Joseph Heath describes taxation and public spending as a form of collective shopping. For some goods (food, clothing) it makes no sense to buy them collectively. For others (roads, insurance) it does make sense. From Filthy Lucre (2009):

So if Canadians want to consume more health care or a new subway or better roads, what are their options? The situation is the same as with condo residents who want a new sauna: If people want to buy more of this stuff (and are willing to buy less of something else), then they should vote to raise taxes and buy more of it. It doesn't necessarily impose a drag on the economy to raise taxes in this way, any more than it imposes a drag on the economy when the residents of a condo association vote to increase their condo fees.

One can see, then, the absurdity of the view that taxes are intrinsically bad, or that lower taxes are necessarily preferable to higher taxes. The absolute level of taxation is unimportant; what matters is how much individuals want to purchase through the public sector (the "club of everyone"), and how much value the government is able to deliver. This is why low-tax jurisdictions are not necessarily more "competitive" than high-tax jurisdictions (any more than low-fee condominiums are necessarily more attractive places to live than high-fee condominiums).

Furthermore, the government does not "consume" the money collected in taxes - this is a fundamental fallacy; it is merely the vehicle through which we organize our spending. In this respect, taxation is basically a form of collective shopping. Needless to say, how much shopping we do collectively, and in what size of groups, is a matter of fundamental indifference from the standpoint of economic prosperity.

Matt Gurney observes that our cities have a large and growing “state of good repair” deficit. In short, we’re not spending enough money to maintain our infrastructure, because we’re not willing to pay enough property taxes to do so. In the city of Vancouver, for example, the city’s own budget notes that we need to spend about $800M per year to maintain our infrastructure in a state of good repair. Our actual spending is $500M.

I think there’s a general problem: instead of paying more taxes, we look for ways to get someone else to pay the bill. But there’s no such thing as a free lunch: this often has bad side-effects. Three examples: development charges, oil royalties, international-student tuition fees.

Development charges

On the housing policy side, there's currently a fight over municipal development charges. Basically, the housing shortage in Metro Vancouver and the GTA is aggravated by municipalities taxing new housing like it's a gold mine. Naturally, senior levels of government are saying, "Don't do that." Problem is, you can't beat something with nothing: municipalities are underfunded, they have a hard time raising property taxes (they're extremely visible and thus unpopular), and so they've resorted to taxing new housing instead.

In a high-trust environment, a better solution would be to lower taxes on new housing and pay for new water and sewer infrastructure (the most expensive part of it) with long-term bonds, paid down over time from full-cost water usage fees. A 2014 blueprint along these lines, from Frank Clayton at Toronto Metropolitan University’s Centre for Urban Research. Benjamin Dachis at C. D. Howe has commentaries making similar arguments going back to 2018: Stop hosing homebuyers.

But in a low-trust environment, nobody wants to see their property taxes or utility fees go up. So instead Vancouver and Toronto are strangling themselves by taxing new housing like a gold mine (and regulating it like a nuclear power plant), and when Covid hit, housing scarcity spilled over to the rest of the country, spreading misery everywhere.

Oil royalties

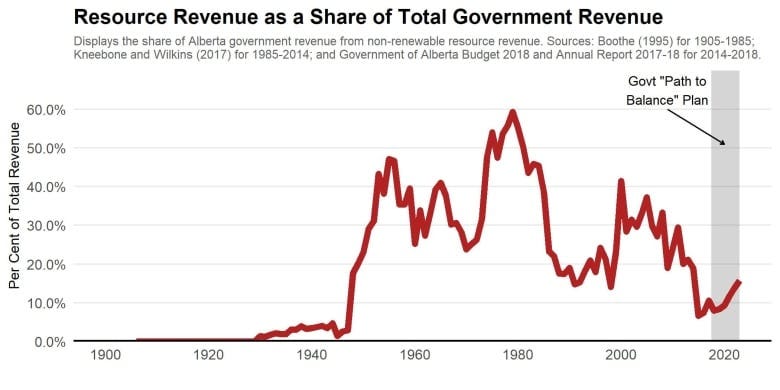

A second example of governments turning to other sources of revenue because of resistance to taxes: Alberta's reliance on oil royalties, tying it to the oil-price rollercoaster. See the Emerson Report, or Trevor Tombe’s commentary in November 2018.

Joseph Heath's sardonic comment about the connection between natural resource development and conservative low-tax politics: "Under this scenario, we just keep on digging up bitumen and selling synthetic oil, investing in new mines, processing and pipeline infrastructure, subject to absolutely no constraints and a carbon price of zero. And people don’t have to pay taxes, because, yay! we’re digging money out of the ground."

High international student fees

A third example is the post-Covid international student boom, especially at Ontario colleges. High international student fees were an attractive way for the Ontario government to fund post-secondary education. Ontario colleges get more funding from international student fees than from the Ontario government and from domestic tuition combined; their incentive is to bring in as many students as possible, using third-party recruiters who have no reason to consider things like educational quality or housing availability. The federal government is now hitting the brakes hard, cutting this lucrative source of revenue.

Tax increases require trust

In all three cases, we have a gap or deficit between the services we want and the taxes that we're willing to pay.

I think this is really aggravated by low levels of trust, which in turn is driven by changes in the technological and communications environment. So then we end up with underfunded institutions that spend a lot of time on communications (trying to keep things from going viral, or even worse, dealing with a story that's gone viral) instead of service delivery.

Great post.

I'm doubtful about one thing though: a link between trust and residential property taxes. Evidence against:

* Compared to other countries, Canada already has relatively high levels of trust and taxes.

* Denmark and Norway have much higher self-reported trust than Canada, but a cursory Google search shows that residential property taxes in their capitals are comparable to those of Canadian cities.

* Vancouver property owners have successfully been lobbying for lower taxes for over 100 years. Is social media really making this worse?

(I'm not especially knowledgeable about this topic, just sharing my reaction)