Evan Siddall on the dangers of high home prices, pre-Covid

"Trees don't grow to the sky"

Too Much of a Good Thing: On Housing, Wealth and Intergenerational Inequity. Evan Siddall, April 2018.

Evan Siddall was head of CMHC from 2014 to 2021. In this speech, given in Halifax, he talked about the dangers of high home prices.

Unrealistic expectations:

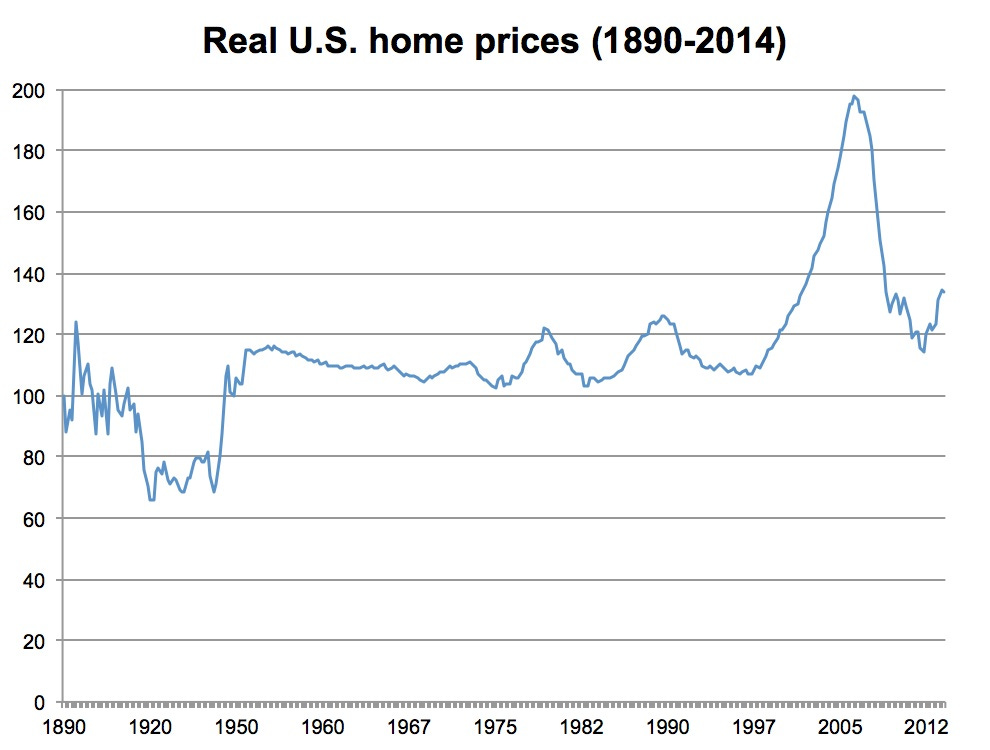

It is a law of investing that past results are poor predictors of the future. Yet, many Canadians believe house prices don’t fall and use that belief as a financial planning assumption. We asked people who had just bought a home in Montréal, Toronto or Vancouver if they thought real estate was the best long-term investment. More than three quarters of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed. People believe trees grow to the sky. Only half agreed or strongly agreed that financial investments – stocks and bonds – were the best option in the long term.

We know that many homebuyers make decisions to purchase or sell a house with an eye to the future. In short, they are willing to pay more for housing today in anticipation of price gains tomorrow. The more optimistic they are, the more they are willing to bid up prices. Excessive optimism about the future of house prices can lead to speculative investment and bidding wars, both of which further drive price escalation.

Increasing debt and inequality:

As I have noted elsewhere, most urban Canadians support the concept of densification – as long as it is happening in someone else’s neighbourhood. But it can’t always happen somewhere else. It needs to happen in every community where housing markets are imbalanced due to a lack of supply, or where urban sprawl is impacting our environment and quality of life.

The alternative to densification is far more worrisome than whether the character of a neighbourhood may change a bit. Continued escalation of house prices in Canada will lead only to higher household debt, reduced housing affordability in both homeownership and rental markets, unsustainable urban growth and rising wealth inequality – an even greater gap between the rich and the poor in this country.

Risks to economic growth and stability:

As house prices rise, those who are not readily able to borrow to increase consumer spending – perhaps because of poor credit – may instead withdraw equity from their home by incurring debt, for example through a line of credit or second mortgage. This group is also more likely to reduce consumption if house prices drop. A study in Australia found that young people with low and medium levels of liquid wealth tend to be sensitive to home prices, as are older Australians whose net worth is largely tied up in housing. U.S. researchers also found that “young people who are more likely to be credit-constrained, and older homeowners, likely to be ‘trading down’ on their housing stock, experience the largest housing wealth effects.” Again, therefore, the young could suffer disproportionately if they become homeowners and prices subsequently fall.

The negative effect of falling house prices on consumption can last a long time, as suggested by the U.S. experience after the Great Recession. Consequently, if rising home prices create perceptions of greater wealth that eventually prove to be unfounded, the related increase in consumption will be unsustainable. The impacts on financial stability may be particularly severe if that consumption is financed by other credit. Economists Atif Mian and Amir Sufi, as well as colleagues at the IMF, have shown that high levels of indebtedness coupled with elevated house prices precede economic contractions.

The need for more supply:

Unrealistic expectations of trees in the clouds can be confronted by data on housing supply today. Improved market information can therefore help limit unwarranted price increases. If prospective homebuyers know that additional supply is on the horizon, they will be less likely to pay exorbitant prices for homes that are currently available – and in high demand – in a supply-restricted market. Moreover, purely financial investors will be discouraged by pending supply.

The post-Covid picture

Pre-Covid, comparing prices to rents in Vancouver, it was reasonable to fear that prices were over-inflated by unrealistic expectations. Post-Covid, with the sudden surge in remote work, demand for residential space has increased dramatically.

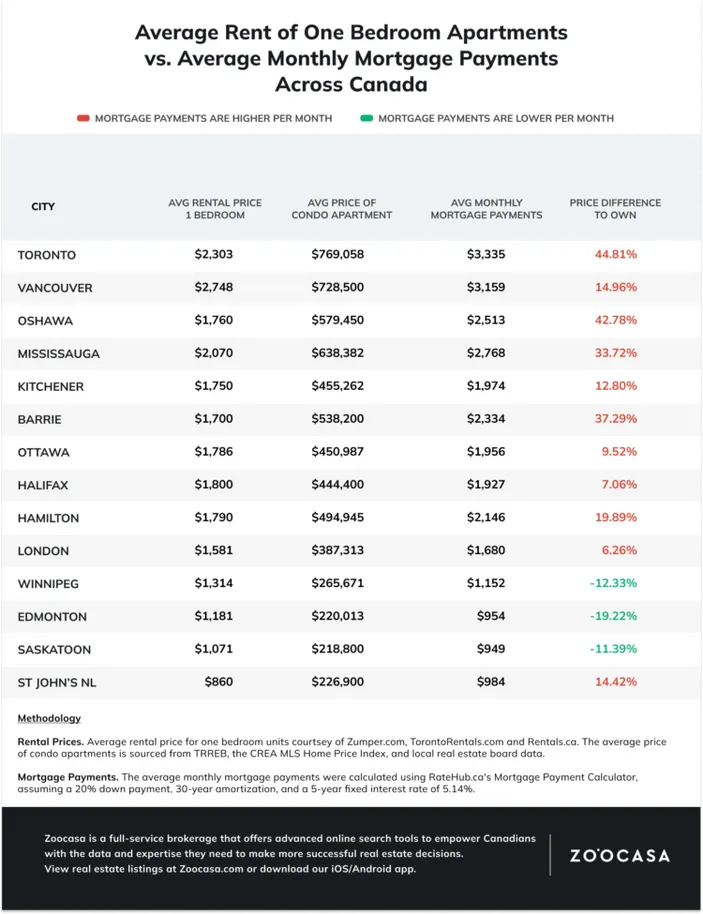

An October 2022 report from Zoocasa suggested that prices in Vancouver were only slightly overvalued, but prices in the GTA were 30-40% higher than would be reasonable. (The value of housing, whether rented out or owner-occupied, is the value of the stream of rents that you either collect or don’t have to pay.)

More

Previously: Investing in real estate is risky. Prices don’t always go up!

In August 2020, Siddall got into a Twitter fight with an over-enthusiastic realtor.

Buy a condo for $500K w 5% down: prices fall 10% and you’re forced to sell, you’ve lost your $25K d/p and still owe $25K more on your mortgage, plus the costs @owenbigland missed: $19K for mortgage insurance, $25K real estate fees, $30K interest, legal costs, land transfer taxes.

This is a very helpful article. Additional perspectives are espoused in:

https://thehub.ca/2023-10-06/the-many-economic-myths-contributing-to-canadas-housing-shortage/

https://thehub.ca/2023-10-05/vancouver-cannot-complain-about-high-home-prices-while-limiting-development-french-urbanist-says/