Patrick Condon thinks Vancouver doesn't need more market housing

What's wrong with his analysis?

Mario Polese, The Wealth and Poverty of Regions (2009):

As in medicine, the essential first step to a cure is an accurate diagnosis. And as in medicine, a proper diagnosis requires combining an understanding of general laws with an understanding of the patient’s particular circumstances.

Prices reflect scarcity. In the case of housing in Metro Vancouver, high prices and rents are a strong signal that we need to build a lot more housing. Because we don’t have enough housing (vacancy rates are near zero), prices and rents have to rise to unbearable levels to force people to give up and leave, matching the people remaining to the limited supply of housing. That’s why housing costs are completely decoupled from local incomes.

As a layperson, my understanding is that this is the view of all mainstream economists.

For an explanation of urban land economics, see Order Without Design (2018), by the urban planner Alain Bertaud, who has worked with many urban economists over the course of his long career. For a concise summary, see the appendix of The Affordable City (2020), by Shane Phillips.

For a review of the evidence that supply affects affordability, see Supply Skepticism: Housing Supply and Affordability, by Vicky Been, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine O’Regan, August 2018.

Alain Bertaud, describing how he first learned about urban economics from meeting Jim Wright in 1974, after having worked for nearly a decade as an urban planner:

It was my first encounter with an economist, despite my several years of urban planning practice. My degree in architecture and urban planning from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris had taught me that a city was to be designed just like a building - only the scale varied.

During my professional practice I had observed patterns in the ways that cities were spontaneously organized. Land prices decreased as one got further away from city centers. When land prices were high, households and firms consumed less land, and as a consequence, population density increased. While the objective of urban planning regulations was nearly always to limit densities, I noticed that they had very little success in doing so when the price of land was high compared to household income.

These were personal observations on the relationships between densities and prices. I did not know that a rich theoretical and empirical literature on the subject helped explain, with the help of simple mathematical models, why those patterns emerge spontaneously.

Some readers might think that I may have been an exceptionally ignorant urban planner. I do not think that I was exceptional: I was rather typical in my ignorance. In the planning profession, high land prices are often deplored but are usually thought to be caused by speculators. To this day, few planners make a connection between land prices and rents, and the supply of land and floor space. That is why planners who design regulations that severely limit the extension of cities (e.g., through measures such as green-belts, designations between urban and agricultural land, etc.) are often surprised by increasing land prices and attribute them to external factors for which they were not responsible.

In the case of Metro Vancouver, we do have a greenbelt (the Agricultural Land Reserve, shown in light green), but the main factor limiting buildable land is geographic limitations, in the form of the ocean and mountains. Restrictions on height and density near the centre (in the city of Vancouver) are like pushing down on a balloon: people don’t vanish, they move further out, driving up land prices in Burnaby, Surrey, and Langley. Alain Bertaud on Vancouver.

Patrick Condon as an example of supply skepticism

Patrick Condon, an urban planner who is now a professor at UBC’s school of architecture, is a well-known supply skeptic.

Both Don Davies and Colleen Hardwick rely on Condon’s analysis; this illustrates how housing cuts across the usual left/right divide. (Conversely, everyone from David Eby to Sean Fraser to Pierre Poilievre is pushing for more housing, based on the diagnosis that we have a severe housing shortage.)

Mainstream economists and Patrick Condon can’t both be right. Sometimes a contrarian is right (like Galileo), but often it turns out that they just don’t understand the basics.

What’s wrong with Condon’s analysis?

Getting cause and effect backwards

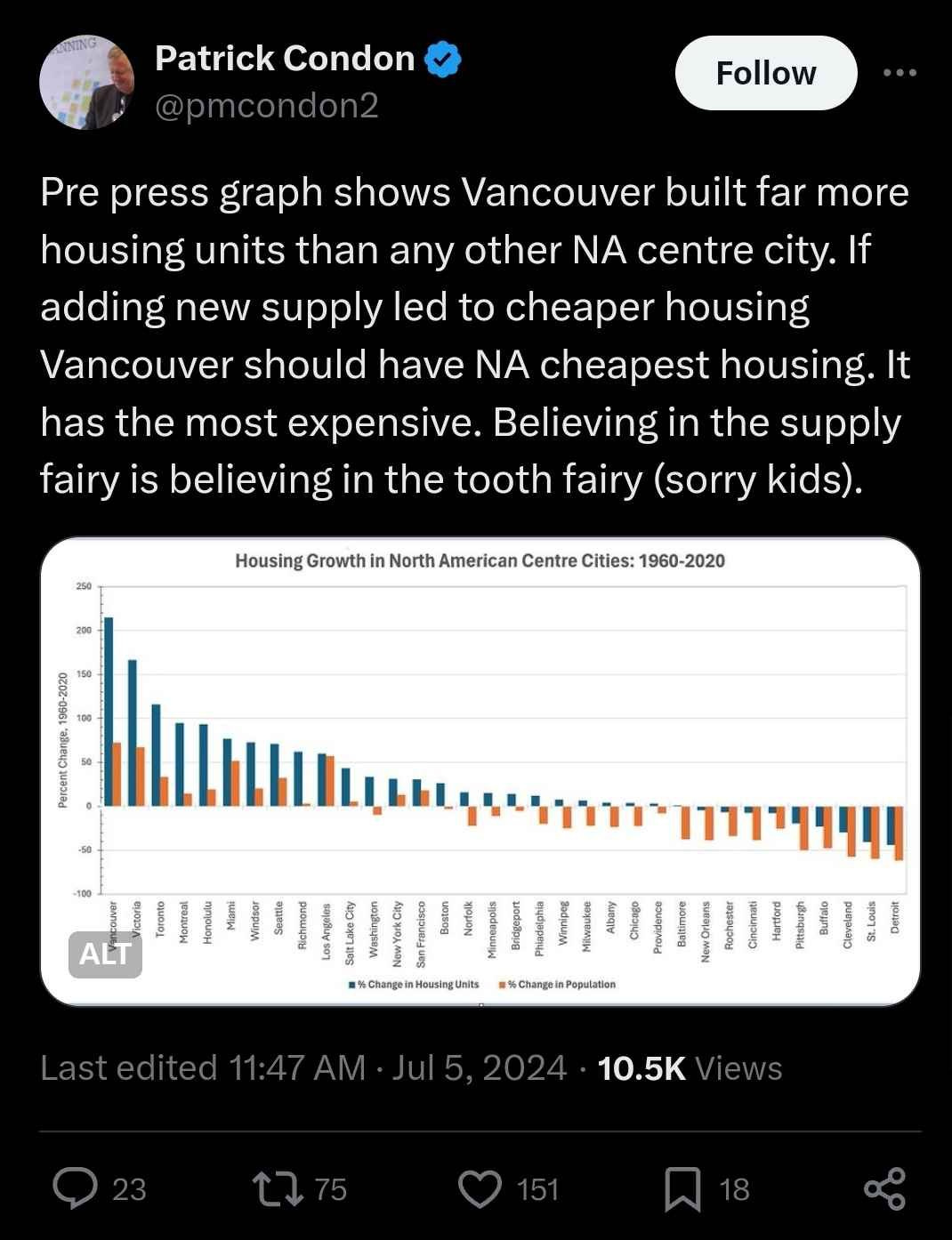

Condon argues that Vancouver's built a ton of housing, and yet Vancouver is super-expensive.

This is getting cause and effect backwards. It's like seeing people carrying umbrellas, seeing that it's raining, and concluding that umbrellas cause the rain. What's happening is that we don't have enough housing, this drives up prices and rents, and high prices and rents are a strong incentive to build more housing.

In other words: Vancouver is super-expensive, that’s why we build as much housing as we do. In fact the city of Vancouver is growing much more slowly than other Metro Vancouver municipalities, as restrictions in Vancouver push development out to Surrey and other municipalities:

The perspective of a lawyer rather than a judge

Condon’s claim above is easily interpreted as saying that Vancouver has built more housing per capita than any other city in North America. In fact his comparison is only between “centre cities,” which appears to be a category of his own invention.

Looking at housing permits, you can see that Edmonton, for example, builds a lot more during booms. In fact if you look at population growth for Canadian metro areas - closely related because people live in homes - Metro Vancouver doesn’t even make the top ten.

Condon is often accused of “cherry-picking.” I’d put it differently: he argues like a lawyer (looking for evidence to support his argument) rather than a judge (weighing the evidence for and against). If you combine the natural human tendency towards confirmation bias with the Internet, it’s easy to end up convinced of nearly anything.

William James:

The observable process which Schiller and Dewey particularly singled out for generalization is the familiar one by which any individual settles into new opinions. The process here is always the same. The individual has a stock of old opinions already, but he meets a new experience that puts them to a strain. Somebody contradicts them; or in a reflective moment he discovers that they contradict each other; or he hears of facts with which they are incompatible; or desires arise in him which they cease to satisfy. The result is an inward trouble to which his mind till then had been a stranger, and from which he seeks to escape by modifying his previous mass of opinions. He saves as much of it as he can, for in this matter of belief we are all extreme conservatives. So he tries to change first this opinion, and then that (for they resist change very variously), until at last some new idea comes up which he can graft upon the ancient stock with a minimum of disturbance of the latter, some idea that mediates between the stock and the new experience and runs them into one another most felicitously and expediently.

... Loyalty to [existing beliefs] is the first principle - in most cases it is the only principle; for by far the most usual way of handling phenomena so novel that they would make for a serious rearrangement of our preconceptions is to ignore them altogether, or to abuse those who bear witness for them.

Let’s build affordable housing by taxing new housing

Condon’s prescription is for Vancouver to require new housing to include 50% below-market housing, as a form of in-kind tax.

I don’t think he’s done the math.

Vancouver's already taxing new housing like a gold mine. Over the 10 years from 2011 to 2020, the city of Vancouver extracted $2.5 billion in supposedly-voluntary Community Amenity Contributions from new housing.

There's no such thing as a free lunch. What happens is that these increased costs are first absorbed by land lift (in the form of lower land prices), but when that's mostly gone, projects have to wait for prices and rents to rise. So then they end up getting paid by homebuyers and by renters, for both new and existing housing (since they compete with each other).

What this looks like for a six-storey rental project in East Van, as of May 2022. In order for a project to make sense, the value of the new building minus all the costs of building it has to be worth more than what's already there. That's the green part. When that's gone, nobody's going to replace existing buildings with something that's worth less.

There clearly isn't enough land lift to build 50% non-market housing. And both construction costs (red and turquoise) and single-family house prices (blue) have gone up since then, squeezing the land lift from both sides.

Other comments

When land use is very restricted (not allowing much height and density) in a high-demand city, the cost of floor space rises. And then land prices rise, despite the restrictions, because the opportunity cost is high.

If you have a parcel of land with an old house on it, and you can tear down the old house and build a new house, the value of the land will basically be the value of the new house minus the cost to build it.

The result is that where land use is very restricted, property values are primarily the cost of the land.

You can reduce the cost of land per square foot of floor space by allowing more floor space over a broad area, as Auckland did in 2016. With a broad upzoning instead of a spot upzoning, landowners can’t get much of a premium, because there’s so many other land parcels that are the same. See Shane Phillips, Building Up the "Zoning Buffer": Using Broad Upzones to Increase Housing Capacity Without Increasing Land Values, 2022.

More

Patrick Condon appearing before the Parliamentary standing committee on finance, in Ottawa, on June 13. He appears to have been invited by Don Davies, who quotes his work.

Patrick Condon Says This Is Why Housing Costs Are So High, Tyee, July 19. An exchange between David Beers and Condon. Condon writes regularly for the Tyee.

2023 Journalists Forum: Innovations in Affordability, Jon Gorey and Anthony Flint. Summary of a November 2023 conference at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy; Condon was on one of the panels. Articles by Josh Stephens and Noah Harper.

Condon’s most recent book is Broken City, published by UBC Press. The first chapter is available online. Reviews by Richard Harris and Setha Low. Summary by Douglas Todd. Interview on CBC Radio’s On the Coast.

This is one of the best explanations I have seen on this complex subject. Thanks for writing it, it's a great reference. Especially about the impossibility of adding a 50% affordability component to new developments. I do this math all the time in real life situations and clearly Mr. Condon and many of his other colleagues in academia do not know the math. You can't even build affordable housing in Vancouver today with FREE land. Maybe 5% BMR might just work, but it still creates a tax on renters (those unlucky renters who are paying full market rent are effectively subsidizing affordable rentals in new buildings). Getting off topic, but surely affordable rentals should be in older buildings (eg. the rental protection fund, which buys older rental buildings to preserve affordable rentals, seems like a better idea, and more fair to renters).

Thanks for putting in all that work, but, really, you had me at the first mention of supply and demand. Honestly, it feels like a trick question!