Trump 2.0: macroeconomic populism

Hope for the best, plan for the worst

If Trump wins tomorrow’s US presidential election, one likely scenario is macroeconomic populism: more tax cuts, more spending, and high inflation. Dornbusch and Edwards, 1991, describing macroeconomic populism in Latin America:

Again and again, and in country after country, policymakers have embraced economic programs that rely heavily on the use of expansive fiscal and credit policies and overvalued currency to accelerate growth and redistribute income. In implementing these policies, there has usually been no concern for the existence of fiscal and foreign exchange constraints.

After a short period of economic growth and recovery, bottlenecks develop, provoking unsustainable macroeconomic pressures that, at the end, result in the plummeting of real wages and severe balance of payment difficulties. The final outcome of these experiments has generally been galloping inflation, crisis, and the collapse of the economic system. In the aftermath of these experiments there is no other alternative left but to implement, typically with the help of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a drastically restrictive and costly stabilization program.

The self-destructive feature of populism is particularly apparent from the stark decline in per capita income and real wages in the final days of these experiences.

Because Canada’s economy is closely integrated with the US economy, it’s possible that we could see similar impacts: high demand to the point of overheating, followed by collapse.

In the overheating stage, we’d expect to see tighter monetary policy (higher interest rates) and tighter fiscal policy (smaller deficits) in Canada.

In the post-collapse stage, we’d see higher unemployment, looser monetary policy, and looser fiscal policy. Higher unemployment and uncertainty would reduce demand for housing, but perhaps countercyclical policy could keep homebuilding going.

A further complication is that Trump is also planning an across-the-board 10% tariff on all US imports. Canada will be doing everything we can to get an exemption (similar to the cross-party efforts to preserve NAFTA during Trump 1.0). If we can’t, then the reduction in demand for Canadian exports will tend to cool the Canadian economy, resulting in higher unemployment.

Finally, Trump is promising to deport millions of illegal immigrants from the US. It’s possible that this would result in lots of people moving to Canada instead of the US.

Why is it so close?

Nate Silver’s assessment of the US presidential race is that it’s basically 50/50.

I’ve never seen an election in which the forecast spent more time in the vicinity of 50/50, and I probably never will.

There’s another, more advanced property of probabilistic forecasts that sports gamblers (or otherwise highly quantitatively-minded sports fans) intuitively understand. It’s late in this election and the Electoral College is close. When a game is late and close, then tiny things — a single point or goal or run scored — can make a huge difference. Here, for instance, is an estimated win probability chart for an NBA game for a team that has possession of the ball with two minutes left to go in the fourth quarter; say it’s the Knicks down 106-105 to the Celtics. If Jalen Brunson is fouled and makes both free throws, the Knicks’ win probability shoots up from 45 percent to 69 percent; that’s absolutely huge.

Joseph Heath, discussing Rob Ford (the crack-smoking mayor of Toronto) back in 2014, explains the appeal of demagogues. Usually we can rely on political parties to screen them out.

Many people in Toronto have been shaking their heads this past year and saying to themselves “What have we done to deserve this?” And looking at Ford’s stubbornly high popular approval ratings, many have also been wondering – as my wife put it – “What the fuck is wrong with people in this city?”

So by way of comfort, I want to point out that there is nothing special about Ford, or the Toronto electorate. Ford is nothing but the most recent instance of an archetype that has been with us literally since antiquity. Readers of Plato and Aristotle are familiar with the character – Ford is a textbook illustration of a demagogue. He is an almost cookie-cutter version of a type that has appeared and reappeared in democratic political systems since as long as they have existed.

Just to establish that there is nothing special or unprecedented about Ford, consider this 1838 profile of “the demagogue,” taken from James Fenimore Cooper’s essay on the subject. Cooper described demagogues as possessing four qualities:

(1) They fashion themselves as a man or woman of the common people, as opposed to the elites;

(2) their politics depends on a powerful, visceral connection with the people that dramatically transcends ordinary political popularity;

(3) they manipulate this connection, and the raging popularity it affords, for their own benefit and ambition; and

(4) they threaten or outright break established rules of conduct, institutions and even the law.

The people who wind up getting put forward to the electorate, by political parties, do not have all that much in common with ordinary citizens. They are more like contestants on Jeopardy – the product of a huge pre-screening process, which goes on behind the scenes. We tend to take it for granted, though. As a result, much of the electorate has become accustomed to exercising the vote irresponsibly. They look at the ballot and assume that all the major candidates are more-or-less capable of doing the job, and that the differences between them are minor ones of political ideology. The thought that one of the major candidates might be a total fuck-up just doesn’t cross most people’s minds.

A first-hand comment from John Culver, former national intelligence officer for East Asia:

I’ve been in the room with Trump many times. Vote for Harris.

Trump 1.0 vs. Trump 2.0

One reason why a second Trump government is likely to be very different from the first is that in 2016, Trump wasn’t prepared to win.

Michael Lewis, The Fifth Risk:

Chris Christie was sitting on a sofa beside Donald Trump when Pennsylvania was finally called. It was one thirty-five in the morning, but that wasn’t the only reason the feeling in the room was odd. Mike Pence went to kiss his wife, Karen, and she turned away from him. “You got what you wanted, Mike,” she said, “now leave me alone.” She wouldn’t so much as say hello to Trump.

Trump himself just stared at the tube without saying anything, like a man with a pair of twos whose bluff has been called. His campaign hadn’t even bothered to prepare an acceptance speech. It wasn’t hard to see why Trump hadn’t seen the point in preparing to take over the federal government: Why study for a test you’ll never need to take? Why take the risk of discovering you might be at your very best a C student? This was the real part of becoming president of the United States. And, Christie thought, it scared the crap out of the president-elect.

Large deficits aren’t driving US growth

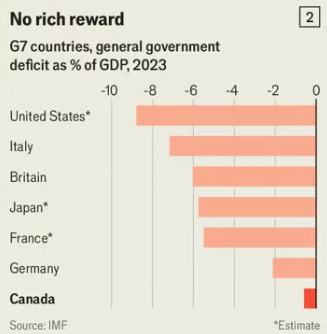

One obvious difference between the US and Canadian economies is that US fiscal policy is already much looser (running larger deficits). Economist: “Unlike Uncle Sam, Canada’s government has not tried to soften the blow by loosening the purse strings. Canada ran a deficit of just 1.1% of GDP in 2023, compared with 6.3% in America.” Across all levels of government:

And the US economy is also growing significantly faster than other rich countries, including Canada:

But as Matthew Yglesias points out, large deficits are not what’s driving US growth. By requiring tighter monetary policy (higher interest rates), they’re slowing investment and growth, not accelerating it.

A commenter asked:

How much of recent US economic outperformance is just debt-driven? I think we've all heard that the US is growing faster than any other developed country for a while now, post-Covid but also really post-global financial crisis. However, we've also taken on the most debt. Are we just experiencing debt-fueled growth? Which obviously has a hard limit somewhere.

Matthew Yglesias:

Debt can generate prosperity when the economy is operating well below potential. That was the situation for most of Obama’s presidency — more debt meant more growth, but the politics pointed to deficit reduction. Then Trump became president and raised military spending, but also raised non-military spending and also cut taxes, which boosted growth.

Today, though, the economy is at full employment.

This means the scale of the 2024 budget deficit is not providing useful stimulus to the economy. Which also means that the downside of that debt isn’t occurring at some hypothetical time in the future, it’s happening right now.

Specifically, in 2021 and especially 2022 an overstimulated economy generated a burst of inflation, then in 2023 and 2024, we got that inflation under control with higher interest rates from the Federal Reserve. But those higher rates had a direct, immediate cost to the American private sector in the form of higher costs for mortgages, auto loans, small business loans, and other credit products.

Which is just to say that today’s economy is humming, not because of debt accumulation, but despite it. What we need now more than anything is a prudent program of deficit reduction to bring private sector interest rates down.

Of course that’s not what we’re going to get:

What voters want from Trump is a return to Trump-era conditions, with low inflation and interest rates.

But Trump 1.0 started from a position where higher deficits were useful, and he acted to make deficits much larger. Today, Trump is starting from a position where the deficit is too high, and he’s promising to make the deficit dramatically larger. This is a really bad idea — and it doesn’t even include the idea he keeps floating to replace the entire income tax with taxes on imports.

If you did this, it would not “juice” the economy, it would put massive upward pressure on inflation and interest rates.

More

Republicans’ Closing Argument: We Will Wreck the Economy. Matthew Yglesias, Bloomberg. “In the closing days of the presidential campaign, Donald Trump’s business allies suddenly have a new message: The US needs sharp, immediate and ill-defined spending cuts.”

The only thing you can be sure of, is that the most-left party around will be blamed for economic hardship:

http://brander.ca/stackback#yycrecession

...relates how the Calgary hard times that started in 2014 were blamed on the Notley government that took office 11 months later, and the Trudeau government that took office sixteen months later, than the oil-price crash of summer 2014. I'm not talking about social media posters or bloggers; Chris Nelson of the Calgary Herald is called out.

The American economy is going on so many jets right now that it will take Trump most of four years to crash it, so that the incoming Democrats can take the blame.