The city of Vancouver plans to get into market rental development

Seems like excessive risk in hopes of replacing property-tax revenue

[Update: the vote failed, 7-4, with the non-ABC councillors voting against. It required a 2/3 majority to pass, i.e. eight votes.]

From an earlier post:

Andrew Tobias’s book The Only Investment Guide You’ll Ever Need lives up to its immodest title. One of the first chapters, “Trust No One,” emphasizes an important principle: don’t invest in something you don’t understand.

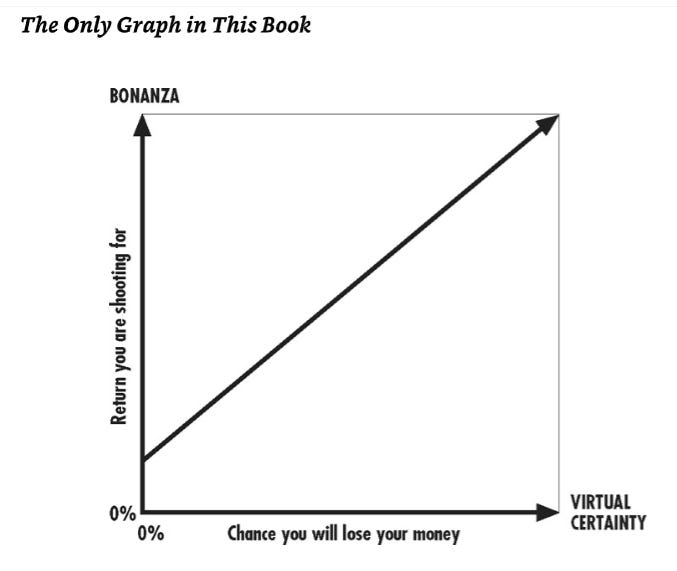

Another key principle: the higher the return you’re aiming for, the greater the risk that you’re going to lose your money.

For both these reasons, I’m wary of the city of Vancouver’s plan to become a major developer of market rentals, as a way of generating revenue. It looks to me like taking on excessive risk, as an alternative to raising property taxes. Council will make its decision today. It’ll require a vote of 2/3 of council. If I understand correctly, this means 8/11 votes, which means that the four non-ABC councillors (Pete Fry, Sean Orr, Lucy Maloney, and Rebecca Bligh) could block it.

Mike Howell, Business in Vancouver: Vancouver council asked to create ‘wholly owned B.C. business corporation.’ It’ll be called the Vancouver Lands Development Corporation.

Vancouver council will be asked Tuesday to direct staff “to take all steps required to incorporate a wholly owned B.C. business corporation” and authorize the sale of six city properties for development of more than 4,000 units of market rental housing.

The new entity would be called the Vancouver Lands Development Corporation.

The 2025 assessed value of the properties, which includes the land where the iconic 2400 Motel on Kingsway now stands, is $411.6 million, according to a report from the city’s general manager of real estate, environment and facilities management.

My understanding is that owning and operating a market rental building in Vancouver is a relatively low-risk, low-return business, comparable to putting your money into GICs. (Why not just lease the land?)

But building a rental building is a different story. It’s much riskier, and therefore has higher potential returns. But the new arms-length agency would be given some very big projects. Mike Howell quotes Brad Foster:

“The first task here is to get these sites zoned for highest and best use under market rental tenure — that’s the first task,” Brad Foster, the VHDO’s director of market rental housing, said at a May press conference. “The next task will be, ‘How do we get them built?’ And that’s where all the finance discussions will take place.”

Added Foster: “You’re definitely in the billions. You’re also in the billions in terms of financing because these are very expensive construction projects. This is the big leagues of development and we aim to not shy away from that because we have to be bold with these assets. That’s what they’re here for — to generate long-term revenue for the City of Vancouver.”

There’s six sites that’ll be transferred to the new agency. One of them is the old 2400 Motel, on Kingsway near Nanaimo. Kenneth Chan, Daily Hive: This is the City of Vancouver’s big rental housing redevelopment plan for 2400 Motel on Kingsway.

There will be 100 per cent market rental housing uses for the residential component — a total of 863 secured purpose-built market rental homes, with a unit size mix of 92 studios, 467 one-bedroom units, 214 two-bedroom units, and 90 three-bedroom units. Residents will have access to various shared indoor and outdoor amenities on all tower and base podium rooftops.

That’s a big project, with big risks.

Michael Geller: “I fear the City of Vancouver is about to make a terrible mistake”

Michael Geller wrote a long open letter to city council, and posted it to his blog.

Some key points:

Why are you selling all of the sites to the corporation? Both the UBC Properties Trust and SFU Community Trust spent considerable time exploring how best to vest their new corporate entities with the lands. Neither did what you’re being asked to do. Instead we came up with a much wiser approach which ensured that the parent entity maintained sufficient control while making the lands available when needed. Did any of you discuss the various options?

I doubt anyone at the city has even explored the best way to do this because if you had Council would not be approving a sale of all the lands.. You should not be selling all of the land worth hundreds of millions of dollars to this corporation at this time. You don’t need to.

Conflict of Interest. There is so much more I would like to discuss but I will finish off with two points. The first is whether there’s validity to my concern that the city should not be competing directly with the private sector when it comes to building market rental housing. This is something that was discussed extensively by all of the public entities referenced above and it was agreed that there is often too much potential for conflict of interest when an entity is both the approving officer and a developer. (And please don’t tell me they are different departments! It’s the same Council!)

Especially if the city is building a rental housing project on a site near a major private sector project that is going through the approval process at the same time.

Joseph Heath and Wayne Norman on the poor record of state-owned enterprises

Stakeholder Theory, Corporate Governance and Public Management: What can the History of State-Run Enterprises Teach us in the Post-Enron era? Joseph Heath and Wayne Norman, Journal of Business Ethics, 2004.

The basic reason for this commercialization of state-owned enterprises in the 1960s and 1970s was the realization that, not only were they consistently losing money, but they were often doing a worse job of promoting the public interest, under the explicit mandate to do so, than privately owned firms were. In several countries, governments suffered an almost total loss of control. In France, state oil companies freely speculated against the national currency, refused to divert deliveries to foreign customers in times of shortage, and engaged in predatory pricing policies toward domestic customers (Feigenbaum, 1982: 109). In the United States, SOEs have been among the most vociferous opponents of enhanced pollution controls, and state-owned nuclear reactors are among the most unsafe (Stiglitz, 1996: 250).

Of course, these are rather dramatic examples. The more common problem was simply that the SOEs lost incredible amounts of money (Boardman and Vining, 1989). These losses were enough, in several cases, to cast doubt upon the ongoing solvency of the state, and to prompt currency devaluations. The reason that so much money was lost has a lot to do with a lack of accountability.

The idea that agency problems in the public sector are more acute than in the private is widely accepted. In some cases, this is due to the peculiar character of the state as an owner. For example, the public sector cannot give its managers an ownership stake in the operation that they run. The top end of the pay scale is also significantly lower than in the private sector, for a variety of reasons, and this may make it difficult for SOEs to attract or retain top managers. There is also the well-known problem of the ‘‘soft-budget constraint.’’ If the managers of a privately-owned firm cannot keep it in the black, shareholders will eventually withdraw their investment, regardless of the social consequences. Because of this, private owners are able to issue much more credible threats to their managers. Politicians, on the other hand, would never allow a major public corporation to go bankrupt, and the managers know it. Thus public-sector managers have much less fear of losing money. They sometimes intentionally run deficits in order to secure budget increases.

On the other hand…

A couple counter-arguments:

The city as super-developer. A significant part of the risk in development is regulatory and political, because we have anti-growth municipal institutions dating back to the 1970s that make it difficult to build housing. So it’s possible that the city itself would be bearing less risk, because it’d be able to elude or break through its own bottlenecks in a way that’s not available to private developers. For example, it’s not planning to include 20% below-market housing in its own projects.

Another possibility is that the experience of development will give the city a different perspective on its own bottlenecks, and the motivation to fix them. Eleanor West and Marko Garlick, Upzoning New Zealand:

But though it started in 2018 with a bang, Kiwibuild quickly fizzled. The goal was ambitious, but the government immediately butted against the same constraints as any private developer: a lack of residential land, zoned for sufficient density, serviced by sufficient infrastructure.7 As a result, it took until 2021 to build its first 1,000 homes, two years late and 15,000 homes short of what had been promised by that point. (As of June 2023, Kiwibuild had delivered a reported 1,700 homes.)

The failure of Kiwibuild gave the Labour government an entirely new perspective on housing – that of a property developer. Armed with the many recommendations of the Productivity Commission, they set out to fix these constraints. In 2019 Labour announced its intention to comprehensively reform the Resource Management Act of 1991 – tearing up the existing zoning system to design a new one.

Transit-oriented development. Transit-oriented development has been a successful model. Ben Southwood and Mike Bird, The underrated economics of land:

Ben: I have one more classic one that may be familiar to people, but I think it’s such a good one that it bears repeating, which is of course that many, many historical infrastructure expansions were funded by speculation on the land that would result, and it’s still done today in certain places.

So if you are opening a new MTR station in Hong Kong, then they most likely will have either used compulsory purchase or careful slow buying up or something to get hold of the property around the new station, which will then go loads in value and they’ll sell it off and then that money will then fund the infrastructure investment they did.And this is how Chicago’s tram network, the streetcar network expanded or how the metropolitan line expanded an incredibly resilient way and how Japanese railways build their private railways, build their new places now. But something where if you don’t think about, okay, what’s actually going on here? Then it becomes like, how can all these countries fund all this infrastructure? Where is it coming from? Well, it’s coming from land value that you can just give out to the people who live around it, or you can try and use it to fund investments that benefit.

Mike: Absolutely. And the MTR has got to be the best example of that, right? I mean the MTR is like, I would encourage everyone here who isn’t familiar with this to go and read as much of it as you can, but the MTR is borderline sort of a mall and housing company that happens to have these pipes connecting things that have trains in them underneath, right? The trains are so, such a fringe part of the actual financing of the company.

So you have this, it’s the world working as it should really, I think, and it probably is made easier. Hong Kong has all sorts of problems because of the high land price policy stuff, but it does allow for this extraordinarily cheap functioning successful public transport model.

More

City of Vancouver enters new territory, buying new $38.5-million apartment building. Dan Fumano, Vancouver Sun, July 2024.

Vancouver unveils plans to build market rental housing on city-owned land. Abigail Turner, CTV News, February 2025.

Vancouver’s plan to develop rental units is risky, say experts. Alec Lazenby, Vancouver Sun, October 2025.

Yikes!!! 1. Conflict of interest - full stop.

Oh, that’s not enough, ‘reasoning’ or logical thinking?

2. No accountability - whose skin is actually in the game? Might as well be playing Monopoly. Council could commit, by providing financial collateral (co-sign with personal real estate assets). Yeah, didn’t think so.