Presentation on the Metro Vancouver Alliance and co-op housing

Besides work, volunteer advocacy, and political volunteering, I’m also on a couple of boards, for TRAS, a small Vancouver-based non-profit that supports health and education projects in the Himalayas; and for Or Shalom, our synagogue. (I describe my family as “Sino-Judaic”: I’m Chinese, my wife is Jewish. We’ve been members at Or Shalom since our kids were little.)

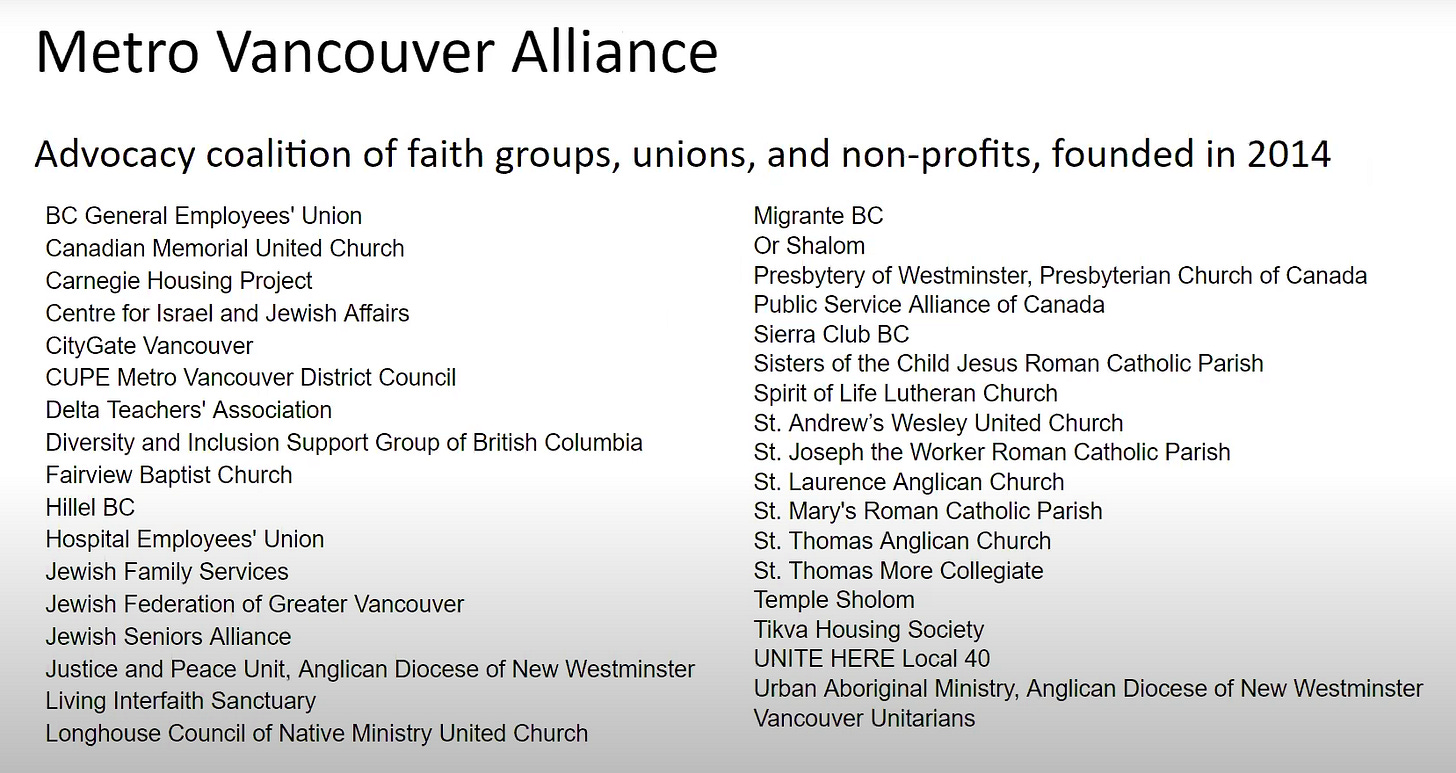

Or Shalom is a member of the Metro Vancouver Alliance, a coalition of faith groups, unions, and non-profits that does advocacy on social justice issues. MVA is currently running a campaign on housing, specifically co-op housing. Naturally I was very interested to hear this! I’ve been attending MVA meetings on behalf of Or Shalom, since January 2024.

I did a presentation on Saturday at Or Shalom on MVA’s co-op housing campaign. I didn’t use any slides, and I didn’t want to make any assumptions about what people already know about housing.

What’s going on

The problem in Metro Vancouver is that we have a mismatch between housing and jobs. People move where the jobs are. Vancouver’s a nice place to live, so a lot of people retire here. When somebody retires from a job in Vancouver, somebody else needs to move here to fill that job. Because we have an older population, we also need a lot of people to work in healthcare. And within the region, you’re going to have more people who want to live closer to the geographic centre with easy access to jobs.

Land in Metro Vancouver is limited, because of the ocean and the mountains. If you draw a circle with a 25-kilometer radius around downtown Vancouver, less than 40% of that circle is buildable land. So land in Vancouver is always going to be expensive. To add housing, we need to build up. But land in Vancouver is also extremely underused. There’s a lot of single-family houses where the land is worth way more than the building, but the city makes it illegal to build anything other than a new single-family house. So we spend a lot of time tearing down old houses and putting up new expensive houses that practically nobody can afford.

Back in the 1970s, people didn’t like the West End and they didn’t like the handful of high-rises that were going up in Kitsilano, so they made them illegal, and they set up institutions to make it hard to build new housing. To paraphrase the MacPhail Report, which is a recent report from an expert panel headed by Joy MacPhail, we regulate new housing like it’s a nuclear power plant, and we tax it like it’s a gold mine. Whenever you want to build an apartment building, you always notify everybody in the neighbourhood, as if you have to warn everyone living in the blast radius. More importantly, you need to beg the city to change the law, which is a very long and labour-intensive process. There’s a lot of micro-management. There’s a quote: “It’s easier to elect a pope than to get approval for a small apartment building in the city of Vancouver.”

The result is, as people move to Vancouver for work, prices and rents have to rise to unbearable levels to push other people out. Younger people and renters are being crushed and driven out by high housing costs.

This is a solvable problem

It’s a similar story in Toronto, or in places like California and New York City. But it’s not true everywhere. Montreal’s bigger than Vancouver, and it has cheaper housing. Edmonton’s growing faster than Vancouver, and it has cheaper housing. In the US, there’s lots of people moving from California to Texas, even though wages are lower there, because the cost of housing is so much lower.

To fix Vancouver’s housing shortage, we need to build a lot more housing, both market and non-market. We don’t have as much land as Edmonton or Texas does, so we need to build up, but we don’t need to invent some crazy new technology - elevators exist. This is a solvable problem. We have people who want to live and work here, and other people who want to build housing for them. The problem is, we don’t let them.

Co-op housing

MVA’s current campaign is focused on co-op housing.

Co-op housing is a particular form of non-market housing. With co-op housing, residents own shares in a corporation, which in turn owns the housing. It’s similar to a strata, but it’s non-profit. It’s more like owning than renting, with residents setting the budget and housing charges. It’s typically mixed-income, and often multi-generational. You have the benefit of being part of a community.

Co-ops are often on leased land. In the city of Vancouver, there’s 50 co-ops with 3700 homes on land leased from the city, with a typical lease duration of 40 years or so.

Existing co-ops in Vancouver are facing some major challenges. A number of land leases are expiring, and the city will want to negotiate new leases, based on market rates. The land leases 40 years ago were also usually market rate, but of course those rates are much higher now. This means that the land will need to be redeveloped for greater density, so that the cost of the land lease can be spread over more homes and more people.

When redevelopment happens, it’s really important to make sure that people aren’t just displaced, which is what happened at Metrotown before 2018. Vancouver has a tenant relocation and protection policy for non-market housing, with the goals being to provide a suitable replacement home that’s affordable, and to help with relocation.

Options for redevelopment

If a new land lease is negotiated and there’s a redevelopment, there’s a couple options. One is for the redevelopment to include a lot of market-rate housing, cross-subsidizing the new co-op apartments. The number of co-op apartments would be around the same number as in the existing co-op, maybe a bit more.

A second option is for the redevelopment to be 100% co-op. In that case it’s going to have a lot more height, to reduce the cost of the lease per square foot of floor space. Running a high-rise co-op is pretty different from a smaller townhouse co-op, but it’s certainly possible. There’s an umbrella organization, the Co-op Housing Federation of BC, that can provide services to co-ops, including managing them. So this is the option that MVA is pushing for. We want to make it possible for many more people to live in co-op housing.

Governments stopped funding new co-ops in the deficit-fighting 1990s, but the provincial and federal governments have now started getting back into funding co-ops. A particularly interesting program is called BC Builds. It provides low-cost construction loans for building middle-income rental housing on public land. The BC government is allocating $2B, and the federal government is contributing another $2B. This seems like a good fit for co-ops.

Another recent announcement from the city of Vancouver is that they’d like to update the city’s restrictive zoning laws to allow mixed-income social housing and co-op housing by right, so you don’t have to go through the painful process of begging the city to allow you to build housing, which you have to do for non-market housing, just like you do for market housing. In areas that already have local shopping streets, 20 storeys would be allowed. In areas that are more isolated, six storeys would be allowed. Not having to go through rezoning would cut more than a year off the typical approval process.

What MVA is doing

MVA has a committee called the Housing Research Action Team. We’ve been reaching out to various groups, including the Co-op Housing Federation and local politicians. We’d like to support the city’s initiative to allow social housing and co-op housing by right, because it’s likely to run into opposition. There’s a lot of people who say that they just don’t like expensive housing, they support affordable housing, but when you say, okay, let’s make it legal to build affordable housing, they don’t like that either.

We’re also working with local co-ops that are facing expiring land leases in the near future, to support them as they negotiate with the city. For a lot of residents, they haven’t gone through this before, and so it’s a pretty stressful process.

From the point of view of Or Shalom, working with a broad coalition of other groups has been interesting. MVA relies on face-to-face meetings, which means that it’s sometimes slow-moving, but having member organizations with a lot of people means that politicians are more likely to pay attention when you’re advocating for something reasonable.

More

Vancouver Lease Backgrounder. Co-operative Housing Federation of BC, July 2021.

I recorded a short introductory video for interested Or Shalom members on MVA and co-op housing back in September 2024.

Video by Uytae Lee (About Here) on co-op housing, from November 2022. In terms of affordability, co-op housing is similar to owning instead of renting: you’re insulated from rising costs due to increasing scarcity.

Another form of jointly owned housing is co-housing. There’s no subsidy: the group basically acts as its own developer. Co-housing runs into the same obstacles as other housing projects. Charles Montgomery describes the Little Mountain Cohousing project, which opened in 2021. We built a home to solve some of the greatest challenges of our times. “But almost nobody is following in our path. Why? Our home is illegal almost everywhere in Vancouver.”