Complex-care housing

For the highest-need cases, who need intensive 24/7 support

There was a big announcement from the provincial government in January 2022: they're setting up "complex-care housing" for the highest-need cases of street homelessness, people needing intensive 24/7 support due to drug addiction, mental illness, or brain injury.

The provincial government announced today it is initiating complex-care housing, which provides residents with 24/7 wrap-around supports. This is also a step in the direction of the community care type of model that was intended to replace institutionalized care, following the closure of Riverview Hospital.

Unlike supportive housing, complex-care housing provides residents with treatment and specialized care, such as support from nurses, social workers, and other health professionals.

Specific clinical services and other supports include physical, mental health, and substance use care, and psychosocial rehabilitation, as well as proper food nutrition, social and community supports, and personal care and living supports.

In the initial phase, there's four facilities with about 100 spaces in total: two in East Van, one in Surrey, one in Abbotsford, expected to open later this year. Funding is about $50,000 per space, or $5M per year. The estimate is that province-wide, there's about 2000 people needing this level of support, which translates to about $100M per year in total.

The April 2022 budget allocated more funding, to provide 500 spaces by 2025.

One question is whether treatment would be voluntary or involuntary, and the answer is that it'll be voluntary. It sounds like they're already thinking about what happens if somebody's not cooperative enough to stay in complex-care housing.

Individuals who “escalate” within a complex-care housing setting will be sent to facilities such as the newly-opened, 105-bed Red Fish Healing Centre for Mental Health and Addiction at the former Riverview Hospital lands in Coquitlam, and the recently-built, 75-bed Mental Health and Substance Use Wellness Centre at Royal Columbian Hospital in New Westminster.

The minister at the time was Sheila Malcolmson:

“If somebody does escalate, if they go off medication or deepen into addiction or have PTSD manifest, the wrap-around supports can anticipate that. The care plan that is developed for the individual and partnership gets us ready to soften the fall or move to a higher level of care, and then have that housing secured and protected for them when they return from a higher level of care, whether that be primary care or mental health,” said Sheila Malcolmson, BC Minister of Mental Health and Addictions, during the press conference.

Malcolmson has emphasized that complex-care housing is completely voluntary. Nobody will be involuntarily detained under complex-care housing.

“If someone is a risk to themselves or others, there are tools in the Mental Health Act to detain them involuntarily. That is a tool that exists now with or without complex-care housing, and it has been identified that when people are admitted to hospitals, sometimes under the Mental Health Act, that can be a trigger for them to lose the housing they have already. And when they are discharged, they are in a worse situation than when they started,” she said.

“This is something we want to avoid, and that’s one of the central designs of complex care housing — retaining housing no matter where people need to seek treatment, they will have a safe place to return to.”

Over the past two years, the significant rise in unsheltered homelessness is partially attributed to individuals being evicted from supportive housing due to their untreated aggression, substance use, and often with acquired brain injury.

The current minister is Jennifer Whiteside, appointed in December 2022.

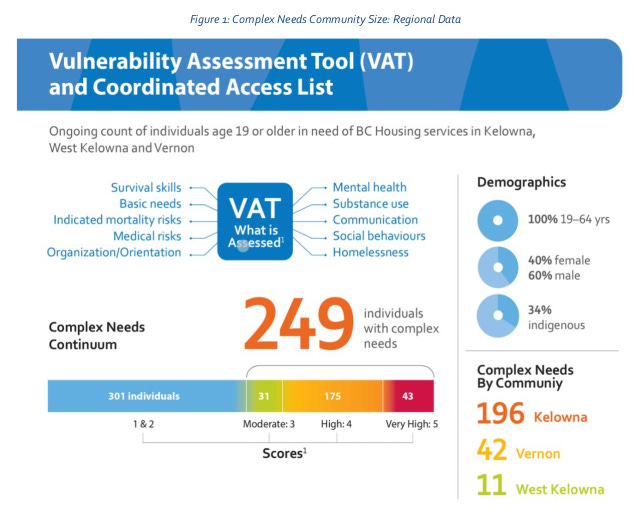

A detailed analysis from Kelowna

For a detailed look at how complex-care housing is intended to work, see the Complex Needs Advocacy Paper for Kelowna, July 2021. Prepared by a team of consultants led by Urban Matters CCC.

Includes a summary of research and needs assessments.

Extensive research has been conducted to further understand the prevalence and impacts of complex needs within the homeless population. A 2019 study including 1000 people experiencing homelessness across Toronto, Ottawa and Vancouver identified that “substance use is a significant barrier to exiting homelessness and further exacerbates social marginalization. Substance use among persons who are experiencing homelessness has also been associated with early mortality, chronic physical illness, and longer periods of homelessness. In addition, a substantial proportion of homeless individuals with substance use disorders also suffer from other mental disorders” (Palepu et al., 2019, p.2).

Social service providers in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver have reported a lack of appropriate healthcare supports and housing transitions for individuals with complex needs who need supported care throughout their lives due to their severe underlying mental health needs.

Between 2007 – 2013, the Vancouver Police Department (VPD) produced multiple reports to highlight the rising trend of violent episodes involving individuals with mental health challenges as well an observed increase in the use of emergency department and crisis services by the same population (VPD Report, 2013, p. 1).

The VPD put forth a range of recommendations for a combination of crisis support, healthcare and housing support teams to address the challenges with housing individuals with complex needs. The Province carried out a review in 2013 in response to the VPD report and supported some of the recommendations to establish additional mental health and/or addiction support services.

However, there is yet to be a response to establish a coordinating authority or program that seeks to coordinate the delivery of housing, health and social support services to meet the medical and housing needs for individuals with complex needs. The current system of dispersed services streams for mental health, substance use and housing, although successful for certain subsets of the homeless population, has demonstrated to be unsuccessful in addressing the needs of individuals with complex needs.

Takeaways from a survey of service providers:

An estimated 50-75% of clients accessing social services experience complex needs. Many organizations operate at capacity, which indicates there may be additional people with complex needs who are not accessing services.

There is no housing that is designed specifically for people with complex needs. There is a need for more integrating of health supports into housing with supports that are tailored for adults with complex needs. The location and design of housing for people with complex needs is critical; individuals typically need quiet and calm spaces that help to limit negative interactions with other clients or neighbours. Ellis Place which opened in Kelowna in November 2020 aims to provide greater supports for this population.

There is a service gap for youth with complex needs for several different reasons (e.g. youth aging out of care, lack of supportive housing options).

There is a lack of qualified staff with specific training to support individuals with complex needs. Client to staff ratios for people with complex needs are high, such that those who are qualified often don’t have the resources or bandwidth to adequately support these individuals. People with complex needs require a high level of attention from staff, which makes it difficult for social serving organizations (and housing sites, in particular) to allow them to stay when organizational capacity is low.

Current supportive housing is typically a larger building with 40-50 apartments. The paper suggests a range of smaller-scale housing types:

Current staffing model for supportive housing, versus what’s needed:

The fit and form of the infrastructure has most typically been larger scale 40-50 unit facilities, presumably working toward economies of scale with scarce public funds. The operator contracts typically cover two support workers who are responsible for supporting the approximately 50 individuals living on-site. Staff will typically receive training in de-escalation, overdose awareness, cultural awareness and harm reduction.

The wage for these positions is in the range of $19.50-$24.50 per hour, and these positions are often filled by individuals with high school degree or perhaps a human services diploma; and the career trajectory and related compensation is such that it discourages those with deeper qualifications and skills from making a career choice in this area. Individuals who have qualifications don't stay in these positions for long and will move on to higher paying clinical positions that usually have more standard hours. Local service providers observe compounding factors of high stress and burnout as contributing to high rates of staff turnover in supportive housing units and shelters (and the sector in general).

A new supportive housing building on Ellis Street in Kelowna opened in November of 2020 and is testing a new model that aims to help support individuals with higher complex needs to maintain stable housing -approximately 28-30 tenants in the building have complex needs. The building is smaller scale than what has been typical – with 38 units on site. An Interior Health supported clinical team is operating 7 days a week for 8 hours per day. The team includes a psychiatric nurse practitioner and a social worker who work with the housing and support team. This team has enabled building tenants to receive much more streamlined and faster health supports than would be possible through accessing community health supports only, resulting in tenants receiving stabilizing health supports much more quickly.

Annual cost for a staff team to support about 20 people would be roughly $600,000 (probably higher in Metro Vancouver). As the paper notes, a preventive approach is likely to be more cost-effective than a crisis-driven approach.

More:

City of Kelowna page on complex needs.

BC government page on complex-care housing. Includes a draft strategic framework, but it’s less detailed than the Kelowna advocacy paper.

Minister says B.C. working at a ‘sustainable’ pace to implement complex care housing plan. Mayors say that’s not enough. Frances Bula in the Globe and Mail, August 2022.

BC Budget 2023 - includes funding for complex-care housing.

Homelessness is a housing problem, by Aaron Carr, not primarily a problem of drug addiction or mental illness. The Economist makes similar points, observing that in the US, only 35% of homeless people have no shelter, and only about a third of those people are chronically homeless.

Comments on Reddit from a formerly homeless person, identifying security as a key problem. “When I was homeless, the biggest threat to me was other homeless people, both men and women. I didn't stay in shelters because people would randomly assault and steal from you and no one would do anything because endless second, third, fourth chances are given, but as a victim, you don't get more chances, you just have to learn to avoid the places the people who harass you are.”

Last week the city of Vancouver dismantled the Hastings Street homeless camp, which had been there since July 2022. City of Vancouver vows to find alternative to DTES 'street sweeps', Vancouver Sun, June 2022. Two arrested for assault as dozens of tents and structures removed from East Hastings Street, Vancouver Sun, April 2023.