Speaking notes for HUMA parliamentary committee

The importance of reducing costs

The Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities (HUMA for short) is doing a study on homelessness and funding for non-market housing. They invited me to appear as a witness on Monday, along with Eric Lombardi of More Neighbours Toronto, and Leah Zlatkin, a mortgage broker.

Unfortunately I won’t be able to share slides via Zoom (you’re not allowed to use props), but I’ve included some visuals below.

Hi, my name is Russil Wvong. I’m a volunteer with Abundant Housing Vancouver. I don’t work in development or in policy - I just read all the reports. I’d like to talk about three things.

Against defeatism

First, the housing shortage is a problem that’s fixable. In Texas, Austin is building so many apartments that rents have dropped 12% in one year.

In Vancouver, we have people who want to live and work here, and other people who want to build housing for them. The problem is that the approval process is extremely slow: “It’s easier to elect a pope.”

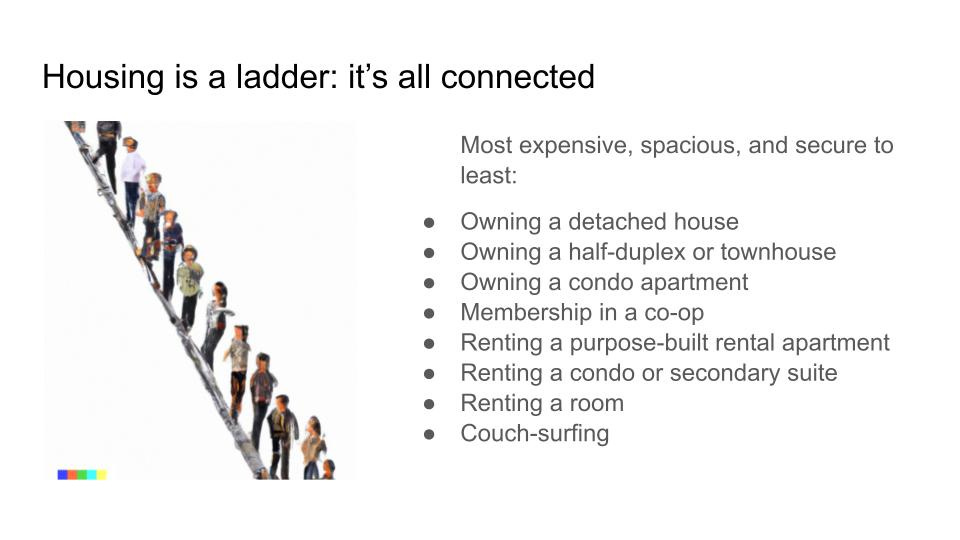

Housing is a ladder - it's all connected. Whenever we block market housing that somebody wants to build, the people who would have lived there don't disappear. They move down the housing ladder, competing with everyone else for the limited supply of existing housing. Prices and rents have to rise to unbearable levels to force people out. We get trickle-down evictions.

In Metro Vancouver, the result is a housing shortage that’s bad for everyone, terrible for younger people and renters, and worst of all for people near the bottom of the housing ladder. They're forced to move away, to crowd into substandard housing, or end up homeless.

The Covid spillover

Second is Covid. Housing being painfully scarce and expensive is no longer a problem confined to Toronto and Vancouver. When Covid hit and there was a sudden massive surge in people working from home instead of the office, total demand for residential space went way up, while demand for office space went way down. Plus a lot of people moved in order to find cheaper housing, which was great for them, but bad for local renters and homebuyers. The housing shortages in the GTA and Metro Vancouver basically spilled over to the rest of the country.

This means we need to build a lot more housing everywhere, not just in the biggest cities, for the next 10 years or more. Our pre-Covid housing stock no longer lines up with where people want to live and work. Other countries are facing the same challenge.

Municipal fiscal capacity

Third, in the GTA and Metro Vancouver, we need to move away from taxing new housing like it's a gold mine. Over the 10 years from 2011 to 2020, the city of Vancouver extracted $2.5 billion in “Community Amenity Contributions.” The thing to remember is, there's no free lunch. Someone has to pay.

If costs are too high, what happens is that nothing gets built until prices and rents rise further, for both new and existing housing. That's exactly what's happening now. In other words, it's renters and homebuyers who end up paying for these increased costs.

The federal government has made two major changes to reduce the cost of building new rental housing, removing the GST and allowing accelerated depreciation. This will help to counter the headwinds that result from higher costs.

The problem is that local governments in Ontario and BC have strong incentives to raise development charges, slowing things down again, because they need money to meet local needs, and because it’s very difficult to raise property taxes.

The BC, Ontario, and federal governments are all pushing municipalities to slow down, freeze, or reduce development charges. But as long as local governments need the money, they’re going to push back hard. There’s a number of proposals for alternatives. Benjamin Dachis suggests paying for water and sewer infrastructure by issuing long-term bonds that are then repaid from water usage fees. Municipalities have proposed progressive property taxes, regional sales taxes, and regional income taxes. If you look at the US, they have property-tax rates that stay the same instead of being adjusted each year. So if there’s a lot of demand and property prices are rising, municipal revenues automatically go up, allowing them to build more infrastructure.

What should the federal government do?

Finally, how can the federal government convince local governments to stop regulating new housing like a nuclear power plant and taxing it like a gold mine? Unlike provincial governments, the federal government doesn’t have direct control.

Machiavelli describes the three elements of diplomacy as persuasion, promises, and threats. It’s most effective to use a combination of all three. Sean Fraser has been quite successful in using Housing Accelerator funding to convince municipal governments to allow more housing, with denial of funding as a stick to go along with the carrot.

Persuasion is also vitally important, and federal MPs from all parties can help. It’s great that we seem to have consensus across the political spectrum on the need for more housing. For example, when Calgary city council voted down its own housing task force recommendations 8-7, it was very helpful to immediately see critical comments from Scott Aitchison and Michelle Rempel Garner. It seems likely that this contributed to Calgary city council reversing its decision the next day.

Appendix: What the cost bottleneck looks like

Reducing costs is really important. Even when something is legal, if costs are too high it won’t get built. A project doesn’t make sense unless the value of the new building, minus all the costs of building it, is high enough. That’s basically how much the project can pay for land. It’s volatile, it goes up and down a lot. It has to be significantly higher than the current value of the property with its existing building, or the landowner won’t have an incentive to sell, and nothing will happen.

This graph shows an analysis by Coriolis, from May 2022, of a six-storey rental project in Vancouver. With rents at that time, the value of the new building would be about $860 per square foot, the total height on the right. The “hard costs” for labour and materials are about half of that, shown in red. All other costs, including development charges and GST, are shown in turquoise. Subtracting those costs, you get $230 per buildable square foot that the project can pay for land. The value of the land with its existing buildings is $180 per square foot, shown in blue. So that leaves $50 per buildable square foot in “land lift” that motivates the landowners to sell, shown in green.

As costs rise, the green part shrinks. When it’s too small, the landowners aren’t interested in selling, and nothing happens until prices and rents rise enough for the project to make sense. In other words, cost increases are first absorbed by land lift, but once that’s gone, they end up being paid by homebuyers and renters. It doesn’t just affect prices for new buildings, it also affects prices for existing buildings, since they compete with each other.

One final note is that you can make more projects viable by adding what Michael Mortensen calls “Vitamin D”: density. Some costs, like land, are basically fixed. You can reduce the cost per square foot of floor space by allowing more height and density, spreading the fixed costs over more floor space.

More

A similar five-minute presentation to the Metro Vancouver Regional District board, with slides.

All the lights are flashing red, all the sirens are going off. A longer briefing, with slides.

Austin: building more housing, rents falling. An email to Mayor Mike Hurley of Burnaby.

Homeowners fear change to their neighbourhood, not falling prices.