Report on City-wide Utilities Financing Growth Strategy and Cambie Corridor Utilities Servicing Plan, July 2018.

The need for sewers

When you have more housing and more people in a neighbourhood, you need to build up public services and infrastructure as well. Schools, child care, community centres, parks, public transport - and sewers.

The sewer system is the network of pipes which carry away wastewater (“sanitary sewers”) and stormwater (“drainage”). It’s like a tree, with individual households as the leaves of the tree, the sewer mains on each street as branches leading to larger trunk lines (shown above), and a final trunk leading to the Iona Island wastewater treatment plant.

Upgrading Vancouver’s sewer system

Vancouver’s sewer system was mostly built in the 1950s and 1960s, as a combined system. The same pipes carry both wastewater and rainwater, which means that when you get a lot of rain, you can get sewer backups and overflows. The estimated replacement cost for the city of Vancouver’s wastewater and stormwater systems is about $8 billion, and the expected lifetime of a sewer pipe is about 100 years.

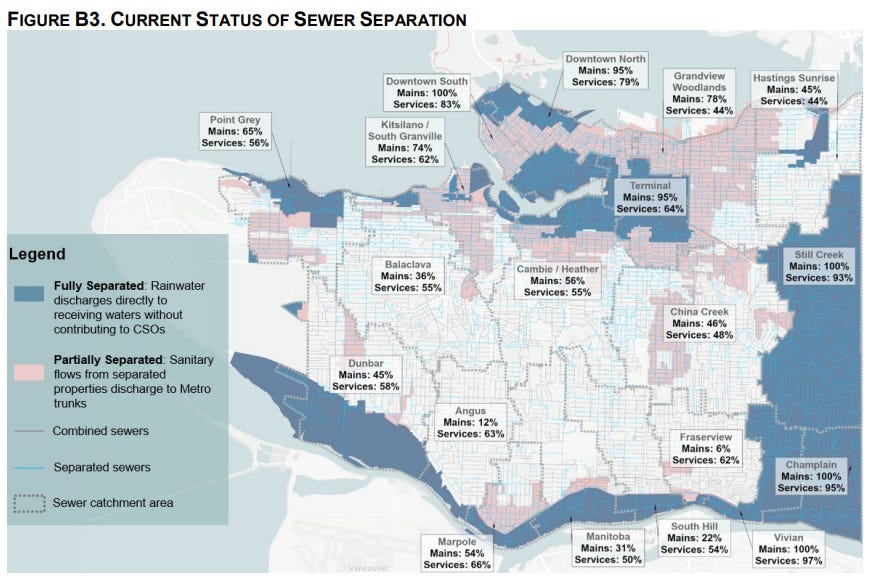

The city has a long-term program to replace the combined sewers with separate pipes for wastewater and stormwater - in effect, adding a second network that takes rainwater directly to the ocean or the Fraser River without being mixed with wastewater. The city is also reducing stormwater runoff, which can still be polluted, with surfaces which absorb and release water more slowly, like a giant sponge (“green infrastructure”).

The basic idea is to replace about 1% of the pipes each year. (The expected lifetime of a sewer pipe is about 100 years.) The target date to complete the sewer separation is 2050.

A couple cases where sewer capacity appears to be a major constraint on building more housing:

There’s a lot of land within walking distance of a SkyTrain station which is restricted to single-detached houses and duplexes. In an August 2021 article about sewers, Frances Bula noted that the city hadn’t yet upgraded the sewers near the Nanaimo and 29th Avenue SkyTrain stations.

The city of Vancouver’s multiplex proposal sets a restrictive floor space limit (1.0 FSR). One of the key reasons given is that there’s neighbourhoods where the sewers haven’t been upgraded yet. In particular, more impermeable surface area results in more stormwater runoff.

Planning for utilities city-wide

A Redditor mentioned that the Cambie Corridor plans from 2018 include a detailed discussion of the sewer upgrade plan. Naturally I looked them up and read them.

Report on City-wide Utilities Financing Growth Strategy and Cambie Corridor Utilities Servicing Plan, reviewed at the July 11, 2018 meeting of the Standing Committee on City Finance and Services.

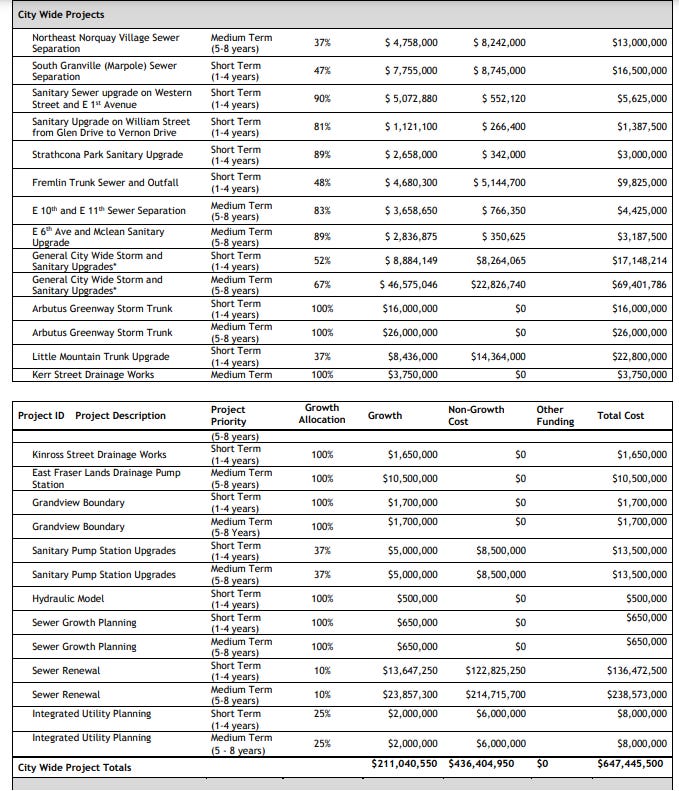

The basic idea is to have an overall city-wide plan, with $1B in utilities capital spending over eight years, and to allocate part of the costs to new development, in the form of a new Utilities Development Cost Levy (p. 3).

Having a fixed DCL is preferable to the current process of negotiating payment during the rezoning (pp. 7-8), which results in a number of problems, including

Lack of clarity on the extent of required upgrades at project outset - Creates challenges in negotiating land acquisitions.

Perceived inequity among developments - Development applications near recently upgraded mains ‘win’ and only need to connect to the main, while others adjacent to a system near capacity could be responsible for significant off-site upgrades.

Results in patchwork upgrading of the utility networks – Lost opportunity to plan or design at the neighbourhood or district scale level; addresses only local conditions.

A detailed list of capital projects for 2019-2026 was prepared by Urban Systems, in Appendix E. The selection criteria are described on pp. 11-12: basically, figure out where the utility networks (wastewater, stormwater, water supply) need to be upgraded based on growth projections, and group them into projects. When developing an area plan, plan for the utility infrastructure at the same time.

Upfront development charges vs. usage charges

An interesting comment from page 23:

For comparative purposes, if the proposed utilities work ($550 million) were to be funded from property tax and utility fees instead of the proposed Utilities DCLs, it would require a 4.2% tax increase, 40% sewer fee increase and 5.4% water fee increase. This is not recommended as it does not align with the principle of ‘growth pays for growth.’

I’ll just observe that Benjamin Dachis recommends the exact opposite. How High Municipal Housing Charges and Taxes Decrease Housing Supply, November 2020:

First, change upfront development charges on developers into per-usage fees to be paid by the ultimate homebuyer. Those buyers already end up paying higher costs due to these upfront charges to developers. Lower upfront charges will lower housing costs. This is most workable for water and wastewater charges. These are usually the largest single upfront charge that developers face. Charging the full cost of water-related capital and operations in a per-usage fee on services will also lead to less water wastage.

With the new Utilities DCL, East Side projects are less economically viable (pp. 12-14).

I don’t understand the rationale for higher charges for higher-density housing (weighting factors, p. 57). I would have expected the amount of wastewater to be proportional to floor area.

Finally, despite the comments on pp. 7-8 about the problems when negotiating payment for utility upgrades during rezoning, it may still be required:

If neighbourhood-serving infrastructure to the development site is not included in the Utilities DCL Capital Program, then the developer is responsible.

February 2023 update

Update on development of sewage and rainwater management plan (“Healthy Waters Plan”), reviewed at the February 1, 2023 meeting of the city finance and services committee meeting.

If I understand correctly, it’s saying that the city’s been falling behind on the 1% per year / 2050 target (p. 14). It recommends increasing spending to achieve a rate of 1% per year, aiming for 2060 (p. 22). (I think Kenneth Chan at the Daily Hive may have misinterpreted the report - it’s not calling for an increase to $100M/year to achieve a rate of 1.6% and meet the 2050 target.)

If I understand correctly, the map of sewer renewal areas for 2027-2032 includes Nanaimo station and the area within walking distance of 29th Avenue station to the west. (The area east of 29th Avenue station is within the Still Creek sewer catchment, which has already been upgraded.)

Open questions

What I’d still like to know:

Housing in Vancouver being so scarce and expensive has a tremendous cost, making us poorer by reducing our real incomes. If more funding is available (through property taxes or through transfers from the provincial or federal governments), can the sewer upgrade program be accelerated further? Are there bottlenecks other than funding?

If we can fix the housing scarcity problem, it seems likely that the city of Vancouver’s population growth over the next 50 years will turn out to be significantly greater than currently projected. How much growth can the recently upgraded sewers handle?

Are there sewer upgrades required along Broadway which could be done now, while the street has been opened up for the construction of the Broadway Subway?

More

Video by Uytae Lee on sewer separation and green infrastructure: How to Stop Dumping Sewage into the Water, April 2023.

Interactive map of Vancouver’s sewer mains, from the city’s Open Data Portal.

Integrated Liquid Waste and Resource Management Plan, 2010. Metro Vancouver’s wastewater plan, from Metro Vancouver’s liquid waste website.

B.C. sets aside $250 million to upgrade the Iona wastewater treatment plant, March 2023. That certainly helps, but there’s still a lot of funding required - the total estimated cost is $10 billion.

A couple articles from trade publications, providing a ground-level view. An article by Christopher Lamont in Trenchless Technology, April 2023, describing a project in Edmonton: Groat Road Storm Trunk Sewer Rehabilitation Phase 2. An article by Jennifer Winter in Municipal Sewer & Water, August 2014, describing different materials used for water and wastewater pipes: A Pipe for Every Project.

Sewer backups in Vancouver (where wastewater flows out of your toilet) typically occur because the pipe connecting the property to the main sewer is blocked by tree roots. There’s about 1000 incidents reported to the city each year. Sewer-backup prevention devices have been required in new construction since 2018, but they can also be retrofitted.

You got to this topic fast! Great writeup.

I think they are upgrading the sewers along broadway, at least I've seen construction notices for "sewer upgrades". This might just have meant that they were moving pipes out of the way however.