Cutting property taxes while Vancouver's community centres are falling apart

Why Ken Sim's "zero means zero" is a terrible idea

It takes work to make things last

Real assets, like buildings, roads, and pipes, wear out over time. They require constant repair and maintenance to keep them running.

Noah Smith, writing in July 2024: There’s not that much wealth in the world.

Understanding wealth as real productive assets, instead of numbers on paper, helps us to understand the impermanence of the world we’ve built. The walls and institutions that surround you look like they’re built to last forever. But they aren’t. Without constant maintenance and replacement — constant human effort — they will crumble very quickly.

This is why I think income is fundamentally more important than wealth. The modern industrialized world is not something that we built in the past — it’s something we build and rebuild every day with the sweat of our labor. The amount of value we accumulate is much less than the amount of value we produce.

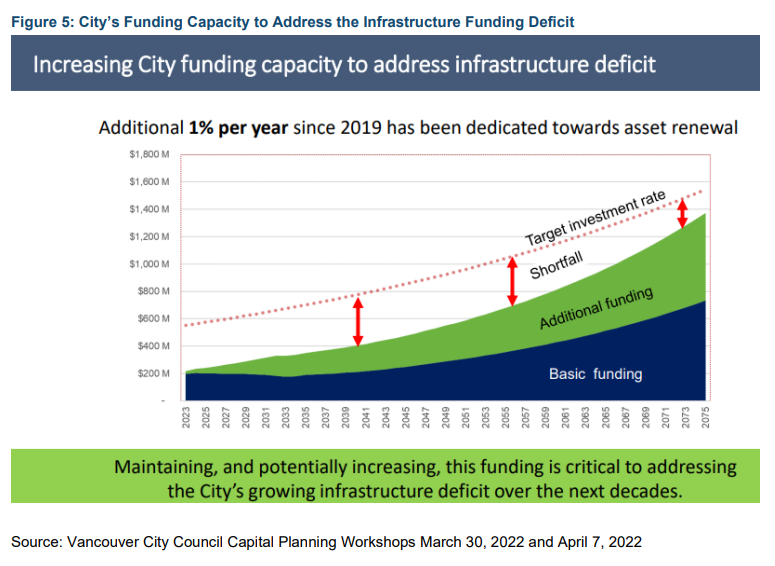

The city of Vancouver has physical assets with a total replacement cost of $34B: underground pipes carrying clean water and wastewater, roads and sidewalks, community centres and parks. The city’s estimate is that we need to spend about $800M annually, about 2.5%, to keep all of these assets in a state of good repair.

What we’re actually spending is about $300M annually1, so that we can keep property taxes low. Low property taxes, like low interest rates, inflate prices, because it makes Vancouver real estate more attractive to investors. It lowers their carrying costs.

Sarah Grochowski, writing in the Vancouver Sun, describes the state of the Vancouver Aquatic Centre, built in 1974. Majority of Vancouver rec centres, pools and rinks in ‘poor’ condition with no funding plan: audit.

In 2019, the park board’s VanSplash report had said the centre “was reaching the end of its functional lifespan.” In 2022, a section of the exterior wall collapsed above the entrance doors, and in 2024, a piece of concrete fell from the ceiling. Originally estimated to cost $94 million for replacement, the city has since allocated $140 million for a phased renewal.

A growing city needs amenities as well as housing

As Vancouver grows, we need amenities like community centres and libraries. They’re particularly important for families with children. For children and teenagers, they’re complementary to schools, providing recreational activities when they’re not in school.

Someone asked on Reddit: why does the city need to pay for community centres at all?

I don’t really understand the point of the city running pools, ice rinks etc. If there is demand for these things then they should be able to run as normal businesses and pay for themselves.

Joseph Heath describes taxation and public spending as a form of collective shopping. For some goods (food, clothing) it makes no sense to buy them collectively. For others (roads, insurance) it does make sense. From Filthy Lucre (2009):

So if Canadians want to consume more health care or a new subway or better roads, what are their options? The situation is the same as with condo residents who want a new sauna: If people want to buy more of this stuff (and are willing to buy less of something else), then they should vote to raise taxes and buy more of it. It doesn’t necessarily impose a drag on the economy to raise taxes in this way, any more than it imposes a drag on the economy when the residents of a condo association vote to increase their condo fees.

One can see, then, the absurdity of the view that taxes are intrinsically bad, or that lower taxes are necessarily preferable to higher taxes. The absolute level of taxation is unimportant; what matters is how much individuals want to purchase through the public sector (the “club of everyone”), and how much value the government is able to deliver. This is why low-tax jurisdictions are not necessarily more “competitive” than high-tax jurisdictions (any more than low-fee condominiums are necessarily more attractive places to live than high-fee condominiums).

Furthermore, the government does not “consume” the money collected in taxes - this is a fundamental fallacy; it is merely the vehicle through which we organize our spending. In this respect, taxation is basically a form of collective shopping. Needless to say, how much shopping we do collectively, and in what size of groups, is a matter of fundamental indifference from the standpoint of economic prosperity.

Auditor: the city doesn’t have a capital asset framework

The province requires that stratas (like the townhouse complex that my family lives in) have a regular “depreciation report.” We need to know when things like the roofs or the parking membrane will reach the end of their expected life, meaning that we’ll have a large capital expense to replace it.

From the province’s website:

Depreciation reports must include a financial forecasting section to help the strata corporation, and owners, to plan for the repair and maintenance of common property and assets.

The financial forecasting section must include:

The anticipated maintenance, repair and replacement cost for contingency reserve fund common expenses (expenses that usually occur less often than once a year or do not usually occur) projected over 30 years and the factors and assumptions used, including interest and inflation rates.

At least 3 cash-flow funding models for the contingency reserve fund over 30 years. Cash flow models could include: the contingency reserve fund, special levies, increased strata fees, borrowing or some combination of these.

In September, the city’s auditor general released a report2 on Vancouver’s pools, community centres, and rinks, which have a replacement cost of about $2.1B - a small part of the city’s $34B in capital assets. The report found that most of these facilities - about 72% - were in “poor” or “very poor” condition.

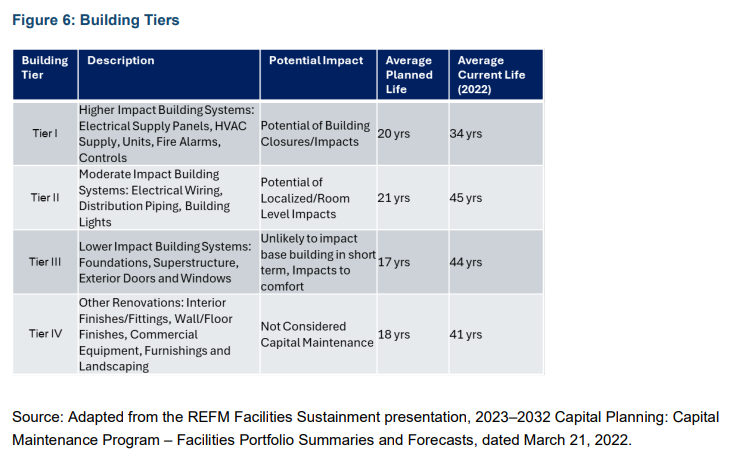

The auditor general reports that the city doesn’t have a capital asset management framework, and hasn’t been setting aside money to replace facilities as they reach the end of their useful life. The city is just keeping old building systems running instead of replacing them. Often these systems have been running for more than twice as long as they were designed for. They should have been replaced long ago.

It’s like we’ve been putting off replacing a very old roof because we don’t have the money, crossing our fingers, and hoping that it doesn’t leak.

What this looks like

The auditor-general’s report describes an issue with the Kerrisdale and Britannia rinks:

Kerrisdale Rink, a historic facility with over 75 years of service, remains one of Vancouver’s oldest operational ice rinks. In March 2024, a brine pipe leak beneath the ice surface caused soft spots, raising safety concerns. A temporary repair was completed, but it only offered short-term mitigation.

That same month, a similar brine leak was identified at Britannia Rink, another aging facility in the city. The rink floor was 50 years old at the time of the leak, exceeding its expected lifespan of 30 years. A provisional fix was applied, but as with Kerrisdale, the repair was not a long-term solution.

Though a planned repair was subsequently scheduled for Britannia, concerns were expressed that the Kerrisdale leak may recur, and another unplanned repair may be required before a longer-term solution is implemented. If not fully addressed, recurring issues could impact the rink’s ability to deliver planned recreational programs, reduce available ice time, and compromise service levels.

These simultaneous issues highlighted systemic risks in Vancouver’s aging recreational infrastructure, where deferred maintenance and outdated systems increase the likelihood of operational disruptions.

What needs to happen

Vancouver’s an expensive city. Everyone feels stretched to the limit. It’s natural that municipal elected officials are reluctant to raise property taxes.

But the money to maintain our community centres, our roads and sidewalks, and our water and sewer pipes, so they don’t age and fall apart - let alone improving them - needs to be paid.

The bills are coming due. We need to figure out how much we owe: how much is it going to take to get our community centres, and the other $32B of assets that the city maintains, back into a state of good repair? And what’s our plan to pay those bills?

The fact that investors own a lot of Vancouver real estate means that if we need to raise property taxes, they’ll be paying a lot of the bill.

Given this situation, Ken Sim’s “zero means zero” seems like a terrible plan. Prudent management means making sure that the city’s property-tax revenue is enough to cover the operational and capital spending that we need to provide decent services, while saving up enough to replace buildings, roads, and pipes as they wear out. If some of the work that city staff are doing is low-priority, like micromanaging new housing (edible landscaping!), then we should identify that low-priority work and stop doing it.

Instead, he’s basically trying to get enough staff to quit to reduce the city’s total wage bill. Not the ones doing the lowest-priority work - just whoever’s willing to quit and look for another job.

The result:

The city’s finances will be even more underfunded. Inflation means that a zero-percent increase translates to a real cut.

We’ll lose the people who are in the best position to be able to find a new job.

The workload remains the same, but with fewer people to do it.

This translates to worse services (like new housing taking even longer to get approval), and more community centres, roads, and pipes wearing out and falling apart.

This sounds more like Detroit, which suffers from declining jobs, low demand, and a shrinking population, than Vancouver.

We’re a high-demand city: lots of people want to live and work here. Why are we not planning for growth?

More

Vancouver council’s property tax freeze motion leaves more questions than answers. Justin McElroy, CBC News, October 2025.

‘Layoffs in disguise?’ Vancouver’s back-to-office mandate spurs debate. Dan Fumano, Vancouver Sun, October 2025.

Decades-long repair waits: 11 community centres in Vancouver in poor condition. Kenneth Chan, Daily Hive, April 2022.

Sarah Kirby-Yung calls for fewer studies, more realistic and timely shovel-ready projects in next capital plan. Kenneth Chan, Daily Hive, September 2025. Looks like an attempt to prioritize projects, but within a grossly inadequate capital budget.

Audit of Recreation Facility Asset Management, September 2025.

Great explanation. I feel like I’ve been waiting a long time for a succinct approachable analysis like this.

Those are great point made in the article. In response to Chipper Domez, the people contributing to the community and the workforce don't necessarily have the most money...rather they are supporting the REIT's and rental property owners. It makes sense to charge these investors and keep Vancouver a great city rather than making it a Detroit.