All the lights are flashing red, all the sirens are going off

A short presentation at a VANA social event

On Saturday, we had a Vancouver Area Neighbours Association social event at the Centre for Digital Media, including three presentations. Video.

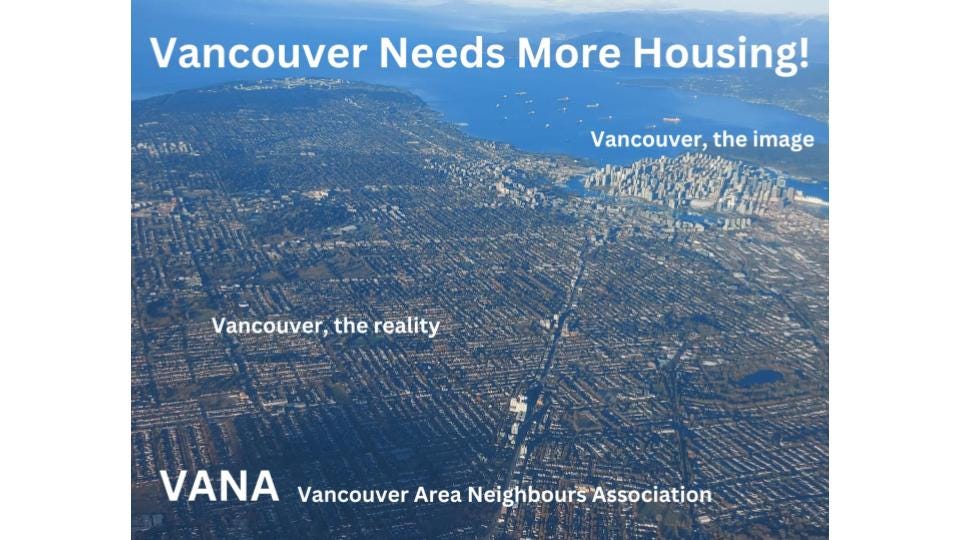

My presentation was about 20 minutes, with questions afterward. My aim was to talk about the gap between our current situation (a terrible housing shortage) and where we want to get to (more “gentle density” by right and more efficient use of our limited land), what’s blocking that from happening (the anti-growth institutions that have been in place since the 1970s), and what we can do to help.

“Anti-growth machine” is from Jake Anbinder’s recent paper.

Introduction

Hello, my name is Russil Wvong. Thank you for coming today! We’re the Vancouver Area Neighbours Association. We’re an informal but very active pro-housing community.

I should say up front that I’m not an expert, just an interested layperson and volunteer. My job has nothing to do with housing. I work as a software developer. But like most people in Vancouver, I find it maddening that housing is so scarce and expensive. We have two kids who are now young adults, and we’re wondering where they’re going to live.

I’m also involved in politics, especially with the federal Liberals, and I ran for Vancouver city council on Kennedy Stewart’s slate in the most recent municipal election. But housing cuts across the usual party lines. Every party, whether the NDP, the Liberals, or the Conservatives, has people who are pushing for more housing, and people who are skeptical.

I always like to give a summary up front. These are the main points to remember.

To go into more details, I’m going to talk about four things. First, why we need more housing. Second, what we need. Third, I’m going to talk about the anti-growth machine which slows down and blocks housing. Fourth, what we can do about it.

If you’re looking for a more authoritative account of what’s going on, I’d suggest taking a look at these references.

Where we are: a terrible housing shortage

So I’m going to start by describing why we need more housing. The housing shortage in Vancouver drives a huge number of other problems, making us worse off.

Housing is a ladder. It’s all connected. Higher up, housing is more expensive, but also more spacious, newer, and more secure. Lower down, housing is less expensive, but more crowded, older, and precarious.

What this means is that shortages higher on the ladder affect people further down the ladder. When you block new market-rate housing, the people who would have lived there don’t just vanish: they’ll find somewhere else to live, further down the ladder.

This makes housing more expensive at each lower rung of the ladder. You get trickle-down evictions, displacement, and tremendous pressure on people closer to the bottom. They’re forced to move away, to crowd into substandard housing, or worst of all, end up homeless.

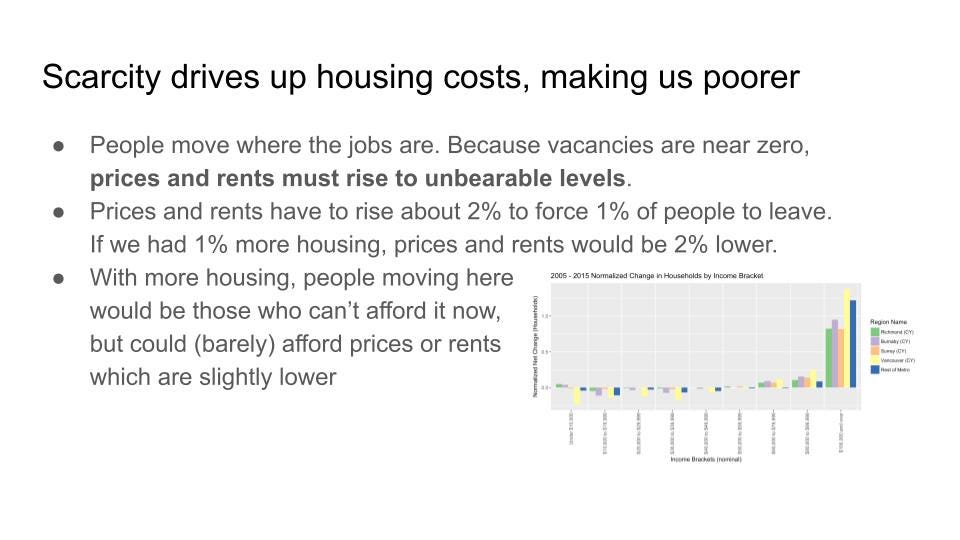

Because Vancouver has lots of jobs and not enough housing, prices and rents have to rise to unbearable levels, forcing people to give up and leave. That’s the reason that prices and rents are completely decoupled from local incomes. To be a little more precise, the estimate is that prices and rents have to rise about 2% in order to force 1% of people to leave.

Equivalently, if we had 1% more housing than we actually do, housing costs would be about 2% lower. The people who would be able to live here are people who can’t afford it right now, but who could just barely afford it if housing costs were a bit lower.

You can see that in 2015, you couldn’t afford to move here unless you had a household income of $100,000 or more, and the barrier has only gotten higher since then. It acts like a one-way filter that keeps younger people out.

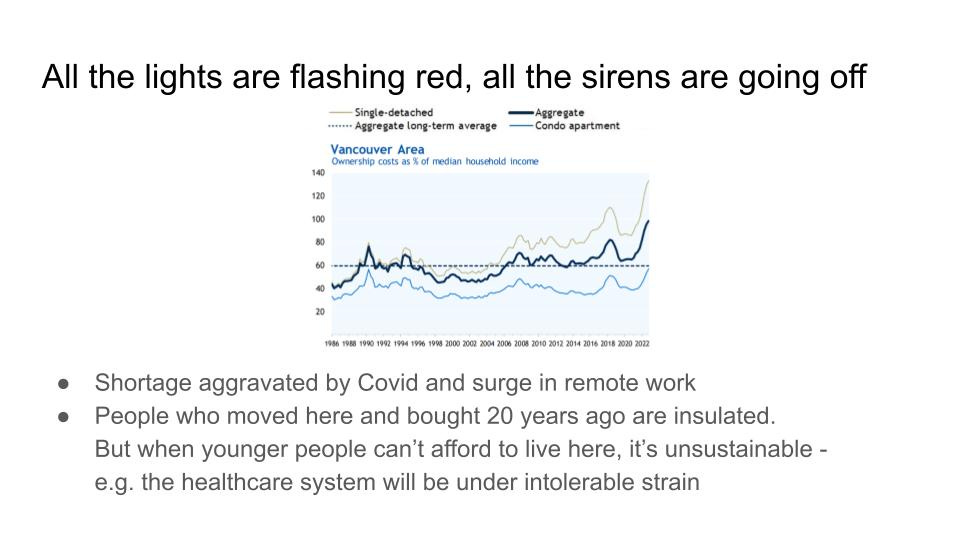

You sometimes hear people say that housing in Vancouver has always been expensive. But this graph from RBC, going back to 1986, shows that it really is getting much worse. When Covid hit, there was a sudden massive surge in people working from home and needing more space. So now we have an even worse shortage of residential space, and a surplus of office space. Plus we’ve had post-Covid population growth on top of that, although the federal government is now cutting that way back.

It’s obviously a terrible situation for younger people and renters, but whenever I’m talking to older homeowners, I emphasize that it’s bad for them as well. Even if they’re insulated from the housing market, we all depend on the healthcare system. When younger people can’t afford to live here, hospitals will find it harder and harder to hire nurses and even doctors. The healthcare system is going to come under increasing strain.

Because housing costs are high, real incomes are lower. After paying your rent, or paying for a mortgage, you don’t have much left over.

And then lower real incomes result in labour shortages. We have this situation where employers can’t find workers, and at the same time, workers can’t find jobs that pay enough to live on. There’s stories all the time about shortages of nurses, teachers, and police officers in Metro Vancouver.

What we need: more density where land prices are high

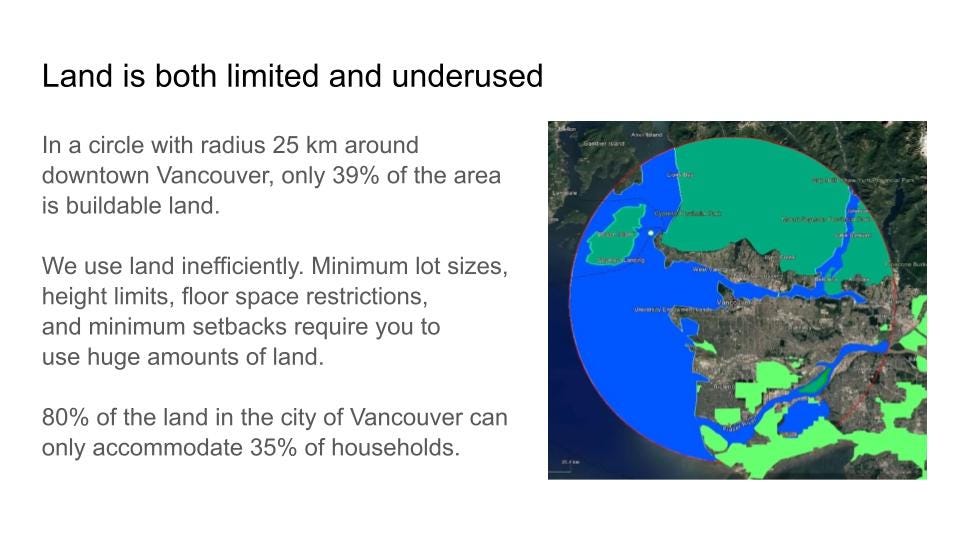

Next I’d like to talk about what we need. Basically, we need more density. Vancouver has a lot of underused land, as we saw from the aerial shot.

Land in Metro Vancouver is very limited, because of the ocean and mountains. Because land is so scarce, it’s particularly important to use it efficiently. But we have a lot of regulations that require you to use huge amounts of land. There’s mandatory setbacks requiring you to have a large front yard, for example, which nobody ever uses.

The result is that houses are very expensive because they’re required to sit on a large amount of underused expensive land.

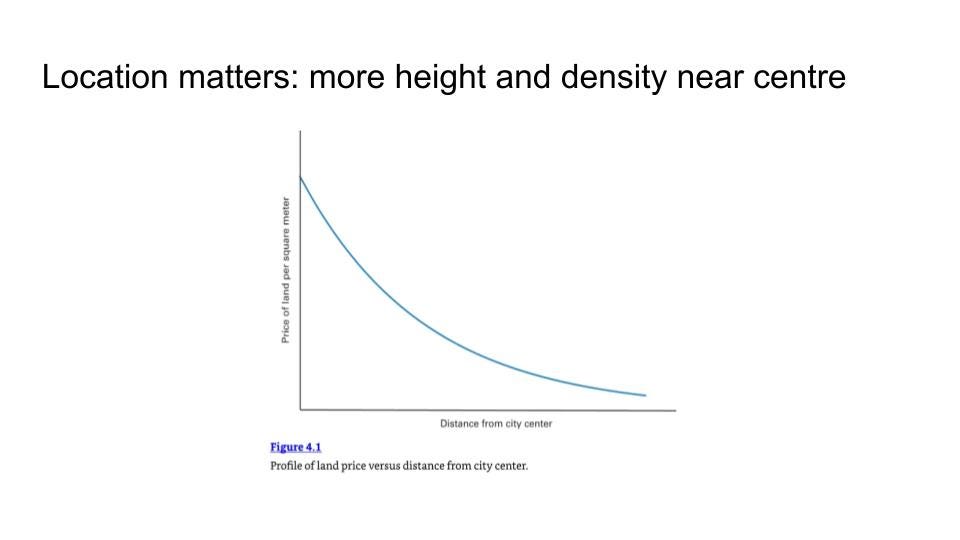

It also matters where you build housing. You’ll have more people wanting to live in a geographically central location, with easy access to lots of jobs. That means land prices will be higher there. For Metro Vancouver, that means the city of Vancouver.

The more expensive the land is, the more housing you should allow on it. A rule of thumb is that the cost of land for a new building should be about 20-25% of the total cost. In other words, you should be able to build something that’s worth about 4-5X as much as the land. If you’ve got a lot in East Vancouver worth $1.5M, and floor space is worth about $1000 per square foot, you should be able to build about 6000 to 8000 square feet of floor space on it. That’s about three or four storeys.

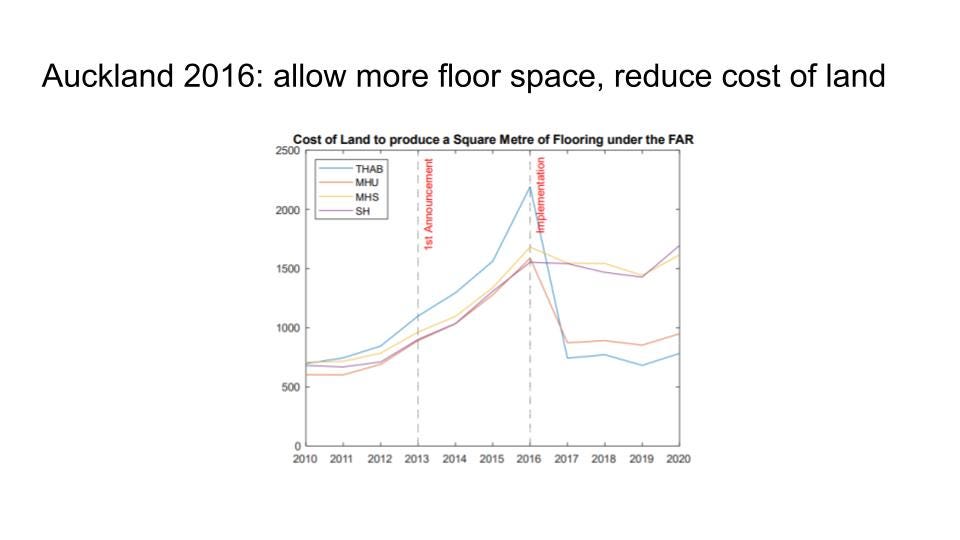

By allowing more floor space on a given parcel of land, you can reduce the cost of land per square foot of floor space. This graph shows what this looked like after Auckland allowed more housing in 2016, like townhouses and small apartment buildings.

Where land prices are particularly high, like within walking distance of a city centre or a SkyTrain station, it makes sense to allow high-rises. But high-rises take a long time to plan and build, so if we want to add a lot more housing quickly, it makes sense to do something like Auckland did.

If we build a lot more low-rise and mid-rise apartment buildings in Vancouver, how livable will they be?

Someone who grew up in the Kootenays lived in Palermo, Italy several years ago, staying with a family who lived in a middle-class apartment. She described it as being very spacious and comfortable. It had the same total floor area as the split-level where she grew up, but on a single floor. There were four apartments on each floor, facing onto a central courtyard, so every room in the apartment had a window. A courtyard like this is also a good shared space for kids to play.

There’s a specific issue that would help. European apartment buildings are built around a single central staircase, with a small number of apartments per floor. Each apartment typically has windows on at least two sides, so you can get cross-ventilation. If the building is on a busy street, you can put the bedrooms away from the street. In Vancouver you usually have a hotel-style layout with a long hallway between two exit stairwells. The province is looking at making it legal to build more European-style apartment buildings with a single staircase. Seattle’s allowed six-storey apartment buildings with a single staircase since 1977.

The anti-growth machine

Next I’d like to talk about the details of the anti-growth machine, the set of institutions we have that slows down or blocks housing.

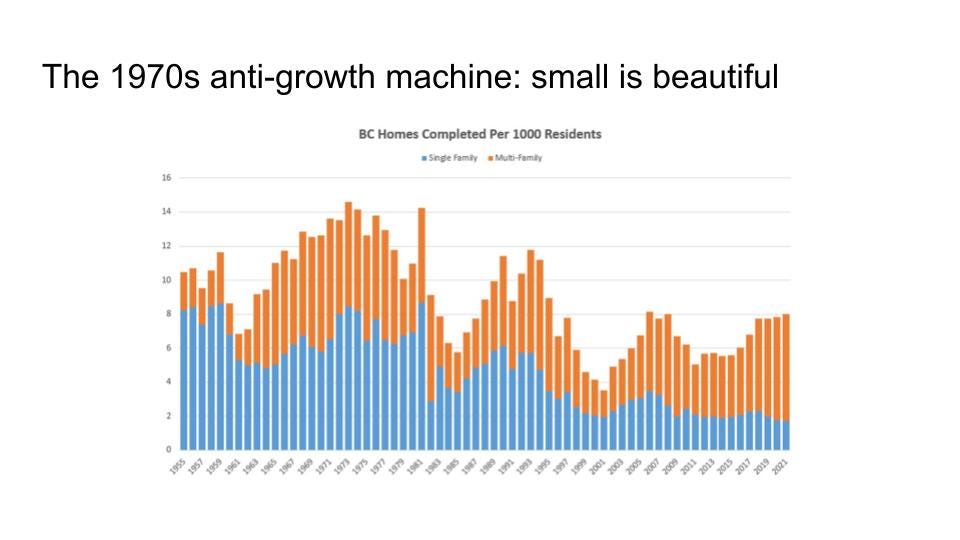

Before 1970, there wasn’t much difference in housing costs between places like California and the rest of the US, or between Vancouver and cities like Winnipeg. Cities generally had a pro-growth attitude, encouraging more businesses, more jobs, and more housing. In the early 1970s, there was a significant political shift away from growth towards more of a “small is beautiful” view, in both Vancouver and in other cities like San Francisco and New York. Cities made it much more difficult to build new housing.

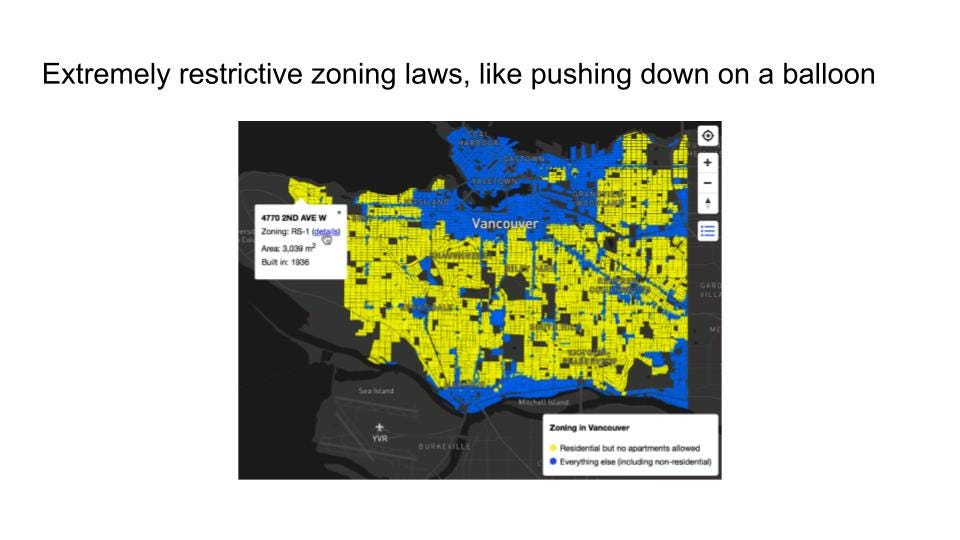

This map by Reilly Wood illustrates that in most of the city of Vancouver, it’s illegal to build an apartment building. Because the city of Vancouver is geographically central, with easy access to lots of jobs, many people would like to live here. So having such restrictive zoning is like pushing down on a balloon. People don’t disappear, they get pushed out to Burnaby and Surrey. Even Langley is now building high-rises.

For example, there’s an eight-unit, two-storey rental apartment building at 1000 Cypress Street in Kits Point, built in 1972.

It’s reached the end of its useful life. Instead of being replaced with a new apartment building of the same size, it’s being replaced with three single-detached houses. Under the city’s zoning laws, that’s all that’s legal to build.

You can see that the city’s zoning laws are suppressing a truly huge amount of demand by walking five minutes south on Chestnut Street. You come to the Senakw project, across the Burrard Bridge from downtown. On this relatively small parcel of land, the plan is to build 60-storey high-rises, with 6000 rental apartments, 20% below-market.

The only reason this can happen is that the project is on Squamish reserve land, so it’s not subject to the city’s zoning restrictions.

One of the most obvious ways to address Vancouver’s housing shortage is that we should let people build more desperately needed housing.

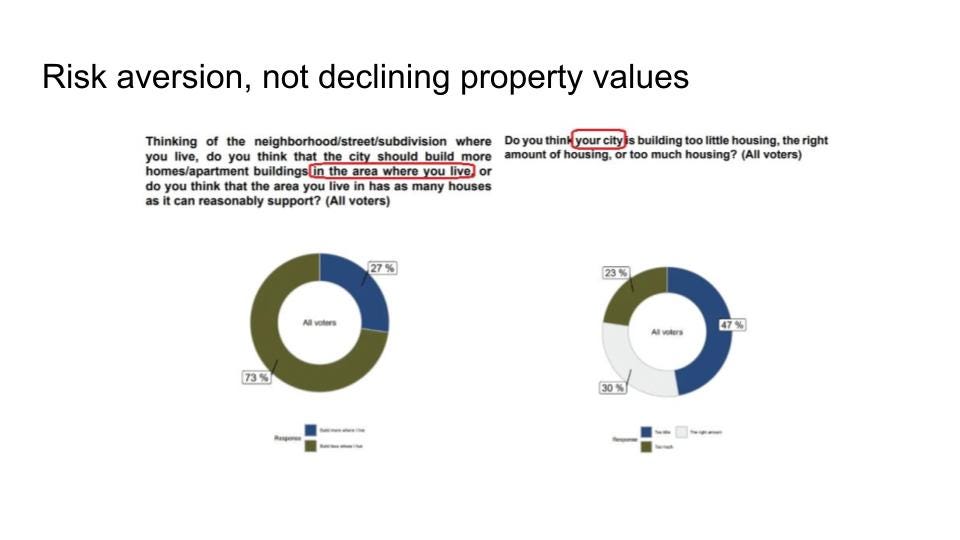

When I talk to politicians I sometimes hear, oh, we can’t do anything, because most voters are homeowners and they’re going to oppose anything that would result in lower property values.

I actually think homeowner opposition to new housing is primarily driven by fear of change to their immediate neighbourhood, rather than fear of falling property prices. Opposition tends to be hyperlocal.

This is a poll from Toronto. You can see that when you ask, should the city allow more housing in your neighbourhood, most people say no. But when you ask the same people, should the city allow more housing, which is what would put downward pressure on prices, most people say yes.

I also like to remind politicians that in the most recent municipal election, Colleen Hardwick ran for mayor, appealing to people who fear and oppose new housing. She only got 10% of the vote.

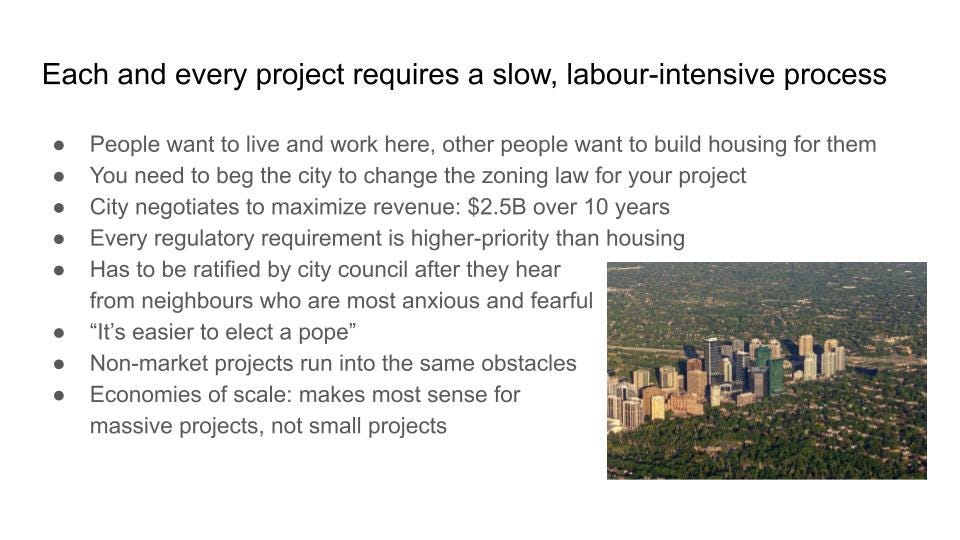

In terms of the mechanics of the anti-growth machine, there’s two major parts. One is the very slow and labour-intensive approval process.

Because prices and rents are so high, there’s very strong incentives for people to build more housing. The problem is that it’s very difficult to get approval. Basically you need to beg the city to change the law. There’s a dense thicket of regulatory requirements which has grown up over time, enforced by city staff. They’re all higher-priority than housing, because if they’re not met, the answer will be no.

The most visible and spectacular part of the process is the public hearing. These are livestreamed on YouTube and you can watch them afterward. I’ve got several examples linked to morehousing.ca. This is where city council sits through a presentation explaining why the law should change for this specific project, then listens to the neighbours who are most anxious and fearful about the project, and then votes on whether to approve the change to the law.

As Ginger Gosnell-Myers says, “It’s easier to elect a pope.”

Non-market projects run into exactly the same obstacles. Even when BC Housing is providing hundreds of millions of dollars in funding for non-market apartments, they still have to go through the slow and laborious process of convincing city staff and city council to say yes. There’s a number of cases where non-profits have had to give up.

Because this process is so onerous, it makes a lot more sense for a massive project than for a small project. You get economies of scale: you can spread the cost over a large number of apartments. That’s why we tend to have either single-detached houses or high-rises.

So why does the city have such a slow and stupid process? Why does the city only allow the most expensive form of housing, a single-detached house sitting on a lot of land, to skip this process?

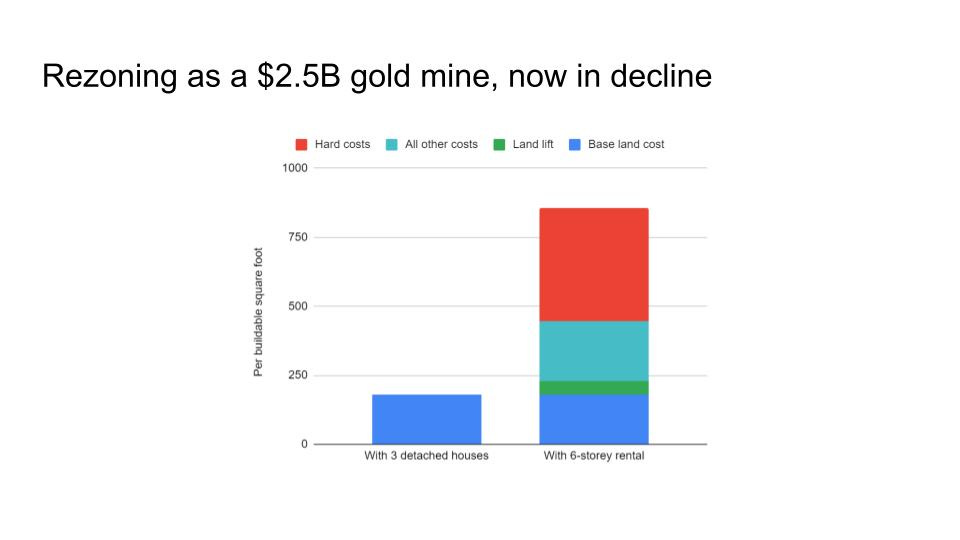

The answer is that people really dislike property taxes. Unlike income tax, you get your property tax bill once a year, and you need to pay it all at once. By making it illegal to build apartment buildings, the city can negotiate to take most of the potential profit whenever it changes the law so that somebody can build one. Over the 10 years from 2011 to 2020, the city of Vancouver collected $2.5 billion in supposedly voluntary “Community Amenity Contributions.” That allows the city to keep property taxes low.

If we want to build more desperately needed housing, reducing costs is really important. Even when something is legal, if costs are too high it won’t get built. A project doesn’t make sense unless the value of the new building, minus all the costs of building it, is high enough. That’s basically how much the project can pay for land. It’s volatile, it goes up and down a lot. It has to be significantly higher than the current value of the property with its existing building, or the landowner won’t have an incentive to sell, and nothing will happen.

This graph shows an analysis by Coriolis, from May 2022, of a six-storey rental project in Vancouver. With rents at that time, the value of the new building would be about $860 per square foot, the total height on the right. The “hard costs” for labour and materials are about half of that, shown in red. All other costs, including Community Amenity Charges and GST, are shown in turquoise. Subtracting those costs, you get $230 per buildable square foot that the project can pay for land. The value of the land with its existing buildings is $180 per square foot, shown in blue. So that leaves $50 per buildable square foot in “land lift” that motivates the landowners to sell, shown in green.

As costs rise, the green part shrinks. When it’s too small, the landowners aren’t interested in selling, and nothing happens until prices and rents rise enough for the project to make sense. In other words, cost increases are first absorbed by land lift, but once that’s gone, they end up being paid by homebuyers and renters. It doesn’t just affect prices for new buildings, it also affects prices for existing buildings, since they compete with each other.

One thing I should point out is that because house prices are rising, and construction costs are also rising, redevelopment land values have been dropping. In other words, this green part is being squeezed more and more. There’s two ways to respond. One is to reduce the turquoise part of the graph, “all other costs.” The other is to allow more Vitamin D, or density, as Michael Mortensen puts it, so that you can spread the costs over more buildable square feet.

How do we fix this?

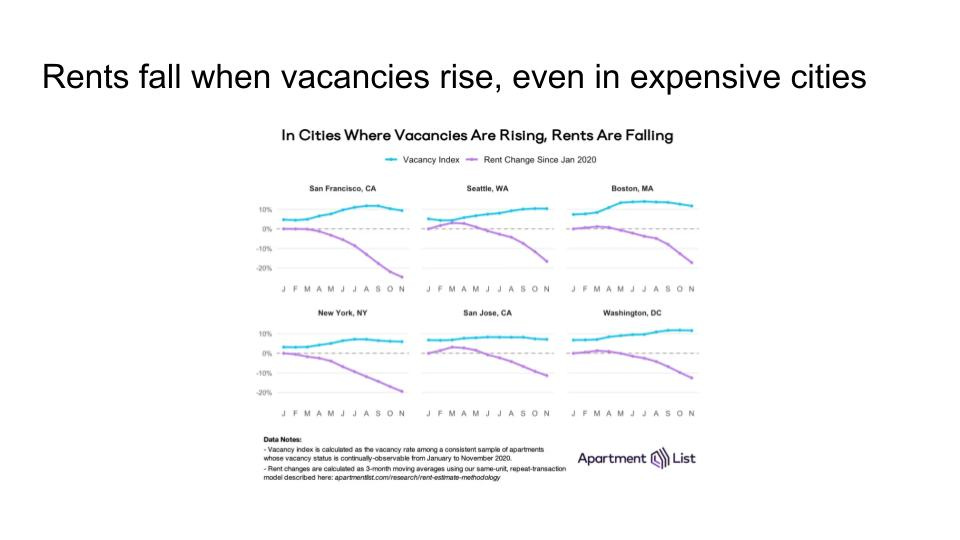

So how do we fix this? The most important thing is to build more housing. This slide shows some recent evidence from 2020 that when vacancies go up, rent goes down, even in expensive cities. Again, for Metro Vancouver, the estimate is that if we had 1% more housing, housing costs would be 2% lower.

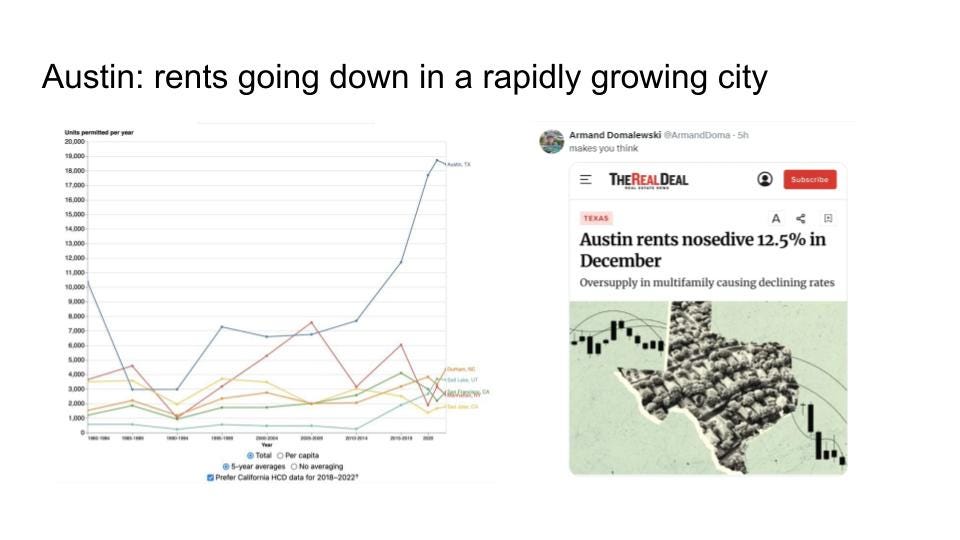

Prices and costs are always shifting around, so when there’s an opportunity to build a lot more housing, we should always be taking it. Austin was growing rapidly during Covid and rents were going up, so a lot of people launched projects to build more apartments. Now they’ve got an oversupply and rents are dropping, which is great.

I mentioned that Auckland reformed their land use in 2016 to allow more townhouses and small apartment buildings. So we have six or seven years of data. They built a lot more housing, putting downward pressure on prices and rents.

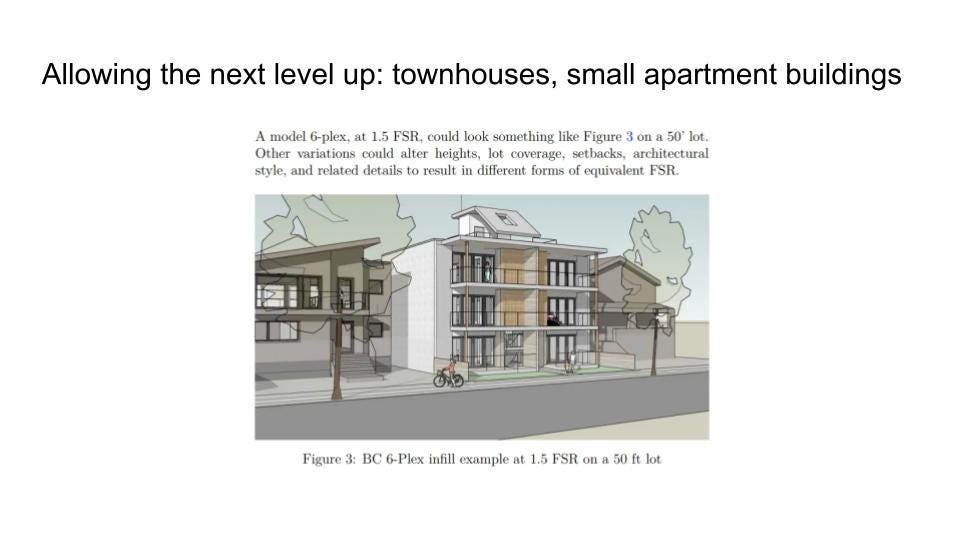

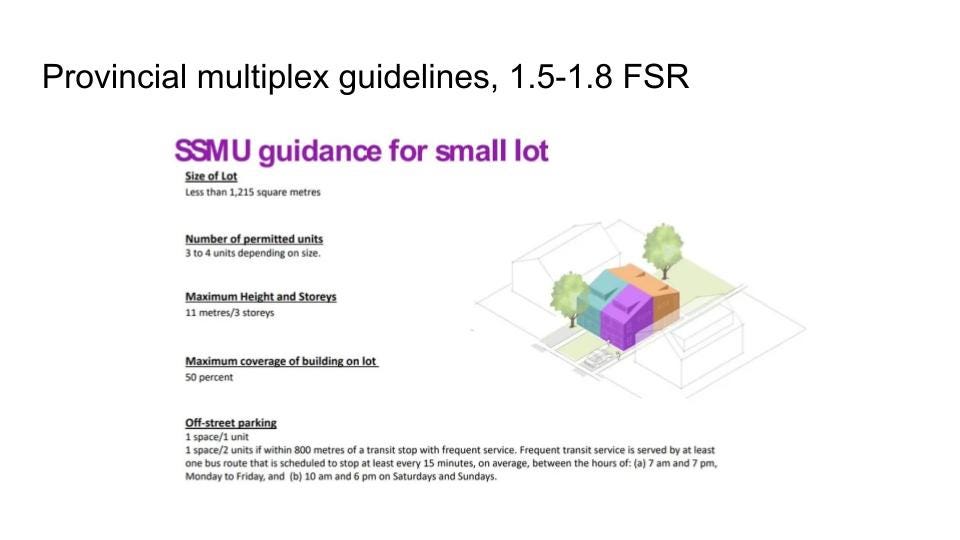

BC is doing something very similar, requiring municipalities to update their zoning laws to allow four- and six-plexes by right, and to allow high-rises within walking distance of SkyTrain stations and major bus exchanges. A team of economists prepared a detailed economic model, and they estimate that over 10 years, this will result in 200,000 to 300,000 additional homes. That’ll get us about halfway to filling the supply gap.

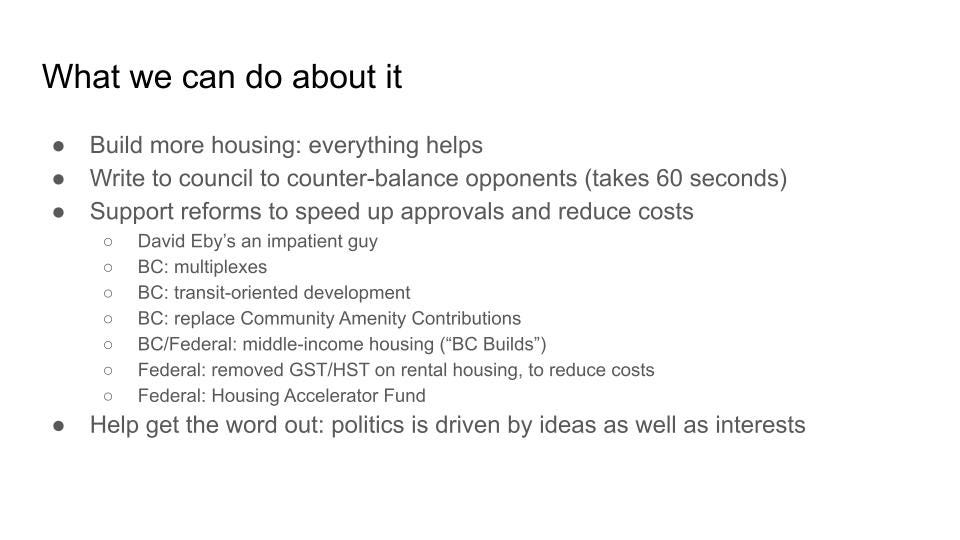

In this slide I’ve tried to summarize the main things that we can do. Obviously the overall goal is to build more housing. New housing frees up older housing. Every time a new building opens up with 100 or 200 apartments, whether it’s market or non-market, that’s 100 or 200 fewer people who are competing with everyone else for existing housing.

Under the current site-by-site approval process, it’s important to counter-balance opponents of housing, to make sure that city council isn’t just hearing from opponents. Whenever we hear that there’s some project that is running into a lot of opposition, we mobilize people on Reddit to write in support. Opposition is typically hyperlocal, but if you ask a wider range of people across the city, you’ll get overwhelming support.

Further upstream, we can support reforms to speed up approvals and reduce costs. One thing that really helps is that David Eby is an impatient guy. Besides requiring municipalities to allow multiplexes and transit-oriented development, they’re also putting $2 billion into middle-income housing on public land, matched by another $2 billion from the federal government.

A specific way we can support reforms is to volunteer in elections where housing is going to be an issue, like the upcoming provincial election in October.

We can also help by getting the word out, talking to people in person and on social media. I like to emphasize that when younger people are being crushed and driven out of the city by the scarcity and cost of housing, the healthcare system is going to be in trouble. Politics is driven by both ideas and interests. People want to know how policies will affect them, but they also know that we live in a society, and they want to support policies that are good for society as a whole.

If you’d like to get involved with VANA, please come talk to me afterwards. Or if you’re watching this online, you can find me at morehousing.ca.

Thank you for your time!