Burnaby: "masters of the old paradigm"

Brendan Dawe explains: maximize revenue, ignore high prices

Alec Lazenby, Vancouver Sun:

Under Bill 47, which passed last fall, Metro Vancouver municipalities were required to pass bylaws [by June 30] to allow housing developments of up to eight to 20 storeys near SkyTrain stations and eight to 12 storeys near bus exchanges.

As first reported by Global News, Infrastructure Minister Rob Fleming wrote to Langley Township Mayor Eric Woodward in late July, after township council missed the June 30 deadline to recognize the site of the future Willowbrook SkyTrain station as a transit-oriented development zone.

At a council meeting on June 24, Burnaby council unanimously voted to put off the changes for three months in order to allow staff to further study the legislation and the impacts it will have on neighbourhoods like Brentwood, where residents have signed a petition seeking an exemption from the requirements.

Ravi Kahlon is now telling them that they have until October 31 to comply.

BC to municipalities: you can’t keep ignoring high prices

The MacPhail Report observed that incentives for municipalities are backwards. Because they take 70-80% of the increase in land value, they have a direct financial incentive to keep land prices high.

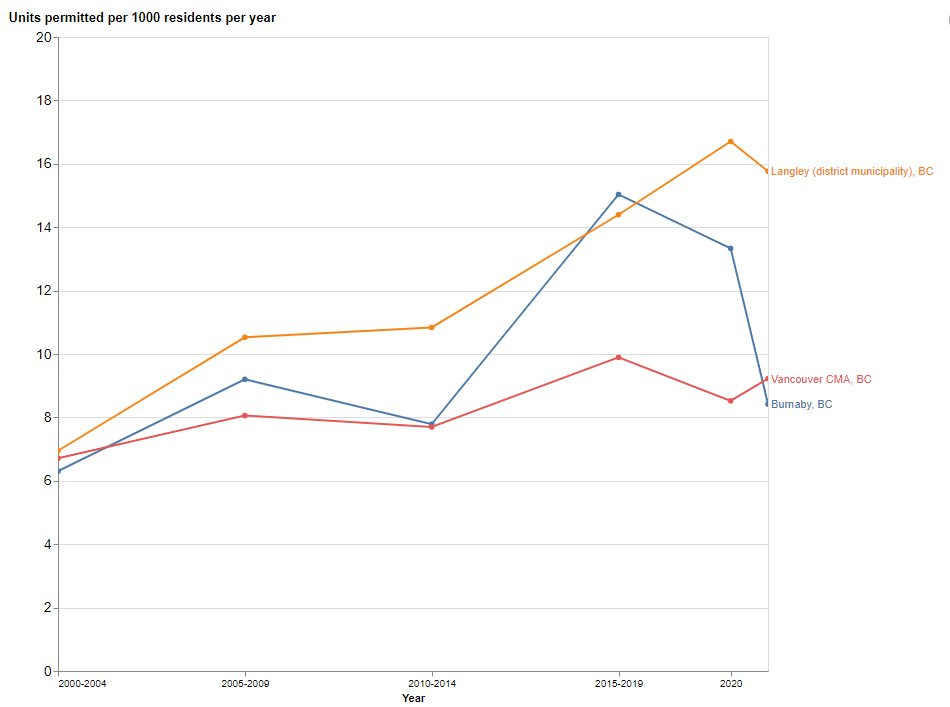

Brendan Dawe provides a similar perspective in a short essay on Twitter, explaining the difference between what the province is aiming for and what Burnaby and Langley have been doing. He observes that they permit a lot of new housing, but they also extract as much revenue as possible, which limits the rate of new building. They’re not trying to build enough housing to drive down prices and rents - as individual municipalities, they can’t. This is what the province is pushing for.

It would be a mistake to say that Langley Township and Burnaby are “anti-housing,” but we should more seriously discuss what the variance between their position and the province’s is.

Burnaby could be described as masters of the old BC planning paradigm - preserve single detached areas; aggressively rebuild brownfields, old apartments, commercial areas in proximity to transit; maximize development charge collections to build up a large fund for improvements.

Langley has a reputation as a sprawl suburb, but the bulk of development has been in multi-unit housing in recent years.

What we have here are two cities who feel (not unjustifiably) that they were doing pretty well under the old paradigm, being made to change by a provincial government that is looking at the big picture.

I think the province is correct, looking at the big picture, and pushing a more broad and systemic policy agenda that necessarily is going to upset some comfortable ways of doing things.

But spare some sympathy for cities who feel like they’ve been working in good faith, achieving good outcomes, being told what to do by Victoria staff who don't know as much as they do about stormwater ponds or what-have-you.

The biggest issue is that BC municipalities have oriented themselves around extracting money from homebuilding, taxes that are facilitated by one-off negotiation, planning discretion, and high prices.

In so far as this system “works,” it works where property taxes are kept low, home-values kept high and voters enjoy new amenities paid for by new home buyers. It’s a high output / high cost equilibrium sustained by high demand to live in the region.

But the flip side is that it’s very difficult for all that new housing to ever compete prices down. Producer surplus which might drive “overbuilding” has already been spoken for by local government.

Together with long, negotiated approval timelines, when prices go up, supply response is necessarily muted. Given recent cost and financing pressures, there's even less surplus to be competed away.

BC municipalities think of themselves as managing the land market through development controls, with the actual housing market being an exogenous force that they have no responsibility for.

What the province is pushing everyone towards is the idea that managing the actual housing market is a key goal, and a goal that is more important than maximizing development revenue.

And this makes sense - any individual city’s ability to affect an inherently regional housing market is limited, and so the individually reasonable equilibrium ends up being to tax homebuilding and maximize discretion while ignoring high prices.

This is why the province has to make rules for every municipality - because by making every city work in concert, they actually can impact regional housing markets, and moreover they have the democratic legitimacy to do so.

Why don’t planners believe that increasing costs makes housing more expensive?

Dan Bertolet provides a similar explanation of the municipal perspective. Yes, red tape and fees do raise the price of housing. Sightline, July 2017.

Few public policy issues can match urban housing politics for its incendiary combination of passion and misconception. To wit: the confounding idea that relaxing regulations and fees to decrease the cost of homebuilding won’t make homes more affordable.

Why? Because, goes the refrain, developers charge as much as the “market will bear” anyway. Any savings from streamlined regulations or reduced fees just yield more profit for the developer, not lower prices or rents.

That reasoning may sound legitimate, but it’s bogus. It misses the forest for the trees—or, the city for the building. Across an entire metropolis, when homebuilding is cheaper, homebuilding speeds up. And in booming, housing-short cities such as Seattle, the more new homes built, the less prices rise—that is, the lower the price the market will bear.

Why does this misconception about costs matter? Because it excuses counterproductive housing policy. Why bother fixing ill-conceived regulations that boost the expense of homebuilding if you believe doing so won’t help affordability? If you believe it just puts more money in developers’ pockets?

What’s more, the confused logic also infects debate over adding costs: if the market sets prices with no regard for cost, it follows that policies that increase the expense of homebuilding can’t raise home prices. This rationale frees policymakers to ignore that imposing impact fees on new homes, for example, is likely to exacerbate their city’s affordable housing crisis.

This sounds very familiar - see Jerry Dobrovolny’s comments to the Metro Vancouver board.

Bertolet provides a diagram that illustrates how lowering costs results in more projects becoming economically viable, which results in more supply and thus lower prices.

The diagram above illustrates the concept. Across a typical city, the potential return on investment (ROI) from homebuilding varies widely depending on site-specific conditions. Each blue bars represents one building site in an imaginary city, with the bar height indicating its potential status quo ROI. The orange bars show how a cost-cutting measure could increase ROI. (It’s an optical illusion that the orange bars are growing to the right—they are all the same length atop the blue bars). In practice there is no precise threshold ROI that makes all projects pencil, but for clarity the diagram depicts an average threshold ROI. Sites with ROI higher than the threshold pencil, and sites with ROI lower, don’t. As delineated by the shaded green area, decreasing the cost expands the number of sites where homes could likely be built.

Policymakers sometimes have reservations about altering regulations to cut costs, worrying that they are just handing windfalls to builders without helping affordability. In the larger picture, though, reducing the cost of homebuilding makes all housing throughout the city more affordable by shrinking the average price the market will bear.

More

Andrew Sancton on development charges. When an individual project faces a cost increase, it can’t pass the increase on to homebuyers and renters. But when all of its competitors face the same cost increase, it can.

Anthem, Polygon, and Canderel voice “deep concern” over Burnaby's new Amenity Contribution Charges. Howard Chai, Storeys, March 2024. “Rob Blackwell of Anthem notes that the current cost of building a one-bedroom, 550-sq. ft home in Burnaby is $678,056, which would be increased to $716,897 [an increase of about $38,000] following the change. For renters, Blackwell notes that the $38,481 would necessitate a rent increase of $129.47 per month ($38,481/12 months x 4% cap rate).” Burnaby city council passed the planned charges unanimously, without much discussion.

The ups and downs of building a real estate development in B.C. Frances Bula, BC Business, January 2024. A step-by-step walkthrough of the development process for a high-rise project in Burnaby. “Burnaby is seen as having a strong planning team that collaborates productively with builders.” But the current city council appears to be more skeptical: in June 2023, they rejected a staff recommendation to allow more density to offset the cost of mandatory below-market rentals. Mayor Mike Hurley is certainly skeptical.

Previous posts on Burnaby: one-day workshop in May 2019, Burnaby multiplexes.

It's a good essay though it's not the whole picture for Langley Township. From 2007-2018 developer fees were heavily suppressed, some of the cheapest in the region, so during that time it wasn't about extracting wealth from developers at all, more about just growing the tax base, with the side effect of producing a bunch of new housing. Now it's different and they have pivoted to a more extractive model, but only because the previous approach led to an infrastructure and facilities deficit.

You've accurately described the single most important roadblock to providing more housing that average people can afford.