Optimism vs. pessimism

"Housing always goes up"

I wrote up a post on Vancouver and Winnipeg home prices being comparable as late as 1988, and it was posted to Reddit. It got a lot of comments. There was a strong strain of pessimism, e.g.

It fucking sucks that depending on how old you are/your generation, not getting into the housing market when it was affordable is not due to poor financial planning (as many people will accuse) but due to the fact that one was a child when housing was affordable.

Should we be optimistic or pessimistic about housing in Vancouver?

Negativity bias makes it easy to be pessimistic. Home prices in Metro Vancouver have been much more expensive than Calgary, Edmonton, or Montreal for quite a long time, and yet they’ve gotten more expensive since then. Why do we think that would change?

To me it’s like an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object. We have a mismatch between housing and jobs. People are always moving to Vancouver because the jobs are here. At the same time, because we fear the unknown effects of new housing, we make it very difficult and expensive to build more housing. Housing is like a ladder. Because we’re not building enough new housing further up the ladder, people end up moving down the ladder, creating tremendous pressure on people closer to the bottom of the ladder.

This has been aggravated by Covid (more remote work = more demand for residential space).

The primary obstacle here isn’t physical or economic. It’s political: our system is set up to require discretionary approval of individual projects at the local level, which is slow and difficult.

I think there’s basically two possible outcomes:

Optimistic: We figure out how to make it legal (“by right”) to build a lot more multifamily housing, without having to go through a slow and painful negotiation with city hall. And we build a lot more housing over the next 10 years - CMHC estimates that we need to build at about 2.5X the business-as-usual rate to get back to 2003-2004 levels of affordability.

Pessimistic: We don’t figure it out, and people move to Calgary and Edmonton, just as people in California have been moving to the Sunbelt because housing is so much cheaper there.

I was really struck by Matthew Yglesias’s comment that 10-15 years ago, people in the US were really pessimistic about being able to fix the problem of housing scarcity.

The people from whom I first learned the substance of the land use issue were basically defeatists. Their view was that exclusionary zoning was bad, and that it contributed to an affordability crisis and to segregation, but that it also had a deep and fundamental logic to it. Homeowners benefit from scarcity and strong local veto, homeowners care a lot about land use issues, and elected officials are highly responsive to homeowners — they saw exclusionary zoning as an essentially unavoidable fact about the world.

How this changed:

What really led to bigger change, though, was a point that Yale Law School professor David Schleicher pressed on me and others during these early days — it matters where you do the politics. And in this case, it made more sense to take the fight to state legislatures rather than city councils.

The counsels of futility missed the fact that bad land use regulations aren’t a strict transfer from renters to homeowners. They also destroy an incredible amount of economic value by inhibiting capital formation, limiting agglomeration, and forcing all kinds of inefficiencies throughout the system. The gains to incumbent homeowners simply aren’t large enough for it to make sense for them to be able to block change.

The real issue is that the upsides to housing growth accrue across a city, a metro area, or even a state, while the nuisances of new construction (parking scarcity, traffic, aesthetic change) are incredibly local. So if you ask a very small area “do you want more housing or less?” a lot of people will say that they think the local harms exceed the local benefits, and the division will basically come down to aesthetic preference for more or less density. But if you ask a large area “do you want more housing or less?” the very same people with all the same values and ideas may come up with a different answer because they internalize a much larger share of the benefits.

Today the US has a lot of politicians at the state and municipal levels pushing for more housing, with numerous state-level measures in California and elsewhere. We're certainly headed in that direction in BC. In the Vancouver municipal election, the housing-skeptical party (TEAM) got only 10% of the vote. The new NDP premier, David Eby, is very pro-housing.

If we can get past the political obstacle, there’s no physical barriers stopping us from building more apartments, as Senakw demonstrates. They’re like cars: if we need more, we can just build more. As recently as 2013, Kerry Gold was reporting the lamentations of condo owners that condo prices had been stable or declining (after inflation) for the previous five years. This exactly what we want: a situation where there’s so many apartments available for rent or sale that prices decline.

Mr. Hynes paid $182,000 for his condo [five years previously], which was $7,000 below the asking price. He was thinking of selling the unit until he saw that his neighbour on the same floor, with the same suite, has just listed for $179,000.

"I thought it would at least keep its value, so I'm surprised," Mr. Hynes says. "If it had kept its value, I definitely would have sold right now."

He says his work colleagues, friends and relatives are facing the same situation. His cousin just sold her condo after renting it out for five years, and she lost money on it.

"It was for the exact same reason I'm losing out," Mr. Hynes says. "Because there are so many condos in the area."

There are too many new condos. Since the economic slump of 2009, condo starts have been on the rise, and above the 20-year average ratio of starts-to-population growth. Developments were going up almost as if it were 2007 again.

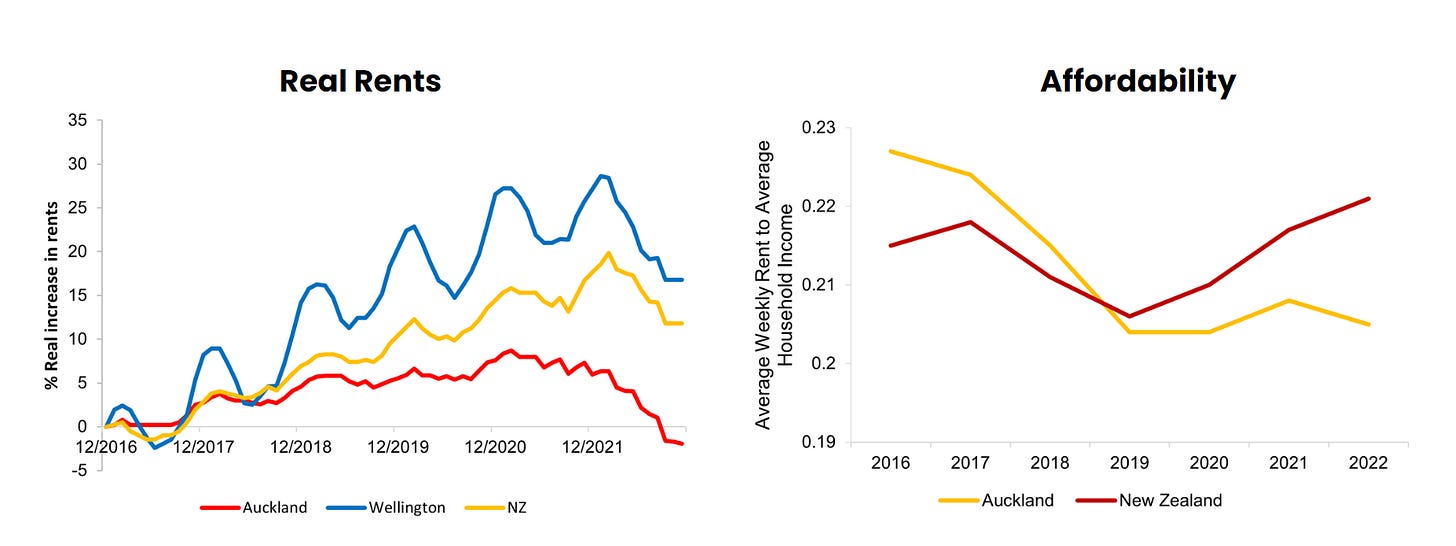

Of course not everyone wants to live in a high-rise, and high-rise projects also take a long time to plan and build. So “gentle density,” allowing multiple homes to be built on a single residential lot, is also really important. This was a big part of the Auckland upzoning in 2016, which was successful in lowering real rents and improving affordability over just five or six years.

Another great post. I really hope the policy analysts at the Ministry of Housing in the BC gov are reading your work. If I was there, I would be.