Samuel Hughes on the Great Downzoning

Were zoning restrictions driven by interests or by ideas?

Why the West was downzoned. Samuel Hughes, Works in Progress, November 2025.

Samuel Hughes on the Great Downzoning. Works in Progress podcast, June 2025, with transcript.

Samuel Hughes takes a close look at the history of zoning restrictions, starting in the late 19th century. He argues that they were driven primarily by the interests of property owners, rather than misguided ideas on the part of planners. When the interests of property owners and the ideals of planners were in conflict, it was typically the property owners who won.

That said, besides interests and ideas, there’s also a third element of politics, namely institutions. Once institutions have been created, they typically last for a long time. Hughes observes that in cities with acute housing shortages, the interests of property owners have now changed: the benefit from having the option to redevelop their property for higher density has become more and more valuable, outweighing their interest in keeping their neighbourhoods the same. But this isn’t yet reflected in our institutions.

On the mystery of the Great Downzoning:

In 1890, most continental European cities allowed between five and ten storeys to be built anywhere. In the British Empire and the United States, the authorities generally imposed no height limits at all. Detailed fire safety rules had existed for centuries, but development control systems were otherwise highly permissive.

Over the following half century, these liberties disappeared in nearly all Western countries. I call this process ‘the Great Downzoning’. The Great Downzoning is the main cause of the housing shortages that afflict the great cities of the West today, with baleful consequences for health, family formation, the environment, and economic growth. One study found that loosening these restrictions in just five major American cities would increase the country’s GDP by 25 percent. The Downzoning is one of the most profound and important events in modern economic history.

Demand for zoning restrictions

In the June 2025 podcast, Hughes describes the fear of decline:

Europeans in pre-modern times didn’t think [about older homes as heritage], they thought of them as cars or computers or something. Like you’ve got a shoddy old house which is going to have loads of defects and at some point going to require loads of expensive work. So you had the properties themselves constantly degrading, just physically. Fashion was capricious then as now, and if they’re building new suburbs, the new suburbs will be built to be maximally attractive

and try to draw people out [making older neighbourhoods less attractive]. So you have a constant tendency for neighbourhoods to fall into decline.

This is the setting of the novel The Quincunx (1989):

Everyone at this time who was middle class was terrified of their neighbourhood falling into penury and becoming a very dangerous, unpleasant place with 20 people crammed to a room. And they gave the example of the Devil’s Acre in Westminster where all the streets are lined with these crumbling grand mansions, which are now split into 20 people crammed into every room and all kind of criminality is being carried out around.

In Vancouver, presumably this was the fear that motivated attempts to preserve the West End and Shaughnessy, keeping mansions from being turned into rooming houses.

The demand for zoning restrictions originated in property owners wanting to protect elite suburbs from decline. Initially they were implemented as private covenants, but this turned out to be difficult to enforce. From the article:

Suburbia really took off internationally in the nineteenth century, when planned suburbs spread across the British Empire, the United States, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and, to a lesser extent, France. The most universal and decisive factor behind this was probably again deepening capital markets and higher rates of urban growth. Other factors – none of which applied everywhere, but all of which were important in some places – included better roads, the development of suburban railways, buses and trams, improved policing, the abolition of customs boundaries around towns, the reform of feudal land tenures, and the demolition of city walls.

Hughes describes the interests that homeowners sought to defend:

When people buy a home, they care not only about the home itself, but about the neighborhood in which it stands. This was why nineteenth-century developers started building whole villa colonies and streetcar suburbs rather than just individual houses: by developing entire neighborhoods, they could satisfy a wider range of buyers’ preferences, giving people the neighborhood of their dreams rather than just the house.

Some of the perceived advantages of low density will apply virtually anywhere, like quieter nights, greener streets, more and larger private gardens, and greater scope for social exclusivity. Other attractions are more specific to certain contexts. Where urban pollution is bad, people seek suburbs for cleaner air. Where crime is high, suburbs are often seen as a way of securing greater safety.

Restrictions on densification were a way of preserving these ‘neighborhood goods’ in perpetuity. The prevalence of covenanting constitutes extremely strong evidence that suburban people wanted this. Covenants were imposed by developers, whose only interest was in maximizing sales value. They judged that the average homebuyer valued the neighborhood goods that covenants safeguarded more than they valued the development rights that covenants removed.

Interests vs. ideas: the failure to lower greenfield density

Hughes discusses the ideas prevalent among planners (e.g. the “Garden City” ideal), but points out that when they conflicted with the interests of property owners, it was typically the interests of property owners that won out. In particular, with respect to greenfield development:

A vivid example of this is the attempt of planners to lower the density of greenfield development (new neighborhoods on previously undeveloped land). In Anglophone countries, the density of greenfield development was already fairly low by the early twentieth century, and there was not much for planners to do in lowering it further. In continental countries, however, much greenfield development still took the form of densely massed apartment blocks, which were seen by planners and officials as a shameful humanitarian disaster. Lowering these densities was widely seen as just as much of a priority as protecting existing suburbs, and in many countries it dominated public debate about zoning.

The problem was that, unlike in existing suburbs, downzoning greenfield sites generally reduced their value. Developers built dense apartment blocks because, given prevailing market conditions, that was the most valuable use of the land. Requiring them to build terraced houses or cottages instead crashed land values and annihilated the asset wealth of landowners. Planners and municipal officials thus faced a powerful special interest group, against which they had great difficulty in prevailing.

Some examples:

Planners in Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece generally shared the standard European aspiration towards lower densities, but they had few existing planned suburbs to defend: the only possible downzoning would be on greenfield land, suppressing density in new urban areas. This would run contrary to the interests of the landowners.

In all four countries, this failed to happen, and urban densities remained stubbornly high, only falling gradually in the late twentieth century under the influence of market forces.

The story was initially similar in Germany and France. German planners made strenuous efforts to downzone greenfield sites before the First World War, but met with fierce resistance from landowners. In general, the landowners were successful in preserving their right to build apartment blocks, although they sometimes had to include larger courtyards and front gardens. In France, the planning movement was much weaker, and made little progress against landowner and developer interests.

Interests vs. ideas: the failure of densification

Hughes also points out that when ideas shifted and planners supported densification, very little happened.

What happened at the end of the twentieth century is no less problematic for the planner-driven explanation of the Great Downzoning. From the 1960s onwards, the intellectual tide began to turn in favor of density, and by the 1990s, density was wildly fashionable again.

Every planning school in Britain teaches its students the importance of density, walkability, and mixed use.

But density has been concentrated in former industrial or logistics sites, in city-centre commercial areas, or in social housing, which the authorities regularly demolish and rebuild at greater densities. Towns without much of this, like Oxford and Cambridge, have stable or even declining populations in their city centres. An effort to enable more suburban densification nationally in the 2000s aroused much controversy and was soon abandoned. A more recent attempt to allow more densification in an area of South London, widely praised by planners, led to a local political revolution and the policy’s revocation.

Giving homeowners the option

So if interests are primary, what are the prospects for building more housing?

Hughes argues that where housing shortages have become particularly terrible, the financial benefits of having the option to redevelop for greater density have grown so large that they outweigh the benefits of maintaining “neighbourhood goods.” This suggests that if given the option, property owners may choose to loosen zoning restrictions and allow greater density. Hughes gives a number of examples where this has happened.

One element of the preceding argument may have puzzled some readers. I have argued that density controls were originally imposed because they increased property values, suggesting that allowing densification is net value destroying. But many housing reformers, including me, have argued that granting additional development rights to streets or neighbourhoods increases their value, for the obvious reason that the additional floorspace is worth a lot. This has been confirmed by recent examples. For example, residents of the London neighbourhood South Tottenham recently persuaded their local councils to let them double the height of their houses. All properties in the neighbourhood enjoyed an immediate boost in value once the council agreed.

In South Korea, some neighborhoods are allowed to vote for much larger increases in development rights. This generates abundant value uplift, as a result of which residents of such neighborhoods nearly always vote in favor. In Israel, apartment dwellers can vote to upzone their building: this has proved so popular that half of the country’s new housing supply is now generated this way. How can such cases be reconciled with the argument I have given here?

The answer lies in how the housing market has changed since the nineteenth century. Over the last century, in large part because of the Downzoning, housing shortages have emerged in many major cities, in the sense that floorspace there sells for much more than it costs to build. This means that the development rights lost through density controls have become steadily more valuable. At a certain point, their summed value became greater than that of the neighborhood values for which they had been sacrificed. It was at this point that they became value-destroying.

Is this correct?

Not sure.

The argument by David Schleicher is that what’s going on is a collective action problem. Hyperlocal opposition to housing is like pushing down on a balloon: it drives up prices and rents elsewhere as people are pushed further out. Schleicher’s recommendation is to move decision-making to a higher level.

The people from whom I first learned the substance of the land use issue were basically defeatists. Their view was that exclusionary zoning was bad, and that it contributed to an affordability crisis and to segregation, but that it also had a deep and fundamental logic to it. Homeowners benefit from scarcity and strong local veto, homeowners care a lot about land use issues, and elected officials are highly responsive to homeowners — they saw exclusionary zoning as an essentially unavoidable fact about the world.

... What really led to bigger change, though, was a point that Yale Law School professor David Schleicher pressed on me and others during these early days — it matters where you do the politics. And in this case, it made more sense to take the fight to state legislatures rather than city councils.

The counsels of futility missed the fact that bad land use regulations aren’t a strict transfer from renters to homeowners. They also destroy an incredible amount of economic value by inhibiting capital formation, limiting agglomeration, and forcing all kinds of inefficiencies throughout the system. The gains to incumbent homeowners simply aren’t large enough for it to make sense for them to be able to block change.

The real issue is that the upsides to housing growth accrue across a city, a metro area, or even a state, while the nuisances of new construction (parking scarcity, traffic, aesthetic change) are incredibly local. So if you ask a very small area “do you want more housing or less?” a lot of people will say that they think the local harms exceed the local benefits, and the division will basically come down to aesthetic preference for more or less density. But if you ask a large area “do you want more housing or less?” the very same people with all the same values and ideas may come up with a different answer because they [get] a much larger share of the benefits.

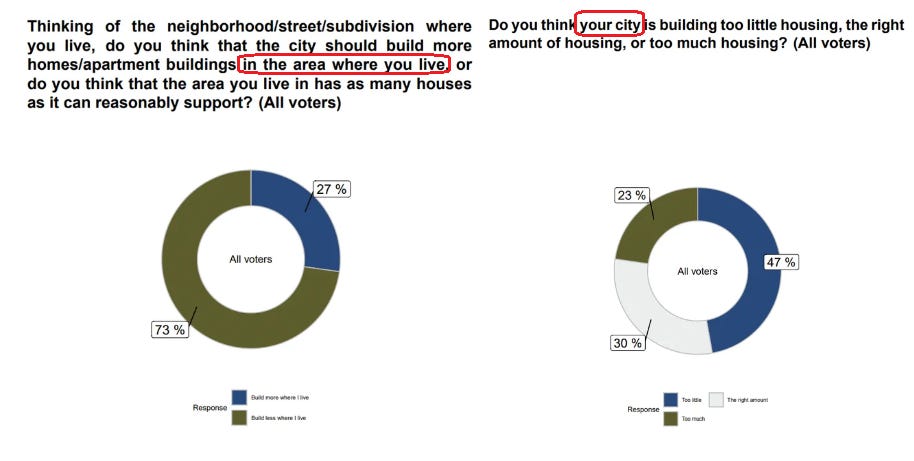

A poll of Toronto residents in May 2023:

The argument against making densification optional is that opposition increases as you get down to the hyperlocal level, and every neighbourhood would simply opt out.

The argument for making densification optional is that it serves as a kind of safety valve. As Hughes points out, the option to redevelop your property for higher density is increasingly valuable, so it’s possible that people in most neighbourhoods will be motivated to allow density. If people in specific neighbourhoods are especially opposed to change, they can opt out instead of fighting the city-wide policy.

It’d be useful to get more polling on this question.

Previously: