YIMBYtown slides

Overcoming risk aversion in BC and Canada

There’s an annual conference of pro-housing advocates called YIMBYtown. This year it’s being held in Austin, and today I’m giving a presentation as part of a panel on what’s happening in Canada.

Hello, my name is Russil Wvong. In my day job, I’m a software developer. I’m from Vancouver, which has the dubious distinction of having one of the worst housing shortages in North America. We have a very active and loosely organized pro-housing community, with the lead YIMBY organization being Abundant Housing Vancouver. There’s similar groups across the country, and we’ve now set up a coalition called More Homes Canada.

One of the things I really enjoy about the YIMBY movement is the sharing of ideas, arguments, and data across different jurisdictions and different countries. In Canada, we tend to be cautious and we don’t like going first, so we do a lot of copying. It’s always helpful to be able to point to policies that have worked somewhere else.

Since I’m going first, I’ll start with some background information on Canadian politics. Then I’ll talk about what’s happening in BC, and finally what’s happening at the federal level.

Canada’s a very urbanized country, but has relatively few large cities. If the United States resembles a rectangle, Canada is more like a line. More than half the population is in southern Ontario and Quebec. The three largest cities are Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver. Other cities include Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Ottawa, and Halifax.

At the federal level, both the Liberal and Conservative parties have traditionally been cautious and ideologically shapeless. In a country that’s about 20% French-speaking, with geographic divides on top of that, Canadian politicians have been well aware of the dangers of emphasizing social divisions and potentially breaking up the country. The Liberals are still like that, happy to steal ideas from other parties. On the right, the Conservatives became more ideological in the 1990s and early 2000s. Further to the left, there’s also the New Democratic Party or NDP, sometimes described as “Liberals in a hurry.”

Currently, we have a Liberal government at the federal level, Conservative governments in most provinces including Ontario, and NDP governments in BC and Manitoba. Provincial governments have full power to override municipal governments.

One huge difference from US politics is that in Canada, we have strong party discipline. You don’t need to win over individual legislators. Key decisions are made in cabinet, with the prime minister or provincial premier having a strong influence. Once they’ve decided, as long as the party in government has a majority, it can pass legislation quite easily. But you also need to win elections, since if the government changes hands, its successor can easily pass legislation reversing the previous changes.

Vancouver and BC

This slide shows that the cost of housing in the Vancouver metro area acts as a barrier keeping people out. In 2015, you couldn’t move here unless your household income was at least $100,000. Metro Vancouver has been suffering from an acute housing shortage for decades, spilling over to other areas in BC. Canada has no shortage of land, but people don’t move around randomly, they move where the jobs are. In Metro Vancouver we have lots of jobs, and we haven’t been building housing fast enough to keep up.

We never had a real estate crash as happened in the US in 2006-2007, perhaps because Canadians are more risk-averse.

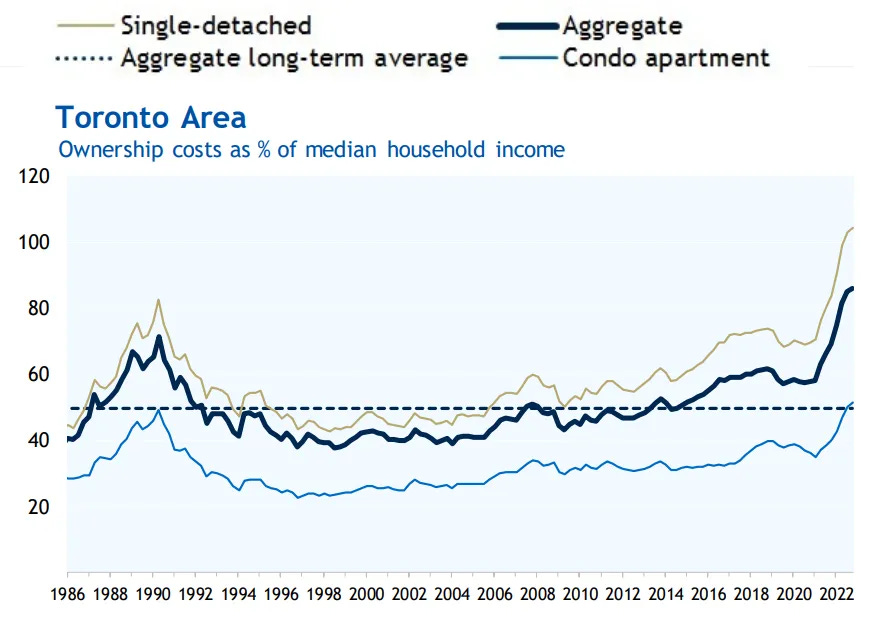

Housing in Ontario was starting to come under pressure in the 2010s, but what really lit a fire under the housing market was Covid and the sudden massive surge in people working from home and needing more space. Covid also resulted in a lot more people moving to smaller centres and driving up housing costs there. Finally, we’ve had rapid post-Covid population growth on top of that.

In Vancouver, the reasons housing is so scarce and expensive will probably sound familiar. People like things the way they are. It’s not really property values that they’re worried about, it’s the unknown effects of change to their neighbourhood, which is why opposition tends to be hyperlocal.

When making the argument for more housing, I always try to appeal to people’s self-interest rather than to altruism. Whenever I’m talking to older homeowners, I don’t talk about intergenerational unfairness. I say that if younger people can’t afford to live here, hospitals won’t be able to hire nurses and doctors, and the healthcare system will be under increasing strain.

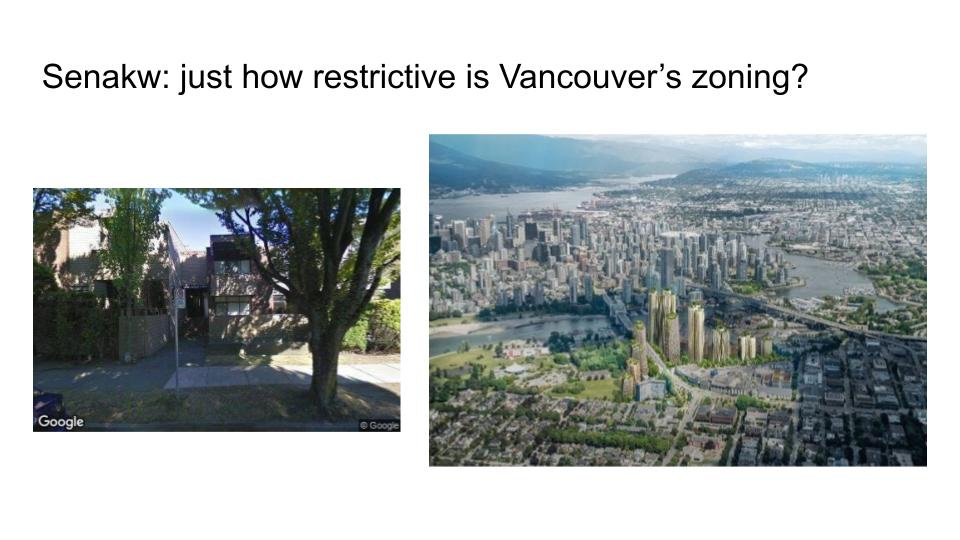

To give you an idea of just how restrictive Vancouver’s zoning is, here’s an example of an old two-storey, eight-unit rental building in a neighbourhood close to downtown. It was built in 1972. Shortly after that, the city made it illegal to build apartment buildings in the neighbourhood. So it’s illegal to replace it with a new building of the same size. Instead it’s getting replaced with three single-detached houses.

Meanwhile, literally a five-minute walk down the street, we have the Senakw project, which is putting up 6000 rental apartments on a small parcel of land, in the form of high-rises up to 59 storeys tall. This is Squamish reserve land, so it’s not subject to Vancouver’s zoning.

The good news is that the current provincial premier of BC is David Eby, of the BC NDP. He’s an impatient guy, someone who’s perfectly willing to get into fights with housing skeptics and with municipalities.

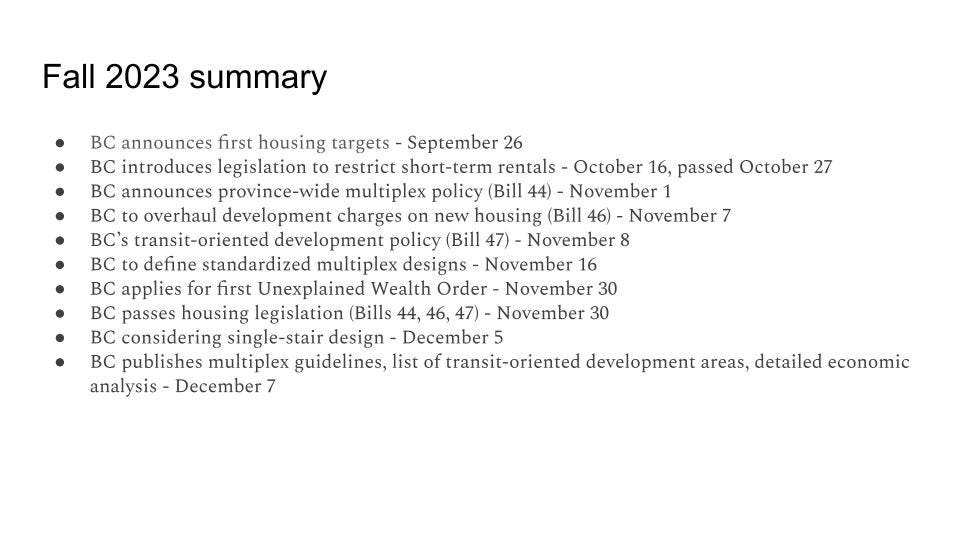

In the fall last year, the province brought in a series of legislative changes. This includes transit-oriented development, allowing more density within a 10-minute walk of rapid transit stations and major bus exchanges. But the change that’s actually expected to produce a lot more housing is an Auckland-style reform allowing multiplexes everywhere.

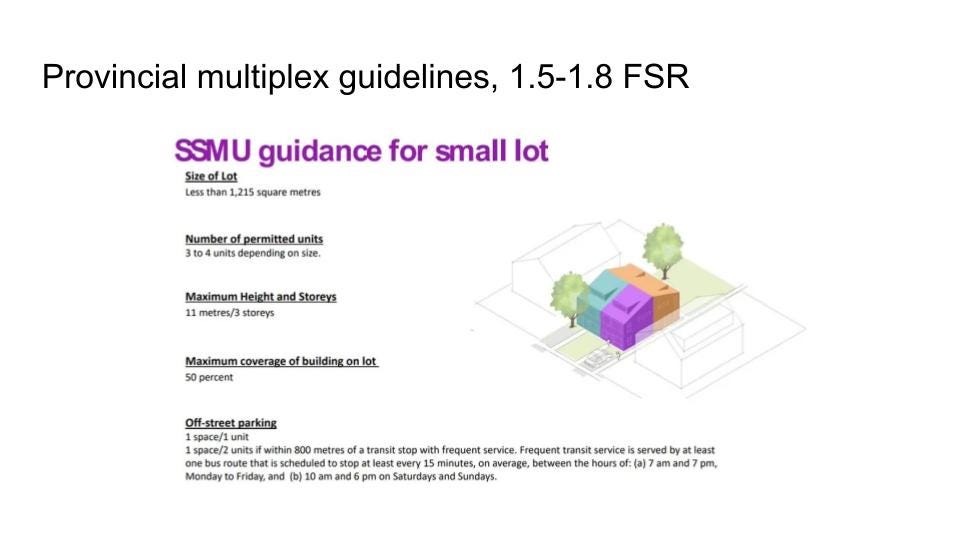

On a typical lot, you would be allowed to build a four-plex with three storeys and 50% site coverage, for a floor space ratio of 1.5. Close to frequent transit, you would be allowed a six-plex with 60% site coverage or 1.8 FSR. That's about 2-3X as much floor space as is currently allowed for a detached house. This looks pretty similar to what Auckland did. BC estimates that this will result in something like 200,000 to 300,000 additional homes over 10 years.

Low-rise projects like this are particularly important because they’re much faster to plan and build than a high-rise.

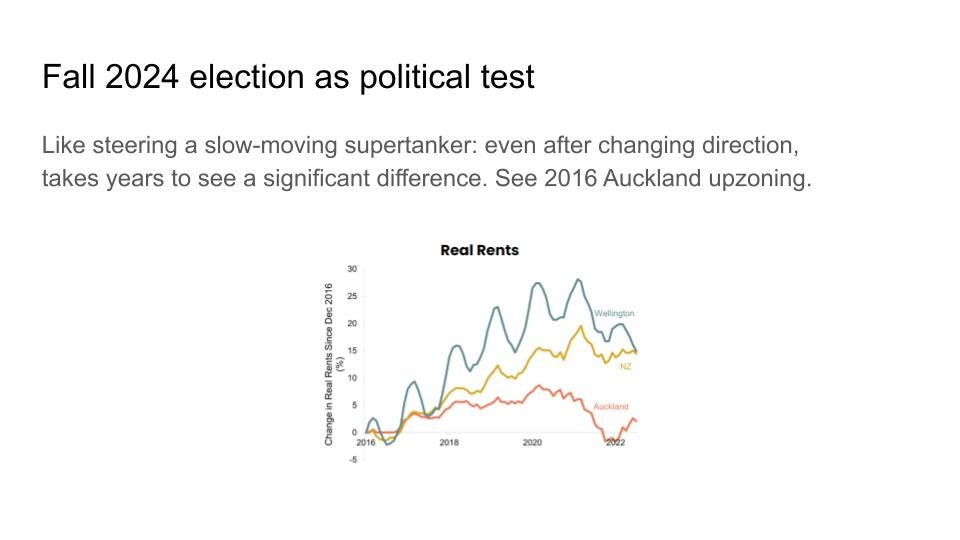

There’s a provincial election this fall, which will be a major political test for this policy. It’s like steering a slow-moving supertanker. Even after changing direction, it’ll take years to see a significant difference.

Federal politics

Turning to federal politics: Over the last eight years, Justin Trudeau and the federal Liberals have defeated three successive Conservative leaders. But post-Covid, Pierre Poilievre, the latest Conservative leader, is now way ahead in the polls. A big reason is that younger people are boiling mad about housing. Poilievre’s a small-government type. He’s perfectly happy to blame municipal gatekeepers for the shortage of housing, and to threaten to withhold federal transfers. Although recently he’s also been blaming David Eby for some reason, while ignoring the lack of action by Conservative premiers in other provinces.

For quite a while, the response of the Liberal government to Poilievre’s attacks on their housing record was to point lamely to the 2017 budget, which allocated $15 billion in new money to non-market housing. That was reasonable before Covid, when the big challenge was how to help lower-income households. But after Covid and its aftershocks, now the housing shortage is affecting younger people all the way to the top of the income scale.

Starting last September, the federal Liberals pivoted sharply on housing, with a new housing minister, Sean Fraser. Fraser’s been using a YIMBY grant program called the Housing Accelerator Fund to convince municipalities to get out of the way and allow more housing. He’s already doing what Poilievre has been talking about. As I mentioned earlier, the federal Liberals are always happy to steal ideas from other parties.

As Steve Lafleur says, Fraser has been able to figure out how to use what should be a carrot as a stick. Municipalities have been applying to the Housing Accelerator Fund, and he’s been writing letters to individual municipalities to tell them that in order for him to approve their application, they need to do specific things, like allowing four-plexes everywhere, or more height and density near frequent transit, similar to what BC is doing. For the most part, they’ve accepted these changes, in exchange for a modest one-time payment.

Besides regulating new housing like it’s a nuclear power plant, we also tax it like it’s a gold mine.

There’s really two major bottlenecks to building more housing: the approval bottleneck, and the cost bottleneck. Even if something is legal to build, it won’t get built if costs are too high. The value of the new building, minus the total cost to construct it, has to be significantly greater than the value of the property with its existing building. Municipalities in Metro Vancouver extract a lot of development charges from new housing, part of the “all other costs” shown in turquoise. The city of Vancouver alone extracted $2.5 billion in supposedly voluntary “Community Amenity Charges” from 2011 to 2020.

There’s no such thing as a free lunch. Someone always pays. The argument is that these charges come from landowners, because they lower the price that projects are willing to pay for land. But once the “land lift” shown in green is gone, projects will have to wait until prices and rents rise higher. In other words, it’s homebuyers and renters who end up paying the higher costs.

In BC, the provincial government is also tackling the cost bottleneck, requiring amenity fees to be fixed rather than negotiated, and also requiring the fee schedule to be fixed. At the federal level, the federal government has waived the 5% federal value-added tax on new rental housing. A rough estimate is that this will result in 200,000 to 300,000 more rental apartments being built over 10 years.

More

Where America’s Fight for Housing Is an All-Out War. Francesca Mari, New York Times, February 2020. A review of Conor Dougherty’s Golden Gates: The Fight for Housing in America, which describes the origins of the YIMBY movement in San Francisco.

Dougherty expertly explains the confluence of microeconomic and historical forces that have created a housing shortage so severe that it’s rendered the most prosperous state in the country the poorest when adjusted for cost of living. To challenge readers to consider how change might be achieved, he features two very different YIMBYs. Sonja Trauss, the passionate but abrasive activist who rose to national prominence with her slash-and-burn tactics, raises the question, how far does one need to go to get results and how far is too far?, while the dryly diligent California state senator Scott Wiener shows how difficult it is to correct course legislatively.

Videos from YIMBYtown 2022 in Portland. Includes a presentation by Khelsilem and Danny Oleksiuk:

This is fantastic Russil. Keep up the great work!

You really put in the work, man; it's appreciated.