The downside of low property taxes

Not enough money for infrastructure, more speculative demand

If you’re a homeowner in Vancouver and your property value goes up, it’s natural to assume that your property taxes will also go up, just as income tax goes up when your income goes up.

In fact that’s not what happens - it’s more indirect. Your share of property tax is based on how your property value compares to the total of all property values. Roughly speaking, if your property is worth $1M and the total value of all property in the city is $1 trillion (= one million times $1M), then you pay one millionth of the total property tax. If your property value doubles to $2M, but everyone else’s also doubles, then you still pay one millionth of the total property tax.

The usual guideline is that when budgeting for property taxes, it’s about 1% of the purchase price. Property taxes in Vancouver are quite low, at less than 0.3%, in part because the city maximizes revenue from development charges on new housing.

We were having a discussion of property taxes on the BC Urbanism Discord server, specifically whether instead of paying for infrastructure upgrades through high development charges, it would make sense to instead issue municipal bonds and pay them back over time through property taxes (this is Montreal’s approach).

Raising property taxes is politically very difficult. But keeping property taxes low has two significant disadvantages.

It requires high development charges on new housing. This reduces supply, making renters and first-time homebuyers poorer, and constraining the size of Vancouver's economy.

It also makes Vancouver real estate extremely attractive as an investment, because the carrying cost is low. This increases demand for real estate, aggravating scarcity (demand minus supply) because supply is so inelastic.

Maybe it’s just that property values are high?

You sometimes run into the argument that Vancouver’s property taxes aren’t really low, it’s just that property values are unusually high.

If we look at property taxes on the median home in Burlington, Ontario vs. on the median home in Vancouver, to take price differences out of the equation, in Burlington you'd pay $6300 annually (on a $780,000 home), while in Vancouver you'd pay $3900 (on a $1.4 million home). Nothing against Burlington, but I think most people would rather live in Vancouver, and I think the average homeowner in Vancouver is probably higher-income than in Burlington.

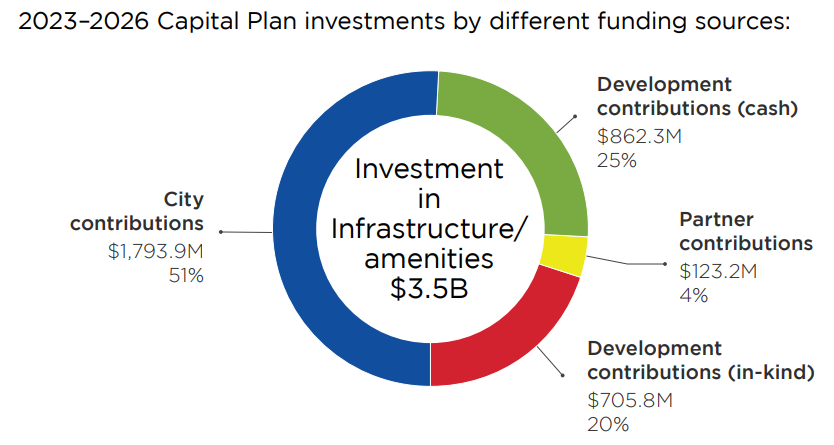

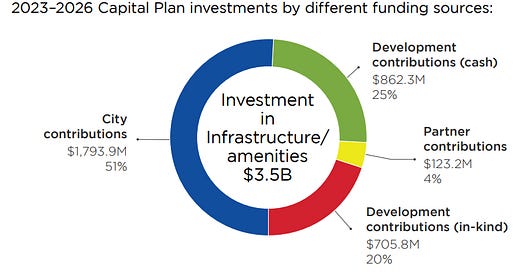

There isn’t enough funding going into infrastructure. From the 2023-2026 capital plan:

Building on the 2019-2022 Capital Plan, increasing the City’s capacity to address its growing portfolio of aging infrastructure and amenities in a financially sustainable and resilient manner continues to be the core theme of the City’s mid to long-term capital planning framework. Based on an estimated replacement value of $34 billion, we need to invest ~$800 million annually to maintain our assets in a state of good repair.

The actual plan is to spend about $500 million annually on maintenance and renewal. That’s a very large deficit. For an example of what this means, see this Daily Hive story from April 2022. Decades-long repair waits: 11 community centres in Vancouver in poor condition.

Why is raising property taxes difficult?

Short answer: loss aversion. Having your real income go down is quite painful.

Joseph Heath, describing the utopian nature of “degrowth” proposals to reduce people’s real incomes while also redistributing income on a much larger scale, and expecting people to repeatedly vote for this:

What I find astonishing about proponents of “degrowth” – not just [Naomi] Klein, but Peter Victor as well – is that they don’t see the tension between this desire to reduce average income and the desire to reduce economic inequality. They expect people to support increased redistribution [increasing income-tax rates from 30% to 55%] at the same time that their own incomes are declining [by around 20%]. This leaves me at something of a loss – I struggle to find words to express the depth of my incredulity at this proposition. In what world has this, or could this, ever occur?

In the real world, economic recessions are rather strongly associated with a significant increase in the nastiness of politics. Economic growth, on the other hand, makes redistribution much easier, simply because the transfers do not show up as absolute losses to individuals who are financing them, but rather as foregone gains, which are much more abstract. It’s not an accident that the welfare state was created in the context of a growing economy. (See Benjamin Friedman, The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth, for a general discussion of the effect of growth on politics.) It seems to me obvious that a degrowth strategy – by making the economy negative-sum – would massively increase resistance to both taxation and redistribution. At the limit, it could generate dangerous blow-back, in the form of increased support for radical right-wing parties.

In short, it’s easier to raise taxes - including property taxes - when the economy is growing and people’s real incomes are rising. Their incomes are still higher than before, just not as high as they would have been without the tax increases.

When people’s real incomes are declining, it’s much more painful to accept higher taxes.

Land value tax: taxing land more heavily than buildings

One idea that often comes up is a land value tax, taxing property primarily on the value of the land and not the buildings. Shifting the tax burden to land and away from buildings provides a stronger incentive to build (since taxes are lower and the rate of return is higher), and to sell vacant land instead of speculating on future increases.

In fact Vancouver used to have a land value tax. Christopher England, Land Value Taxation in Vancouver: Rent-Seeking and the Tax Revolt (2018). Over time, as home ownership increased, there was political pressure to shift the tax burden from single-detached homes to apartment buildings, from homeowners to renters. Buildings were initially taxed at zero (from 1910 to 1918), then 50% of the rate on land (1919 to 1969), then 75% (1969 to 1984), and finally 100% (after 1984). Via Reddit.

In 2018, Vancouver city council passed a motion asking city staff to investigate bringing back a land value tax. They recommended against it: staff report.

Thomas Davidoff: raise property tax, cut income tax?

So I got here from California, and California is a low property tax environment. I opened up my property tax bill, saw the number, and I said, “Oh that must be for the month.”

That was my annual bill. Then I paid my income taxes, and I said, “Ah – that’s how everything is funded.” Very high income taxes if you’re a high earner, very low property tax rates.

Interview with Stuart McNish, 2018.

Policy Forum: Vancouver's Property Taxes in Perspective, Canadian Tax Journal, 2018. “A natural comparative measure of the property tax burden across markets is the ratio of property tax to rent. By this measure, the total property tax burden for a typical owner-occupied home in Vancouver (10 percent) is significantly lower than the mean among other Canadian cities (16 percent).”

UBC professor proposes innovative property tax system to help housing affordability. Vancouver Is Awesome, 2018. “By raising property taxes and lowering income and sales taxes, you could have a more dynamic economy. People recognize that unaffordability is currently hindering the economy, due to how hard it is to draw workers here to Vancouver who can’t be comfortably housed. But lowering income and sales taxes will also bolster the economy, because people will have more money to spend and more incentive to work and do business.”

As Davidoff notes, it’s hard to see how this would happen: for homeowners who are retired, or close to retirement, they would be paying higher property taxes, while not benefiting significantly from income-tax cuts unless they’re particularly affluent.

Other ways that property taxes are kept low

Because homeowners are more likely to vote, there’s a lot of pressure to reduce property taxes on homeowners.

Property tax rates on commercial property are higher than on residential property.

There’s an annual $570 grant for owner-occupied housing worth up to $2M. The annual cost is $800M. The Green Report: “Our conclusion is that this is a costly program that does not target any group clearly in need or achieve any evident public policy objective.”

Also see "How low taxes lead to high home prices in Vancouver, BC." Danny Oleksiuk, Sightline, 2022. https://www.sightline.org/2022/05/09/how-low-taxes-lead-to-high-home-prices-in-vancouver-bc/

It's a shame that in that report by the city staff, they apparently didn't consider the most straightforward and low-hanging fruit proposal: to simply shift taxes slightly away from structures and onto land like how things used to be. The taxes changes over the last century ridding us of LVT changed the rate on land from 0% to 50% to 75% to 100%. We could start by taking one step in reverse, going down to 75%.

Was this an oversight that this wasn't considered in the report? Or was this not considered on purpose so as to make change seem like a bad idea? Maybe my tinfoil hat is restricting blood flow, but it strikes me as very similar to how the Liberals sunk electoral reform.