Against defeatism

Homeowners are more worried about neighbourhood change than property values

Politicians are just people. We elect them to deal with large-scale challenges, like housing being scarce and therefore expensive. And we expect them to come up with solutions.

But do they themselves believe that there are solutions? Or are they just engaging in the kind of evasive “issues management” that Brian Kelcey describes in this Twitter thread?

Matthew Yglesias describes how in the US, people used to be defeatists on housing, believing it was impossible to overcome opposition from incumbent homeowners. Ten years of YIMBYism have accomplished a lot, October 2022:

People newer to the discourse probably don’t realize the extent to which this cause was considered hopeless just 10-15 years ago.

The people from whom I first learned the substance of the land use issue were basically defeatists. Their view was that exclusionary zoning was bad, and that it contributed to an affordability crisis and to segregation, but that it also had a deep and fundamental logic to it. Homeowners benefit from scarcity and strong local veto, homeowners care a lot about land use issues, and elected officials are highly responsive to homeowners — they saw exclusionary zoning as an essentially unavoidable fact about the world.

Do politicians in Canada hold this view? Because if they don’t think the problem can be fixed, they’re not going to fix it.

Homeowner opposition to new housing

I’d say that there’s two distinct reasons for homeowners to oppose new housing:

Fear of the unknown. In Vancouver and Toronto, because zoning is so restrictive, almost every multifamily project has to go through what amounts to a mini-referendum. People like their neighbourhood the way it is; if you ask them if they want it to change, it’s natural for them to say no.

Not wanting the value of their property to go down.

I actually think that fear of the unknown is more important than concern over property values. Opposition tends to be hyper-local. Building a lot more housing would affect property values city-wide, but it’s only the people who are right next door who are strongly motivated to oppose it.

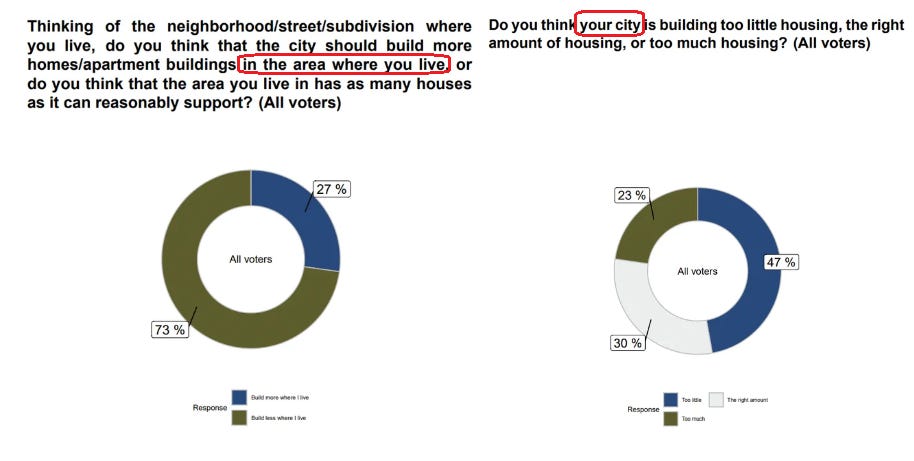

Evidence from a Toronto poll by Mainstreet, May 2023 (shown above): 73% were opposed to more housing in their neighbourhood. But only 23% were opposed to more housing across the city, which is what would affect property values.

As Matthew Yglesias explains:

The real issue is that the upsides to housing growth accrue across a city, a metro area, or even a state, while the nuisances of new construction (parking scarcity, traffic, aesthetic change) are incredibly local. So if you ask a very small area “do you want more housing or less?” a lot of people will say that they think the local harms exceed the local benefits, and the division will basically come down to aesthetic preference for more or less density. But if you ask a large area “do you want more housing or less?” the very same people with all the same values and ideas may come up with a different answer because they internalize a much larger share of the benefits.

Another poll, May 2023: Toronto residents want to see more housing built, even if it means fewer parking spots and detached homes. “When asked which was more important, more housing or preserving the character of Toronto neighbourhoods, voters chose housing by a margin of 40 percentage points,” Liaison Strategies Principal David Valentin said in a statement. 58% chose housing, 18% chose neighbourhood character. Twitter thread by Alex Beheshti.

In Vancouver, the evidence seems even stronger, with less opposition to neighbourhood change.

In the October 2022 municipal election, sitting city councillor Colleen Hardwick ran for mayor, appealing to people who fear and oppose new housing. Her campaign was run by Bill Tieleman, a skilled political operator and NDP veteran. She only got 10% of the vote.

A Research Co poll (Mario Canseco) conducted in April 2019: “71% of Vancouverites think the city should allow the construction of duplexes, fourplexes, townhouses, and 3-4 storey apartments in neighbourhoods where now only single-family homes are permitted.”

In May 2019, Burnaby ran a one-day workshop with about 100 people who were primarily selected at random, rather than self-selected. It was also a deliberative process, with an initial briefing to provide an overview of the key issues and options, and with discussion in small groups. The results were similar. “The City of Burnaby should allow four- to six-storey apartment buildings in single-family residential neighbourhoods. That’s what 70 per cent of respondents told the city’s housing task force at a recent workshop (44 per cent strongly agreed, while 26 per cent agreed with the idea).”

Dealing with hyperlocal opposition

A pessimistic take: maybe the hyperlocal-opposition dynamic is exactly like trying to cut spending to balance the budget? Everyone’s in favour in principle, but when it comes time to make cuts to any specific program, it turns out that a majority of voters are opposed.

But the answer is no. A strong majority of voters want more housing, and in addition, for any specific project, a majority of voters want to see it built.

So why is it so hard to get housing approved? It’s a self-selection problem. When you hold a public hearing on a project, you don’t get a random sample of voters who show up and speak - you get a hyperlocal sample of people who are most worried about change to their neighbourhood. (And someone who’s particularly anxious and fearful will be highly motivated to show up. Frances Bula reports that during a rezoning for additional housing above a new school in Coal Harbour in Vancouver, one opponent said they were worried about kids falling into the water.)

To counterbalance this opposition, there’s a number of pro-housing groups that have formed in recent years. In Toronto, More Neighbours Toronto; in Vancouver, Abundant Housing Vancouver; in Victoria, Homes for Living.

We mobilize support for projects which draw a lot of opposition. A recent example in Vancouver, rezoning for non-market housing in False Creek North: there were 27 comments opposed (citing concerns like views), three in favour. We put the word out on Reddit. In 24 hours, people submitted 800 comments in favour. When you ask the broader community, it turns out that people do indeed support more housing.

Enjoyable though this kind of battle is, it’s not a great use of council and staff time. One of the key recommendations of the MacPhail Report was that municipal governments should focus on city-wide policy, rather than making a decision on each and every individual project on a site-by-site basis.

Another approach is to set land-use policy at a higher level, as has been happening in California and other US states. This is exactly what BC is doing. Why provincial action makes sense.

Why would homeowners not be concerned about more housing affecting their property values?

The most obvious reason: most people in Vancouver and Toronto believe that property values always go up in the long run. So why would they worry about something that they don’t think will happen?

A second reason: Glaeser and Gyourko point out that for someone who’s not planning to move (which describes most homeowners in Vancouver), it doesn’t matter that much if the price goes up or down.

Housing wealth is different from other forms of wealth because rising prices both increase the financial value of an asset and the cost of living. An infinitely lived homeowner who has no intention of moving and is not credit-constrained would be no better off if her home doubled in value and no worse off if her home value declined. The asset value increase exactly offsets the rising cost of living (Sinai and Souleles 2005). This logic explains why home-rich New Yorkers or Parisians may not feel privileged: if they want to continue living in their homes, sky-high housing values do them little good.

A third reason, probably less salient to most homeowners, is that allowing more density is win-win, as explained by Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy in 2016 and demonstrated by the empirical data from Auckland’s 2016 upzoning. The price of higher-density housing (apartments) went down, because there were more of them. The price of lower-density housing (single-detached houses) went up, because the land could be redeveloped for higher-density housing.