Solving the housing crisis: Canada’s housing plan.

On Friday, Trudeau released a housing plan which includes a number of previously announced measures, plus some new ones, as a prelude to tomorrow’s federal budget. Summary of the new measures:

accelerated depreciation for new rental apartments (increasing CCA from 4% to 10%)

leasing public lands for housing

increasing Canada Mortgage Bonds limit from $40B to $60B (expanding MLI Select funding, for example)

another $1B for social housing via the Affordable Housing Fund, now $14B

$1.5B for new co-ops

$100M in funding for homes above existing retail, from the Apartment Construction Loan Program (formerly RCFI)

updating the National Building Code, e.g. to support point access blocks and single egress

loans for homeowners to add secondary suites

income verification to fight mortgage fraud

The overall plan is to produce nearly four million homes over 10 years, which is roughly doubling the business-as-usual rate of about 200,000 homes per year. It’s taking an “all-of-the-above” approach, similar to BC’s. Do we want to build more market housing, or more non-market housing? The answer is yes.

Twitter thread by Mike Moffatt.

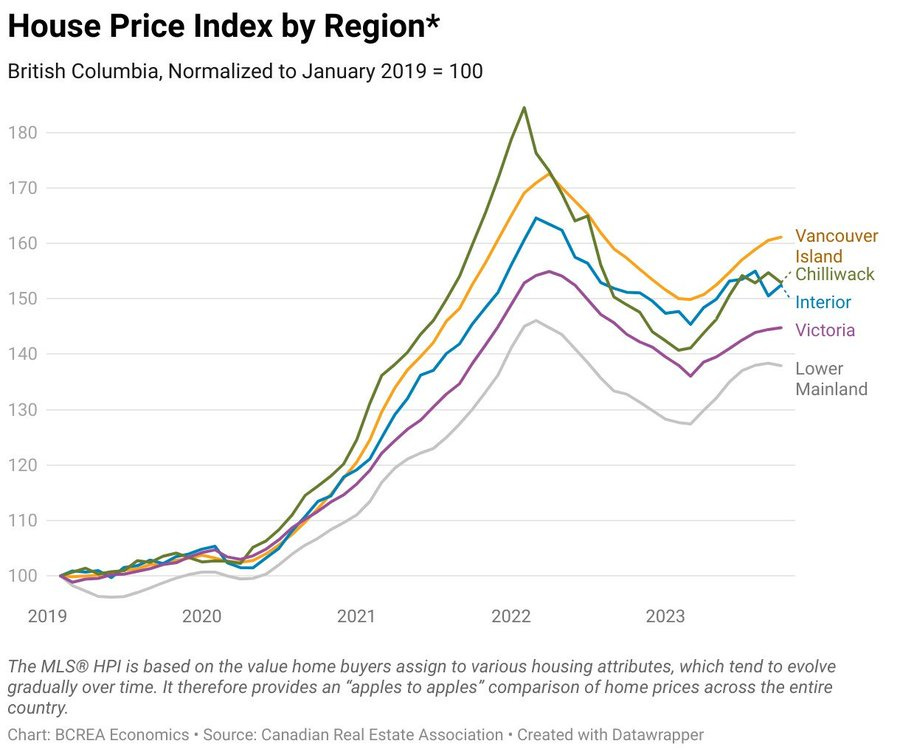

Demand shocks and the need for more supply

Since Covid, there’s been two major demand shocks.

There was a surge in people working from home, needing more space, and able to work from almost anywhere. The result is that the housing shortage is no longer a problem confined to Metro Vancouver and the GTA: it’s spilled over to the rest of the country. It’s now a national problem.

On top of that, there was a post-Covid boom in international students, especially at Ontario colleges.

In the short term, the plan is to cut population growth sharply. In January, Marc Miller imposed province-wide caps on international students, effective immediately, which cut Ontario’s numbers by about 50%. And then last month he announced that total population growth will be cut from 1.2 million in 2023 (!!) to 300,000, setting targets for temporary residents (minus 150,000 per year), not just permanent residents.

But in the medium term, we need to build more housing everywhere. The remote-work demand shock isn’t going to reverse itself. There’s a mismatch between where people want to live and work, and where our current housing stock is located.

People move where the jobs are. With remote work, there’s a lot of high-paying jobs which are no longer tethered to expensive housing in Toronto and Vancouver. Moving from Vancouver and Toronto to smaller centres has been great for the people moving, because their housing costs are far lower, but it’s caused tremendous pressure and displacement for locals. Home prices have risen even faster in small centres than in Vancouver and Toronto.

When there isn’t enough housing for the people who want to live somewhere - whether it’s people who grew up there and want to stay, or people moving there in search of cheaper housing - then prices and rents have to rise to unbearable levels to force people to leave.

To fix this, we need to build more housing. As Steve Lafleur says, we need to basically double the homebuilding rate everywhere, not just in the largest cities. And a lot of this housing will need to be denser - duplexes and four-plexes instead of detached houses, apartments instead of townhouses, high-rises instead of low-rises. Where home prices have risen a lot, land prices are high. Allowing more height and density means that each square foot of floor space doesn’t require as much expensive land.

Of course, these rules for what’s legal to build where (zoning restrictions) are set by municipal governments. And municipal governments decide what development charges must be paid by new housing (in Ontario and in BC they’re very high), which also serves as a barrier to new housing.

So what can the federal and provincial governments do about it?

Putting more money on the table

Municipalities are created by provincial legislation. So provincial governments can override municipal decisions, or even dissolve elected municipal bodies and appoint replacements - the BC government has done this more than once to the Vancouver School Board.

In BC, David Eby and the BC NDP have been making full use of this power, requiring municipal governments to make multiplexes and transit-oriented development legal, and requiring them to set fixed development charges instead of negotiating them on a project-by-project basis. In contrast, in Ontario, Doug Ford and the Conservatives have had recommendations from a task force sitting on their desks for the last two years, including that the province allow four units and four storeys everywhere. Ford recently announced that the Ontario government will not be going ahead with this.

Unlike the provinces, the federal government doesn’t have the power to directly override municipal decisions. But Sean Fraser has demonstrated that that it’s possible to use federal funding, in the form of one-time payments from the federal Housing Accelerator Fund, to convince municipal governments to do the right thing. The agreements are similar to what BC is doing: make four-plexes legal by right, allow more height and density near frequent transit and near universities.

More recently, Trudeau announced that the upcoming budget will include a new $6B Canada Housing Infrastructure Fund, with $1B for municipalities and $5B for the provinces. The conditions for provinces to receive funding are very similar to those recommended by the cross-partisan Blueprint for More and Better Housing. They’re also similar to what the BC government is doing:

Require municipalities to broadly adopt four units as-of-right and allow more “missing middle” homes, including duplexes, triplexes, townhouses, and other multi-unit apartments.

Implement a three-year freeze on increasing development charges from April 2, 2024, levels for municipalities with a population greater than 300,000.

Adopt forthcoming changes to the National Building Code to support more accessible, affordable, and climate-friendly housing options.

Require as-of-right construction for the government’s upcoming Housing Design Catalogue.

Implement measures from the Home Buyers’ Bill of Rights and Renters’ Bill of Rights.

And there’ll be a new public transit fund for municipalities, with conditions:

Eliminate all mandatory minimum parking requirements within 800 metres of a high-frequency transit line.

Allow high-density housing within 800 metres of a high-frequency transit line.

Allow high-density housing within 800 metres of post-secondary institutions.

Complete a Housing Needs Assessment for all communities with a population greater than 30,000.

Tax incentives for purpose-built rentals

An illustration of the cost bottleneck. Cost increases are first absorbed by “land lift” (shown in green), but once that’s gone, they end up being paid by homebuyers and renters. It doesn’t just affect prices for new buildings, it also affects prices for existing buildings, since they compete with each other.

Because the economy has been running hot, both workers and materials are in short supply, raising costs. The Bank of Canada has raised interest rates sharply to bring down inflation, increasing the cost of borrowing money for construction. The result is that a lot of projects are no longer economically viable.

Recommendation 03 from the National Housing Accord identifies a number of measures to improve economic viability

Remove GST/HST from new capital investments in purpose-built rental housing.

Defer capital gains tax and recaptured depreciation due upon the sale of an existing purpose-built rental housing project, providing that the proceeds are reinvested in the development of new purpose-built rental housing.

Increase the Capital Cost Allowance (CCA) on newly constructed purpose-built rental buildings.

The CMHC should examine the point system in the MLI Select program for new construction to increase the number of purpose-built rentals that are affordable.

In September, Trudeau, Chrystia Freeland, and Sean Fraser announced that the federal government will remove GST from new rental housing. A project that builds new rental housing will no longer need to cut a large cheque for GST.

A second big change is accelerated depreciation for new rental housing. Why this is a big deal: it offsets taxable income, and therefore reduces the tax that the owner of the building has to pay. Like waiving the GST on new rental housing, it makes rental projects more attractive.

How are these changes going to help? Short answer: They’ll get hundreds of thousands more rentals built. People living in them won’t be competing with everyone else and driving up rents, so this will help to put downward pressure on rents.

In both cases, the federal government is putting more money on the table, because this means sacrificing tax revenue.

Low-cost, long-term loans for purpose-built rental housing

We need a lot more purpose-built rental housing, even if it's at market rents or close to it. The Apartment Construction Loan Program provides low-cost, long-term loans for rental housing. There’s often stories talking about rentals built with funding from the ACLP not being affordable, because they’re close to market rents - a recent example - but that’s exactly what the ACLP is for. (There's a separate Affordable Housing Fund aimed at affordable housing.)

Recommendation 04 from the National Housing Accord:

Despite Canada’s affordability crisis and housing shortages, housing starts are falling due to rapidly rising interest rates. Existing financing mechanisms have been criticized for having unclear underwriting criteria, lengthy approval times and inconsistent market rate evaluation methods. In a period of rising and volatile interest rates, developers face significant risks when building new affordable purpose-built rentals or upgrading existing units for energy efficiency and their interest payments will rise in the future.

These problems can be solved if the CMHC or the Canada Infrastructure Bank were to provide 25-year, fixed-rate financing for projects, including both new builds and upgrades, that meet certain accessibility, affordability, and climate-friendly criteria. The CMHC should also be provided with additional funding to increase the underwriting resources to expedite approvals or to outsource the approval process based on defined criteria, as currently, developers often have to obtain interim financing while waiting for approval on a CMHC loan.

In Vancouver, renting is far less expensive than owning, even at market rents. Vacancy rates in Metro Vancouver have been close to zero for years, and with the Covid spillover of housing demand from Vancouver and Toronto, vacancies are low across the country.

Purpose-built rental housing, owned by a pension fund or REIT, provides much more security compared to renting a condo or basement suite from an individual landlord who can reclaim the space for personal use. But in Vancouver, there was something like 40 years where we basically built condos and no purpose-built rental housing. Most of the rental housing stock was built back in the 1960s and 1970s.

The primary purpose of the Apartment Construction Loan Program (previously the Rental Construction Financing Initiative or RCFI) is to provide low-cost long-term loans for new purpose-built rental housing. Senakw is probably the highest-profile project with RCFI/ACLP funding, but there's lots of smaller ones.

According to Steve Pomeroy, the Liberal promise in 2015 to remove the GST on new rental housing ran into a lot of opposition from senior civil servants in the Finance department. They proposed the RCFI as an alternative. The affordability criteria were added by cabinet, but they're relatively weak.

Comments on the overall plan by Mike Moffatt

Thread time. Not surprisingly, reviews are mixed about yesterday's federal housing plan. My question for both the supporters and skeptics is: "What would you like to see a government do... any government... to address the housing crisis?"

The one I hear a lot is, "cut population growth". The federal government did that. Our population growth levels, which exceeded 1.2M, are going all the way down to 300K a year, a 75% reduction. This was confirmed this week by the Bank of Canada.

Next thing I hear is "cut taxes on housing construction". To which I say: YESSSSSSSSSS! Taxes, fees, development charges, etc. are approximately 31% of the cost of building a new home.

The feds have:

Eliminated the GST on apartment construction

Re-introduced the 10% ACCA on apartment construction

Prohibited cities with more than 300K persons from raising development charges

Meanwhile, Ontario is giving municipalities more powers to raise dev charges.

Development charges are a massive problem! They've gone up over 800% in the last two decades. And yet the province is allowing municipalities to hike them further!

I wish the feds had gone much farther in blocking this, but it's a start.

Another thing governments can do: Open up more land for development, lowering the cost of land. (Which is also up about 800% in 20 years in cities like London.)

Feds have opened up a lot of federal land for development (which the Tories have also called for. It's a good idea)

On the social housing side, there's also a lot here. Though it's totally reasonable to point out that it isn't enough to undo the 30+ year lack of investment in this space.

That's not to suggest it's a perfect plan or includes everything. I would have liked to see more here about making sure new home construction is low-carbon and resilient to extreme weather events. We have some ideas on how to do so here.

And I think they need to do more on the tax side. The proposed reforms to the tax treatment of REITs, plus the upcoming EIFEL changes are having a large, chilling effect on investment. Feds need to reverse these, as Cara Stern and I discuss here.

Finally, it's totally fair to suggest that these measures should have been taken years ago. Also totally fair to be skeptical about implementation.

But that aside: What would you like to see governments (fed, provs, or munis) do to address the housing crisis?

Comparison to Poilievre’s housing plan

From September 2023: Poilievre releases housing plan he says would 'build homes, not bureaucracy'.

Tie federal funding to municipalities to the number of housing starts

Offer "big bonuses" to municipalities that surpass a target of 15 per cent more homes built every year. Claw back money from municipalities that fall short of that target.

Implement a "NIMBY" fine on municipalities that block construction because of "egregious" opposition from local residents.

Demand that the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) accelerate approval of financing for projects and threaten to withhold bonuses from CMHC staff if they fail to do so.

Eliminate the GST on affordable apartment housing to spur development.

Sell off 15 per cent of federally owned buildings so the land can be used to build affordable homes.

Poilievre's plan puts a lot less money on the table. The municipal bonuses would come from a $100M fund; Sean Fraser's been using a $4B fund to convince municipalities to legalize more housing. The GST cut is much more limited: it only applies to below-market rentals).

Now that the Liberals have released their plan, it’s possible that the Conservatives will update their plan to put more money on the table.

More

National Housing Accord, August 2023.

Blueprint for More and Better Housing, March 2024.

The Great Rebuild: Seven ways to fix Canada’s housing shortage. Robert Hogue, RBC, April 2024.