We need excess capacity

If people are building right up to the limits, restrictions are too tight

A rule of thumb: if people are building right up to the regulatory limit, that indicates that the limits are too tight (“binding”). The regulations are preventing people from building more housing, resulting in a shortage of housing.

Some examples:

Large gap between cost per square foot and price in Vancouver and Toronto

A 2018 analysis by CMHC found a large gap between the cost of adding one more floor to an apartment project in Metro Vancouver or the GTA, and its selling price. This gap exists because municipal governments prevent projects from adding more height and density.

Results of this analysis suggest that the marginal cost of producing new apartment units is far below the average price per square metre that they sell for in Vancouver and Toronto, whereas this is not the case for Montreal.

In a well-functioning market, prices shouldn’t be much higher than costs. When they are, something’s very wrong.

The methodology of this report follows closely the methods deployed by Glaeser, Gyourko and Saks (2005). In a well-functioning market without market power, they argue, the price of a housing unit will be equivalent to its average cost of production. In the long run, the average cost of production is equal to the marginal cost of production. A difference between price and cost will erode as new builders enter the market to provide new supply and compete on price. Competition will continue to add supply and push down prices until prices are equal to marginal costs.

Vancouver’s floor space restrictions

This graph, by Jens von Bergmann and Nathan Lauster, shows the ratio of floor space to lot size (floor space ratio or FSR) for all single-family houses in the city of Vancouver, based on when they were built. Initially, the floor space would vary depending on the lot size. As land prices rose:

By the mid 1970s the range of FSR narrowed considerably, approaching the legal limit. What changed is that the land economics incentivized people to maximize floor space. The FSR constraints, and with it land sharing constraints, became binding and the zoning became dysfunctional.

More recently the FSR limit was increased to 0.75, which is clearly visible in the data. It’s now been decreased again.

1000 Cypress St. vs. Senakw

An old two-storey, eight-unit rental building, built in 1972, in Kits Point. Under the city’s zoning, it can’t be replaced with a new building of the same size, so it’s getting replaced with three single-detached houses.

Five minutes down the street, on a small parcel of Squamish reserve land, where the city’s restrictive zoning doesn’t apply, the Senakw project is building high-rises up to 60 storeys tall:

Spot rezoning vs. broad upzoning

Note that there’s a big difference between removing zoning restrictions in just one spot, and lifting them everywhere. When there’s a massive shortage of housing, and there’s very few parcels of land where new housing can be added, those parcels will be extremely valuable. The result is that they’ll be built for very high density.

What’s driving up the price of lots where you can redevelop is that there’s so few of them, because you can’t add housing to most lots.

With broad upzoning, where you’d be able to build small apartment buildings by right on most lots across the city, the price of any individual lot would no longer be bid up by artificial scarcity. Shane Phillips, Building Up the "Zoning Buffer": Using Broad Upzones to Increase Housing Capacity Without Increasing Land Values, 2022.

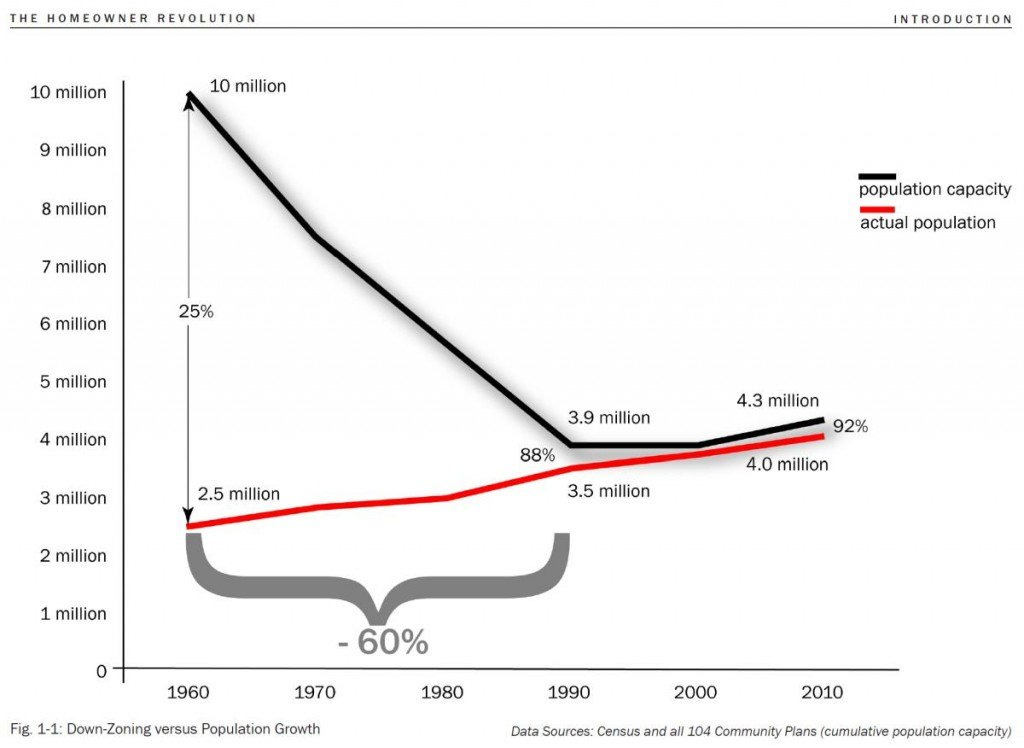

Imagine, for the sake of argument, that every parcel in Los Angeles currently zoned for single-unit detached homes, duplexes, and triplexes was rezoned to allow up to 10 units in modest three- and four-story buildings. With more than 400,000 such parcels in Los Angeles, this would increase the city’s zoning capacity by at least 3.6 million units, 2 ½ times the city’s existing stock of 1.4 million homes and more than its estimated capacity in 1960. There are approximately 25,000 single-family homes sold on these parcels each year; if just 5,000 of these were sold and redeveloped to their maximum capacity, the city would add 45,000 units to its housing stock annually.

Recalling our hypothetical town and the scenario in which 50% of parcels are rezoned to allow for triplexes, homeowners in this 10-unit scenario cannot sell their parcels for a premium — there are too many just like them. The capacity for housing has increased, but the land price has not. Value capture is not necessary (nor is it feasible) because lower land prices will automatically be “captured” by renters and homebuyers in the form of lower rents and sale prices.

More

In BC, Bill 44 requires municipalities to have Official Community Plans that will meet their housing forecasts for the next 20 years or more.

Jonathan Nolan of YIMBY Melbourne suggests that it’d be better to measure the distortions caused by zoning, as opposed to excess capacity. How to measure the impact of zoning on housing in your city, May 2024. It’s eye-opening to read because he describes these distortions as bad (they’re a measure of how zoning is blocking housing where people want to live), but our current institutions call it “land lift” and regard it as good (because most of it can be extracted by municipal governments to keep property taxes low).

Joseph Politano, Capitalism and the Surplus Economy, October 2021. Describes Janos Kornai’s comparison between centrally-planned economies, where managers hoard materials and workers, resulting in shortages, and market-based economies, which rely on surplus capacity to the point of wastefulness. The future is uncertain. If we can’t exactly calibrate how much we’re going to need, having surplus capacity is far better than suffering from chronic shortages.