Mario Polèse on the natural size of urban centres

What does this mean for Vancouver?

Mario Polèse, The Wealth and Poverty of Regions: Why Cities Matter (2010). Describes economic and geographic factors in the size of cities.

Mario Polèse, The Wealth and Poverty of Cities: Why Nations Matter (2019). Despite the very similar title, this is an entirely different book, describing political and contingent factors in the size of cities.

Metro Vancouver has a mismatch between jobs and housing. It’s easy to add jobs, but difficult to add housing. The result is that prices and rents have to rise to unbearable levels to force people to leave.

In The Wealth and Poverty of Regions, Mario Polèse (a well-regarded expert on regional and urban economics) describes how urban centres have a kind of natural size. For example, when the Austro-Hungarian Empire was dismantled after World War I, Vienna’s market suddenly shrank:

Vienna presents the opposite case: an old capital whose empire suddenly shrunk as a result of border changes. In 1919, after the fall of the Austria-Hungary, the newly created Austrian Republic, a mere fraction of the old empire, found itself saddled, so to speak, with a capital that was too big for its needs. The expression at the time was Wasserkopf (loosely translated as “bloated head”). The young republic did not know what do with the huge ministries and hordes of civil servants it inherited from the defunct empire. Firms based on an internal market of 50 million, which had suddenly shrunk to 6 million, were forced either to close down or to downsize. The predictable outcome was a city whose population ceased to grow. Greater Vienna’s population today is still below that of 1910, the last census before World War I. Vienna is an example of cities adjusting to the size of their natural market areas, which are often defined by borders, be they political or cultural.

Why large urban centres exist

Polèse describes a number of factors pushing towards concentration of economic activity in urban centres:

Economies of scale in production and trade. When there’s large fixed costs, it makes sense to centralize production and sell to a large market. There’s also fixed costs in transportation: when you’re sending a truck from one city to another, the cost of the driver and the cost of operating the truck are the same whether the truck is full or half-empty.

Falling transport and communication costs. Falling transport costs mean that centralized production can reach a larger market. The same is true for communication: with radio, TV, and the Internet, news and entertainment is centralized in New York, Los Angeles, and London.

The benefits of proximity. These include face-to-face communication, the need for small specialized firms and rapid changes in production, and the ability to share the cost of specialized infrastructure.

The benefits of diversity. For firms which have constantly changing needs, like advertising agencies and management consultancies, each contract is different and requires the ability to put together a new combination of specialized talents. “Each advertising campaign is unique, requiring a unique mix of abilities and skills. One contract may call for animated cartoons, another for a symphony orchestra and jazz singer, while yet another may require trained chimpanzees. All need to be available on short notice. No management consulting contract is exactly like another. One may call for know-how in copper smelting, another for skills in management-labor relations, while yet another may require a knowledge of the intricacies of glass-blowing.”

Central location. “Firms naturally seek to locate in the geographic center of the markets, notably those for which access to customers is a primary criterion for success, most often service industries. In such cases, the most strategic location for a firm is one that minimizes travel costs for (or to) the maximum number of customers.”

Why small and medium-sized cities exist

But there’s also factors pushing in the opposite direction. Firms which are more sensitive to the costs of being in a large urban centre - high land costs, higher wages, and traffic congestion - will tend to move to smaller centres.

For some, the higher land and labor costs in the capital will outweigh the potential benefits of size. A firm requiring a great deal of space—an automobile assembly plant, for example—will give relatively more weight to land prices than a consultancy, which requires less floor space. The consultancy, in turn, will put a greater weight on face-to-face contacts with clients than would the auto plant. The auto plant would, on the other hand, put a higher relative value on the accessibility of road and rail infrastructures and the availability (and cost) of skilled blue-collar workers.

In The Wealth and Poverty of Cities, Polese describes the cluster of “midtech” manufacturing in Drummondville, about 110 kilometres east of Montreal.

Most manufacturing in Drummondville is in midtech niche products we rarely think of but need no less to be produced somewhere. Three homegrown examples are Airex Inc. (which designs and manufactures dust collection and industrial ventilation systems); Jaro Inc. (which manufactures telephone booths); and Stelinex Inc. (which manufactures custom-made stainless steel wires). The town is also home to several foreign-owned plants. German-owned Siemens Corporation (electronics) established a plant in Drummondville in the 1980s, specializing in the manufacture of electric distribution panels and security plugs. The French-owned building-materials giant SOPREMA recently established its largest North American plant in Drummondville to manufacture polyisocyanurate insulation boards. Both of these plants are located in Drummondville, but their Canadian administrative offices and distribution facilities are located in the greater Montreal area.

The lesson from Drummondville is that the efficient realization of the full production process from conception and manufacture to marketing requires different locations with different attributes, which is why small cities exist. Some things are more efficiently done in smaller places. Why assemble telephone booths or fabricate bathroom tissues in a big city where labor and real estate costs are higher, not to mention constant traffic congestion, when both can be produced more cheaply in a smaller city? The nation as a whole gains if these two goods are produced outside big cities.

Smaller centres also provide services which depend on face-to-face interaction, and which don’t require a large market:

The less distance the consumer is willing to travel, the closer the service provider will need to be to customers. Services for which proximity is vital—food stores, pharmacies, tailors, eating and drinking places, primary education, basic health care, etc.—will give rise to numerous small centers. Services that require larger markets and for which consumers are inclined to travel greater distances will only be found in larger service centers. These are normally services that are less frequently consumed or entail large household expenditures—fashion clothing, bookstores, specialized medical care, postsecondary education, etc.

Small and middle-sized towns and cities will exist as long as the consumption of services requires a physical presence. Travel takes time and money, especially time. Indeed, it can be argued that the true cost of travel has increased, since people place a higher value on time in richer societies.

Continental scale

Polèse describes the basic economic geography of Canada as being unidirectional, with economic activity concentrated in the largest urban centres (Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver) closest to the US, with the exception of Alberta.

Why are the largest European cities smaller than the largest American ones?

Urban concentrations will be larger where there are fewer barriers to trade and, more importantly, to the movement of people. Recall my earlier comments on the linguistic unity of the United States. Indeed, abstracting from the French-speaking parts of Canada, the U.S. and Canada constitute a largely homogenous cultural space, with no barriers to movement within the United States—which after all accounts for 90 percent of North America’s population north of the Rio Grande—and until not too long ago fairly open borders with Canada. Larger cities emerged because nothing stopped people from moving there. The forces of agglomeration operated freely without hindrance, and still do. Europe has smaller cities because its nations, within which people move freely, are smaller.

Why does North America have a second large concentration of economic activity on its West Coast, unlike Europe?

The West Coast of North America found itself facing dynamic trading partners on the other side of the Pacific, beginning with the emergence of Japan in the late nineteenth century, followed since by the rise of the Korean, Taiwanese, and now Chinese economies. If current trends continue, and there is little reason to believe they should not, east Asia will soon house the world’s largest economy, surpassing that of the European Union or of North America. The ports of the West Coast are the natural points of entry (and of exit) for trade with the east Asian economies.

The relative decline of the East Coast megalopolis within North America during the twentieth century can in part be traced to the relative decline of Europe as an economic power and trading partner. From a global standpoint, New York is less well situated today than a century ago, when the only other real center of economic power and wealth lay in Europe, across the Atlantic.

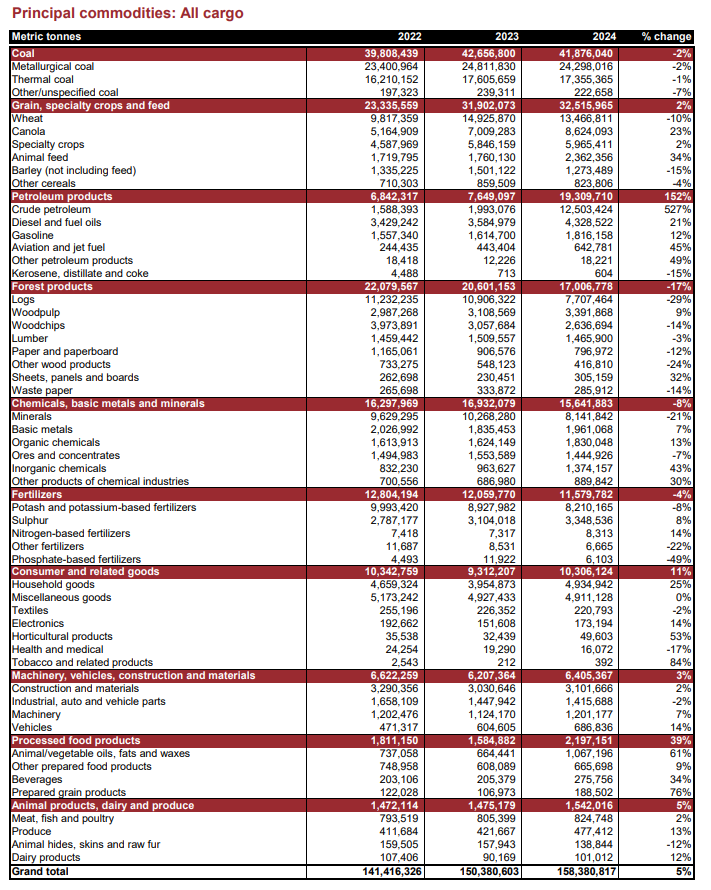

Vancouver is by far the largest port in Canada, outweighing Montreal. In 2024, Vancouver moved 158 million metric tonnes of cargo, while Montreal moved 35 million.

Given rapid economic growth in Asia, as well as ongoing disruptions in our trade with the US, we can expect Canada’s trade with Asia to continue to grow. This means we’ll need more people to expand Vancouver’s trade infrastructure, to operate it, and to maintain it. Physical assets, like roads, railways, and container cranes, wear out and break down; they require continuous effort to keep them in good working condition.

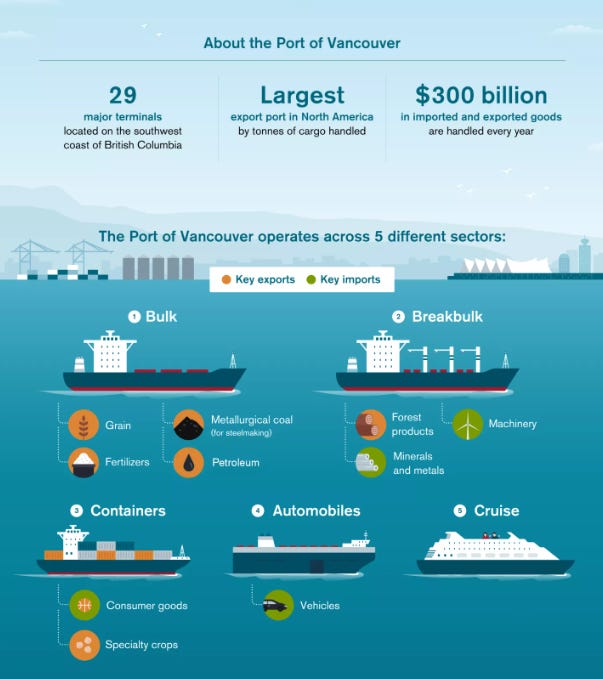

Infographic from the Port of Vancouver:

Data on the export and import cargo handled by the port:

Reviews

The Wealth and Poverty of Regions: Why Cities Matter. Pierre Desrochers, Regional Studies, September 2010.

The Mystery of Cities. Jeb Brugmann, Literary Review of Canada, September 2010.

Reviews: The Wealth and Poverty of Regions. Ablajan Sulaiman, Canadian Journal of Regional Science, 2010.

“Hollowing Out the Middle” and “The Wealth and Poverty of Regions.” David Fettig, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, November 2010.

A Review of “The Wealth and Poverty of Regions: Why Cities Matter.” Noah Ebner, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, February 2011.

Previously:

Interesting, and this bodes well for Vancouver (if you like growth), but I think there is a more important factor at play, which is climate. Both in the U.S. and Canada, the west coast has a more comfortable climate than the east coast. If ports were the main driving factor of growth, Prince Rupert would be growing rapidly, but it's not, and I blame the climate there. The biggest growth areas in the U.S. are places like Florida, California, Texas, where the climate is warmer. In Canada, it's Vancouver (and Vancouver would grow faster if housing could keep up).