Fighting inflation will slow homebuilding

In the aftermath of Covid, inflation is the big problem for the first time in 50 years

We're seeing a somewhat nerve-racking exercise in economic stabilization playing out in real time.

Left to its own devices, the market creates a spectacular cycle of economic booms and busts, the biggest one being the Great Depression, with unemployment hitting 25%. (Everyone's trying to save money by decreasing their spending, but one person's spending is another person's income, so it's impossible for everyone to do this at the same time.) This wasn't really resolved until World War II created massive demand.

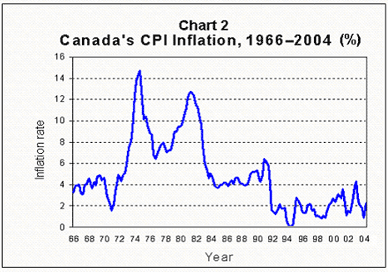

In the 1970s we ran into spiralling inflation, with wages rising in anticipation of higher prices, and then prices rising to cover wages. To get this under control, Paul Volcker at the US Federal Reserve (the central bank) used painfully high interest rates, reaching 20% in the early 1980s.

What we've settled on since then looks like this:

An independent central bank, at arms length from the government, runs monetary policy, i.e. raising interest rates to cool the economy when it's running too hot and inflation is rising, or lowering them to boost the economy when demand is low and unemployment is high. It's basically aiming to keep inflation stable, averaging 2% annually. There's no long-term tradeoff between inflation and unemployment, so this also serves to keep unemployment stable.

In addition, there's "automatic stabilizers": when the economy's in recession (shrinking) and unemployment is high, the government spends more on EI and collects less taxes. This results in a larger deficit, boosting the economy. And conversely, when the economy's booming, EI spending is down and tax revenue is up, which results in smaller deficits, restraining the economy.

When there's an unusually severe recession - like after the 2008 financial crash - and the combination of monetary policy and automatic stabilizers isn't enough (you can't lower interest rates past zero), then it makes sense to run larger deficits to keep the economy going.

After 2008, the US didn't run aggressive enough fiscal policy (due to Republican obstructionism), and so the economic recovery was grindingly slow. The Canadian economy was also running slower than usual, and so loose monetary policy (lower-than-usual interest rates) and loose fiscal policy (higher-than-usual deficits) made sense. Just before Covid, there were plenty of jobs (unemployment was low), but wages hadn't really started putting pressure on inflation yet.

Then Covid hit.

At this point, two large parts of the economy went through drastic changes. One part of the economy basically shut down: retail, restaurants, travel. People were no longer going to offices downtown, crowding into shops or restaurants, or travelling, and so a huge number of people who worked in retail and hospitality were suddenly out of work. The oil patch was also hit hard: demand for oil went through the floor, and then there was a Saudi-Russia price war on top of that.

A second part, consisting of people who could work from home, was basically unaffected, and in fact was saving huge amounts of money, since they no longer had much to spend it on.

(A third part: people in essential services - grocery stores, health care, education, manufacturing - kept working, under more stressful and dangerous conditions.)

At this point there was basically an unprecedented number of people out of work (retail and hospitality). This is why the federal government brought in CERB, as an emergency super-sized version of EI, along with a number of other income-support programs.

Given the giant wave of unemployment, people were anticipating a fall in home prices. Unexpectedly, though, what happened was that the huge surge in pandemic savings (for people who could work from home) flooded into a wide variety of asset markets, including real estate. People wanted somewhere to put their savings, and a lot of them put it into real estate. Hence the craziness of the real estate market over the last two years.

Okay, so we have unusually loose monetary policy (low interest rates) and loose fiscal policy (giant deficits), to deal with the scale of the emergency, and we have a real estate market that's going insane.

Next we had vaccine procurement and rollout, and eventually hospitalizations came down enough for the provinces to lift public health restrictions. People who were working from home are starting to return to the office.

Now the big challenge is inflation, for the first time since the 1970s. There's multiple factors here. During Covid there was a huge shift in demand from services to goods, and manufacturers didn't have enough capacity to just produce and deliver enough to meet demand ("supply chain problems"), so instead their prices went up. China is going through intermittent lockdowns. The war in Ukraine has taken a lot of oil off the market. Basically it looks like a combination of high demand and reduced supply.

At this point you need tighter monetary policy (higher interest rates) and tighter fiscal policy (lower deficits), to bring down demand to match reduced supply. We're already getting tighter fiscal policy as the emergency spending measures like CERB have expired. And the Bank of Canada has also been raising interest rates. I think it's commonly accepted that both the Federal Reserve in the US and the Bank of Canada should have started raising them earlier - Lawrence Summers makes this argument, for example - but so far, investors seem pretty confident that the central banks can get inflation under control. (Long-term inflation expectations are "anchored," i.e. they're a bit higher than usual but haven't taken off.)

Impact on housing

The problem we’re facing is that we need to cool down the economy, to get a better balance between supply and demand, but we also need more housing. And housing is one of the main channels through which higher interest rates cool the economy - housing is extremely sensitive to interest rates. As Paul Krugman puts it:

The Fed must hike: Inflation must be curbed, and as a practical matter, interest rates are the only game in town. Yet higher rates will operate largely by hitting the housing market — and over the longer term, one big problem with America is that we aren’t building enough housing.

Other things that would help to cool the economy, putting downward pressure on interest rates:

Fiscal tightening (lower deficit spending) - raising taxes, cutting spending, or both. This is politically difficult, but both the federal and provincial governments did it back in the 1990s (when interest payments on the federal debt had reached 30% of revenue). The more cooling comes from fiscal tightening, the less cooling is required from monetary tightening.

Supply-side reforms - looking for ways to improve productivity in the medium term, for example by identifying regulations that no longer make sense in when the economy is suffering from scarcity rather than inadequate demand.

Matthew Yglesias describes the need for supply-side reforms: “The right way to think about it is that the economy is either suffering from depressed demand or it isn’t. If it is, you should fix that. But if it isn’t, the only path toward growth is a steady drip drip drip of supply-side improvements. We hope that a lot of that will come from innovation and new technology. But it can also come from steadily improving public policy.”

A good example: Mike Moffatt on tariff reform, 2016.

A couple more implications:

In the city of Vancouver, we may have missed the boat on rental housing. Rental projects were economically viable when interest rates and “cap rates” were low, and the city should have approved a lot more of them. We often seem to take it for granted that people want to build housing in Vancouver.

Just as the mortgage stress test was a way to tighten credit for housing specifically without slowing down the economy as a whole, programs like RCFI (which provides low-cost long-term loans for building rental housing) would be a way to improve the economic viability of rental projects while still cooling the overall economy.

When there’s a slump in homebuilding, that would be a good time for countercyclical public investment in housing: public projects won’t be competing with private projects for labour and materials in a red-hot market. But offsetting the fiscal stimulus will require raising taxes or cutting spending elsewhere, which is politically difficult.

Related:

In a 1997 article, Paul Krugman explains monetary policy, how the central bank raises or lowers interest rates to keep the economy from being either too hot (high inflation) or too cold (high unemployment). “The simple Keynesian story is one in which interest rates are independent of the level of employment and output. But in reality the Federal Reserve Board actively manages interest rates, pushing them down when it thinks employment is too low and raising them when it thinks the economy is overheating.” Janet Yellen provides a similar explanation in a 1995 interview.

Noah Smith explains why people dislike periods of inflation - it usually results in lower real incomes.

Canada’s Balancing Act. A data-driven analysis from Joseph Politiano.

We Need to Keep Building Houses, Even if No One Wants to Buy, August 2022. New York Times article on the slowdown in homebuilding and the longer-term shortage of housing.

Project cancellations during Canada's housing downturn will worsen affordability, July 2022. Daily Hive article based on a CIBC bulletin. “In the GTA alone, out of 30,000 condominium homes that were supposed to be launched in 2022, at least 10,000 have already been cancelled or put on hold, according to Urbanation.”

“Deal Killer”: Developers Grow Wary, Pause Projects, as Interest Rates Rise. Kerry Gold, November 2022. Discusses government funding for rental housing, including RCFI and MLI Select.