The Economic Implications of Housing Supply (Glaeser and Gyourko, 2018)

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.32.1.3

How house prices are determined - especially in Vancouver - is something of a mystery to me, so I took the time to read through this US paper. Some particularly interesting points:

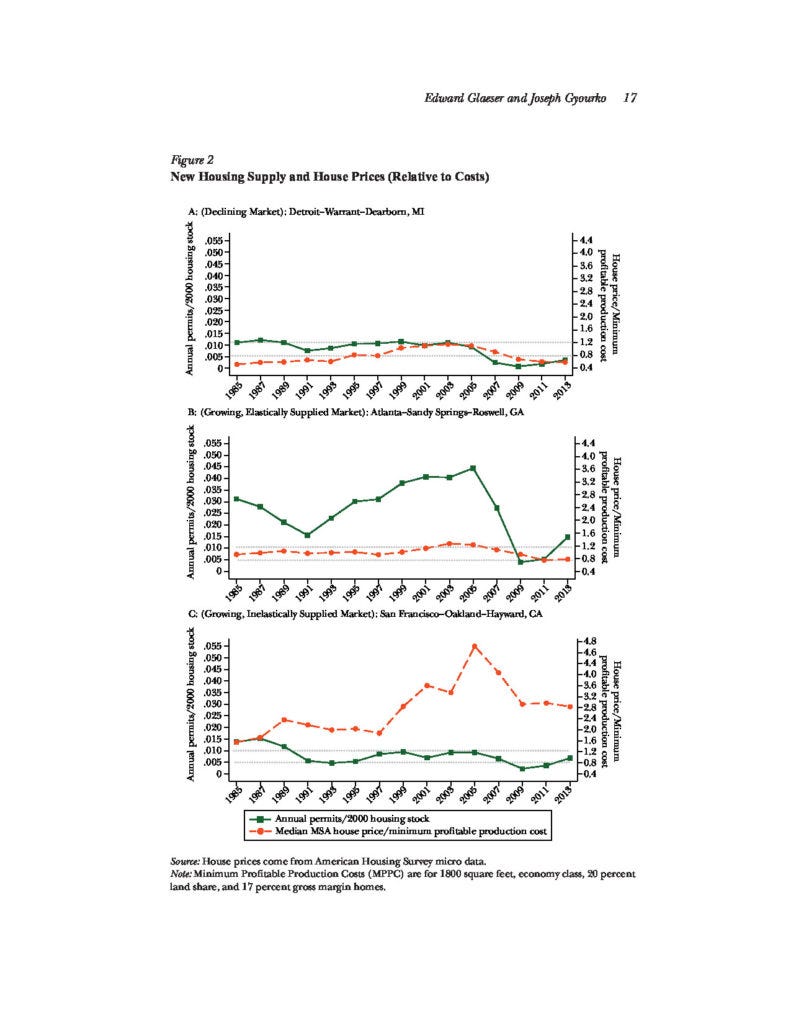

In a city like Atlanta, where housing supply is pretty responsive, you see housing starts vary a lot (sometimes up, sometimes down), while house prices are stable. In a city like San Francisco, where housing supply is inelastic, what you see is that housing starts are stuck at a low level, while house prices can rise (and fall) rapidly. See Figure 2 above.

In a city like Atlanta, house prices reflect the "minimum profitable production cost": land is about 20% of the cost, construction cost (which doesn't vary that much from one location to the next) is about 80%, and there's a 17% gross margin. "This suggests that an efficient housing market should be able to supply economy-quality single-family housing with 2,000 sq ft of living space for around US$200,000 in low construction cost markets and for little more than US$265,000 in the highest construction cost markets." (p. 10)

As of 2013, 16% of metro areas in the US had median price-to-cost ratios of over 1.25. So in most metro areas, prices were reasonable. But the high-cost areas include some of the most productive labour markets (like New York, San Francisco, and San Jose), so they have an outsize impact on the economy. (p. 14)

"This gap between price and cost seems to reflect the influence of regulation, not the scarcity value arising from a purely physical or geographic limitation on the supply of land. For example, in Glaeser, Gyourko, and Saks (2005), we show that the cost of Manhattan apartments are far higher than marginal construction costs, and more apartments could readily be delivered by building up without using more land. This and other research we have done (Glaeser and Gyourko 2003) also finds that land is worth far more when it sits under a new home than when it extends the lot of an existing home, which is also most compatible with a view that the limitation is related to permits, not acreage per se." (p. 14)

San Francisco (p. 16):

"San Francisco represents the third type of housing market in which the price of housing is considerably above the minimum profitable production cost. In this situation, strict regulation of housing construction means developers in this type of market cannot bring on new supply even though it looks as if they could earn super-normal profits if they did. Unlike the graph in Figure 1, the supply schedule beyond the kink is upward sloping" - in other words supply isn't very elastic, and as demand increases, prices rise faster than the quantity of housing.

"As Figure 2C shows, the median house price in this market has been well above the minimum profitable production cost for the past three decades and reached dramatic heights at the peak of the last housing boom in 2005. However, permitting activity did not increase at all over the eight-year span from 1997 to 2005, even though the median price-to-cost ratio increased from below 2 to over 5." High prices didn't result in much more building.

"San Francisco is a relatively high physical construction cost market, but that is not what makes its homes cost so much. The median housing unit in this market contained 1900 square feet, and the physical construction costs for this unit based on RSMeans data were $192,938, so the per square foot cost of the (presumed modest quality) structure was just over $100 per square foot, which is one of the most expensive construction cost markets in the United States. Our earlier assumption that land is 20 percent of the physical-cost-plus-land total provides an estimated land price of $48,235. Stated differently, that is what we think the underlying land would cost in a relatively unregulated residential development market. Add the builder’s 17 percent gross margin, and the minimum profitable production cost for this house is $281,690. This compares with an actual price of the median house of $800,000 (and thus a price-to-cost ratio of 2.84). Clearly, San Francisco housing developers cannot actually earn super-normal profits on the margin. Instead, what makes San Francisco housing so expensive is the bidding up of land values. Our formula suggests that the land underlying this particular modest-quality home cost about $490,000 — roughly 10 times the amount presumed for our underlying calculations of the minimum profitable production cost."

Why homeowners don't feel rich (p. 20):

"... housing wealth is different from other forms of wealth because rising prices both increase the financial value of an asset and the cost of living. An infinitely lived homeowner who has no intention of moving and is not credit-constrained would be no better off if her home doubled in value and no worse off if her home value declined. The asset value increase exactly offsets the rising cost of living (Sinai and Souleles 2005). This logic explains why home-rich New Yorkers or Parisians may not feel privileged: if they want to continue living in their homes, sky-high housing values do them little good."

Resistance to change (p. 27):

"If the welfare and output gains from reducing regulation of housing construction are large, then why don’t we see more policy interventions to permit more building in markets such as San Francisco? The great challenge facing attempts to loosen local housing restrictions is that existing homeowners do not want more affordable homes: they want the value of their asset to cost more, not less. They also may not like the idea that new housing will bring in more people."

In general, people dislike change. In Vancouver, most homeowners like their neighbourhood the way it is - that's why they live there! But if you ask everyone, support for rental apartment buildings is surprisingly high. When Burnaby ran a workshop with randomly selected residents, 70% supported four- and six-story apartment buildings in residential neighbourhoods. A poll in Vancouver found similar results. So I'm hopeful that in the medium to long term we'll be able to build enough housing (especially rental housing) to bring down housing costs.