Cape Breton University and the international student cap

Deny Sullivan on the impact in Nova Scotia

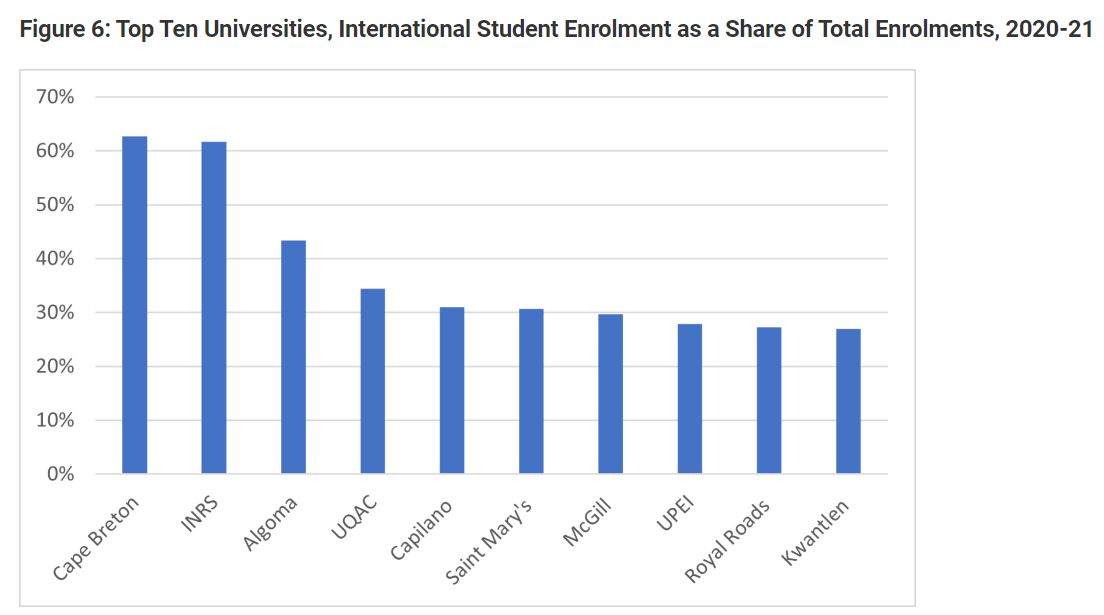

It’s not just Ontario colleges that have been bringing in amazing numbers of international students. Cape Breton University in Sydney, Nova Scotia is often mentioned. CTV News, April 2023: Priest, neighbours issue plea for help for struggling international students in Cape Breton.

Deny Sullivan, What the international student cap means for Nova Scotia:

A lot of attention has gone to the stress GTA-area colleges have put on Toronto rental markets. But I think it’s likely that no housing market will feel this international student cap quite like Sydney, Nova Scotia.

CBU will have to cut enrolment by about 4,500. The population of Sydney in the 2021 census was 30,970. Cape Breton as a whole has about 93,000 residents. The enrolment reduction could reduce Sydney’s population by a stunning 15% (or the entire regional population by 5%). CMHC reported a 0.8% vacancy rate in Cape Breton as of October 2023 - that is sure to rise next year if my numbers are anywhere close to reality.

More

The federal cap on international students continues to reverberate.

Mike Moffatt in the Globe: Canada is failing the grade on housing. Fixing that starts with international students, but it shouldn’t end there. A long op-ed, explaining both the surge in international student numbers (Ontario and Ontario colleges were being greedy, exploiting international students like "shaking a money tree"), as well as the need to build more housing and specific recommendations for doing so.

There is no shortage of ideas for them to consider. Intelligent public policy could help convert underused office space into housing, particularly dormitory-style housing for students. Government-mandated parking minimums raise the cost of housing construction and restrict the available land to build on; these rules could be abolished. Existing building-code rules make building family-sized apartment units in our cities cost-prohibitive, and Canada could take a lesson from Sweden, which legalized single-exit designs for apartments of up to 16 storeys, allowing for the construction of a more comprehensive array of floor plans with larger units.

Beyond individual policies, though, what Canada needs most are co-ordination and alignment between our housing and population growth policies, as well as robust population forecasts to plan our needs not just in housing, but in schools, hospitals and other public infrastructure, too. Capping yearly non-permanent resident growth, in the same way that the country caps immigration, is essential for this planning. Canada may have been caught off-guard by how quickly our population has grown in the past two years, but this failure to forecast cannot happen again, as it doesn’t just affect our housing market – it puts Canada’s entire immigration system in disrepute with Canadians.

The good news is that we have a chance to do it all: simultaneously solve Canada’s housing crisis, grow our population, address the climate challenge and have a flourishing high-education system. We can build enough housing for existing residents and the newcomers who contribute so much to Canada’s economic and cultural vibrancy. And the vision to attract the best and brightest to the country to offset the effects of an aging population is sound, too: Integrating the higher-education system into the immigration system to give newcomers Canadian credentials and experiences is fantastic and should not be abandoned. But to achieve this, we need public policies that meet the ambition of our vision to ensure that everyone in Canada, regardless of how long they have been here, has a safe and secure place to call home. A reactionary cap from one level of government, while necessary, cannot be the limit.

Bloomberg: Canada Must End Reliance on Cheap Foreign Labor, Minister Says.

Canada’s immigration minister is taking steps to curb the country’s dependence on temporary foreign labor and international students, prompting pushback from business groups that say there aren’t enough domestic workers available to sustain parts of the economy.

Marc Miller introduced a limit on foreign student visas last month, cutting them by 35% for this year. He will announce further changes soon to restrict students’ off-campus work hours and he’s also reviewing the country’s temporary foreign worker program, he told Bloomberg News in an interview.

“We have gotten addicted to temporary foreign workers,” Miller said. “Any large industry trying to make ends meet will look at the ability to drive down wages. There is an incentive to drive labor costs down. It’s something that’ll require a larger discussion.”

Another interesting quote:

Many foreign students are not getting the experience they were promised by colleges that are exploiting them for profit, Miller said.

“The question we posed to ourselves is: do we want that short-term gain for a lot of long-term pain?” he said, adding that some colleges have been relying on “fast money” that harms young people and their families. “Institutions that have profiled models of growth that are no longer tenable will perhaps have to shut down if it’s done properly.”

Finally, an analogous situation with a similar solution: Matthew Yglesias observes that tourism has benefits as well as costs. (Both tourism and international study are exports.) You want to be pragmatic and manage it so as to maximize the benefits and minimize the costs. “Whatever the downside of being a place that everyone wants to go, it’s a lot worse to be a place that nobody wants to go.”

I’ve never been to Peru. But I did read a lot of articles 10-15 years ago about “overtourism” at Machu Picchu. The basic premise of the stories wasn’t crazy. Even though Machu Picchu is very old, it’s pretty new as a tourist attraction. An American explorer rediscovered it in 1911, it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983, and as recently as 1996 it was getting fewer than 400,000 visitors per year. Tourist traffic increased roughly four-fold over the next 20 years, though, and that generated a lot of stress on the site.

All these “overtourism” articles were driving me crazy, though, because clearly there was a lot of demand to visit Machu Picchu, so the government should ration access, charge visitors, and use the financial surplus to invest in preserving the location.

It turns out, per this 2018 Condé Nast piece by Tyler Moss, the Peruvian government also thought of this and it worked out just fine. They moved on from a crisis over the conservation of a priceless part of their cultural legacy to banal concerns about whether the bathrooms were too inconvenient.