After reading the Twitter thread below: Not to pick on Adam Vaughan, but I think that federal Liberals (including myself) need to have a serious debate within the party about housing scarcity and what the federal government can do about it. Do we want to just focus on affordable non-market housing, and leave market housing to take care of itself? Or do we want to support both market and non-market housing?

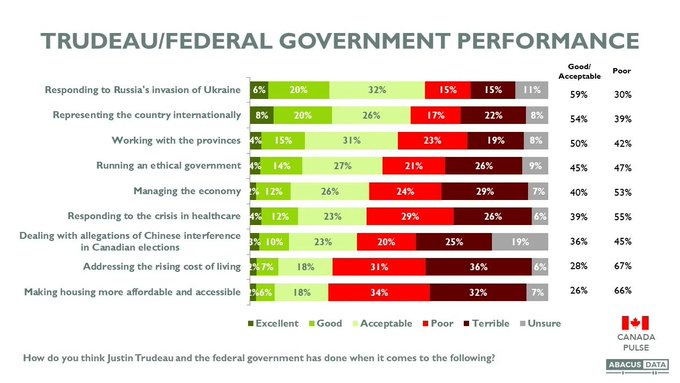

Right now, housing prices in Ontario have tripled over the last 10 years (from $330,000 to $920,000), and 66% of voters rate our performance on housing as “poor” or “terrible.”

The debate in meme form. I would simply push both buttons.

For anyone who’s going to be at the upcoming Liberal convention in Ottawa, if you’re concerned about housing, I’d love to meet up. John Grant of Urban Halifax is hosting a housing-focused hospitality suite. Please email me at russilwvong@gmail.com if you’d like to meet up with other housing-minded Liberals and talk about what you think we need to do on housing.

I like Reg Whitaker’s description of the Liberal Party as a combination of pragmatism and idealism. We want to win elections (if we can’t, our goals are irrelevant). But we also have idealistic goals - if not, what’s the point of winning elections?

First, let me try to summarize the “affordable housing only” view, which I disagree with.

Housing is a human right. We need to focus on those who are most vulnerable - those who are homeless. Prices and rents are being driven up by financialization. We can fund affordable housing by taxing new expensive market housing more heavily (progressive taxation, basically).

Pragmatically, also keep in mind that two-thirds of Canadians (and a larger proportion of Canadian voters) are homeowners, and that in Toronto and Vancouver, local opposition to new housing is very strong. Pushing hard for new housing can potentially split the Liberal coalition in Toronto and Vancouver between younger renters and older homeowners. (This is less of a concern for the Conservative Party, which doesn’t draw a lot of its support from Toronto and Vancouver.)

On the other side:

Even long-time homeowners are worried about where their kids can afford to live. People may not want new housing next to them, but they want more housing across the region. So new housing is unpopular at the local level, but popular at the provincial and national level.

Pragmatically, to win elections, you can’t just help people at the bottom - you need to help the middle class. Housing being so scarce and expensive in Toronto and Vancouver is a huge problem for middle-class voters. Younger people in Ontario are boiling mad.

We need a lot more housing. This really exploded during Covid (more remote work = more demand for space). The principle behind the carbon tax is, if you levy a heavier tax on something, you're going to get less of it. Same with housing.

We should totally build non-market housing (which was the focus of the 2017 National Housing Strategy), but we should support market housing as well. For example, when you add more people in a neighbourhood, more infrastructure may be needed, and the federal government can help by providing funding. (This is a big part of the Housing Accelerator Fund.)

Matthew Yglesias explains how even people who oppose housing right next to them are much more likely to support it across a wider area.

The real issue is that the upsides to housing growth accrue across a city, a metro area, or even a state, while the nuisances of new construction (parking scarcity, traffic, aesthetic change) are incredibly local. So if you ask a very small area “do you want more housing or less?” a lot of people will say that they think the local harms exceed the local benefits, and the division will basically come down to aesthetic preference for more or less density. But if you ask a large area “do you want more housing or less?” the very same people with all the same values and ideas may come up with a different answer because they [get] a much larger share of the benefits.

If we do decide as a party that we’re going to push for more housing, Mike Moffatt has some concrete suggestions:

I’ll also note that Trudeau launched the Housing Accelerator Fund recently, explicitly saying that its goal is to accelerate housing supply. Details.

More:

For a quick introduction to the housing issue, see Matthew Yglesias, The Rent Is Too Damn High (2012) - it’s a short book (68 pages). For a longer and more rigorous book, see Alain Bertaud, Order Without Design.

What the federal government is already doing: a mock debate, with AI-generated contributions by Pierre Poilievre and Jagmeet Singh.

How much housing do we need, and how long will it take to see results? CMHC estimates that to return to 2003-2004 levels of affordability, Ontario and BC need to build at more than 2X the business-as-usual rate for the next 10 years. Auckland upzoned in 2016; there was a huge increase in homebuilding, and after six years, rental affordability has already improved.

Montreal does a much better job than Toronto of keeping housing abundant and affordable. In Montreal, the selling price per square foot closely tracks construction costs, and it’s obvious how to make housing more affordable: lower costs.

Housing is a ladder: it’s all connected. When market housing is scarce, people move down the ladder. The result is trickle-down evictions and tremendous pressure on people near the bottom of the ladder.

Housing bottlenecks: Economic viability, rezoning, permitting, and construction. Construction should always be the bottleneck.

The importance of location: People want to live close to jobs. In a geographically central location, you’ll have more people wanting to live there, and land prices will be high. The natural response is to build taller buildings as you get closer to the centre, so that each household is consuming a relatively small amount of expensive land. When tall buildings aren’t allowed, it’s like pushing down on a balloon: people have to move further out.