-trust (I think of my parents), it's a tangible investment that you can touch.

Prices and rents reflect scarcity

Another response:

It seems naive to me that anyone would think a developer would charge less than the maximum value they could get for a unit or property, and the idea of simply reducing regulations and conditions would result in anything but more profit for developers and owners.

The maximum value you can get depends on how much competition there is. I always think of this comment by Zak Vescera comparing Vancouver (vacancy 1.2%) to Saskatoon (vacancy 5.7%), from November 2019:

Apartment hunting in Vancouver: 20 people at the showing. There are no windows. Lease is 600 years. Price is your soul.

Apartment hunting in Saskatoon: Utilities you never knew existed are included in rent. Landlords call you drunk at night begging you to move in.

The way I always describe it: housing is a ladder, it's all connected. When we block new housing, the people who would have lived there don't vanish into thin air, they move down the ladder and bid up prices and rents further down.

Every time a new building opens up with 100 or 200 apartments, that's 100 or 200 fewer households competing with everyone else for the existing housing. In other words, new housing frees up older housing.

To be a little more precise:

CMHC estimates that housing costs in Metro Vancouver have to rise about 2% in order to reduce demand by 1% - in other words, to force 1% of people to give up and leave.

Equivalently, if we had 1% more housing than we actually do today, housing costs would be about 2% lower. That is, the people who would move here are people who can’t afford to live here now, but who would (just) be able to afford housing costs which are 2% lower.

Similarly, if we had 10% more housing than we actually do, housing costs would be roughly 20% lower.

For a spectacular example, check out what's happening in Austin right now. There's a lag between demand and supply, so you get a boom-and-bust cycle. During Covid, a lot of jobs and a lot of people moved to Austin, resulting in rents going up. A bunch of people launched projects to build more rental housing. Now they've got oversupply, and asking rents fell 12.5% from December 2022 to December 2023.

Noah Kagan (one of the first employees at Facebook) reported in November that he lost a $100,000 investment with a real estate syndicate in Austin. The syndicate provided an explanation which seems reasonably clear: interest rates are up, so they need to pay more in interest every month, and there’s a lot more supply on the way.

Several factors have led to financial challenges in the multifamily real estate market and this specific asset. The reality is that we acquired this property in December 2021 at the peak of the market, and since then, multifamily fundamentals have deteriorated rapidly. In December 2021, SOFR was 0.05%, Austin market occupancy stood at 93%, and this asset was bought at a 3.4% cap rate. Since then, SOFR has risen to 5.32%, Austin market occupancy has dropped to 88% with a 20-30% increase in supply coming available leading to the lowest Austin market occupancy of all time. Multifamily cap rates have expanded to a 6% cap rate. Even if the market stabilizes at a 5% cap, we must increase NOI by 50% to get back to breakeven. NOI ultimately cannot cover both debt service increasing from $171k per month to $340k per month, and increased operating expenses.

Recent BOVs have valued the asset at $160k/door, and the debt is $200k/door. It is not worth the debt. Given these circumstances, it is not financially viable to continue. We greatly appreciate investors’ contribution to the capital call in March 2023. However, considering the current market conditions, it would be imprudent to utilize the remaining funds. Our goal is to return as much capital as possible to investors who participated in the capital call.

The GVA Team has worked diligently to find a viable path forward, including multiple attempts with LoanCore to restructure the loan. Unfortunately, this has been unsuccessful, and LoanCore has requested receivership by January 2, 2024 leading to a foreclosure.

Allowing buildings to be taller

Another comment:

I don't think "increasing supply" is going to lead to the 80% reduction in house prices we'd need to make housing affordable.

The floor for condo prices and apartment rents is determined by the cost of building a new apartment. If it costs $500,000 to build an additional apartment (assuming you've already paid for the land), and if we can freely build them, then that sets a ceiling for the price of existing condos of $500,000. To own, this requires a household income of about $160,000 (3X household income). Or for a rental, with a 4% rate of return, that translates to a rent of $1700/month.

If we can bring down that cost to $300,000, that translates into a household income of $100,000 to own, or a rent of $1000/month.

I know people don't necessarily like high-rises. (What about the view cones?!) And they take a long time to plan and build; low-rise projects are a lot faster. But the advantage of high-rises is that the fixed costs of the project can be spread over a very large number of apartments. Where land costs are particularly high - close to city centres with lots of jobs, or close to SkyTrain stations - it makes sense to allow a lot of height.

Edward Glaeser, How Skyscapers Can Save the City, 2011:

Building up is more costly, especially when elevators start getting involved. And erecting a skyscraper in New York City involves additional costs (site preparation, legal fees, a fancy architect) that can push the price even higher. But many of these are fixed costs that don’t increase with the height of the building. In fact, once you’ve reached the seventh floor or so, building up has its own economic logic, since those fixed costs can be spread over more apartments. Just as the cost of a big factory can be covered by a sufficiently large production run, the cost of site preparation and a hotshot architect can be covered by building up.

The actual marginal cost of adding an extra square foot of living space at the top of a skyscraper in New York is typically less than $400. Prices do rise substantially in ultra-tall buildings—say, over 50 stories—but for ordinary skyscrapers, it doesn’t cost more than $500,000 to put up a nice 1,200-square-foot apartment. The land costs something, but in a 40-story building with one 1,200-square-foot unit per floor, each unit is using only 30 square feet of Manhattan—less than a thousandth of an acre. At those heights, the land costs become pretty small. If there were no restrictions on new construction, then prices would eventually come down to somewhere near construction costs, about $500,000 for a new apartment. That’s a lot more than the $210,000 that it costs to put up a 2,500-square-foot house in Houston—but a lot less than the $1 million or more that such an apartment often costs in Manhattan.

More

A conversation with Justin Trudeau on Canada’s housing crisis. Irene Galea, Globe and Mail’s City Space podcast, May 23, 2024. Galea asked if homeowners needed to accept lower prices; Trudeau’s response was that they shouldn’t expect prices to keep rising on their past trajectory, but it sounded like he expected them to remain stable rather than declining. As the Globe pointed out, this sounds like it contradicts the overall push to make housing less scarce and expensive for younger homebuyers. One way to reconcile this apparent contradiction is to separate the cost of land (which is limited) from the cost of floor space (which should be much more abundant). What we want is to build a lot more floor space, making it cheaper; but low-density housing should retain its value, since it’s mostly land.

Does solving B.C.'s housing crisis mean home values need to come down? Premier weighs in. Robert Buffam, CTV News, June 14, 2024. “Asked flat out Thursday by CTV News whether he wants house prices to go down, David Eby indicated he did – while maintaining there would be opportunities for homeowners to make a profit under new rules allowing for multiple units on single lots. ‘I hope for a soft landing, a gentle landing in housing prices in the market,’ the premier responded.”

Homeowners fear change to their neighbourhood, not falling prices.