Economic analysis of BC's multiplex and transit-oriented policies

If you don't have time to read the 200-page paper, here's a summary

SSMUH and TOA Scenarios in British Columbia, December 2023 (released last Thursday). By Jens von Bergmann, Tom Davidoff, Albert Huang, Nathanael Lauster, and Tsur Somerville.

The BC government has passed legislation to make it legal to build multiplexes across the province (“small-scale multi-unit housing” or SSMUH), and to build apartment buildings close to SkyTrain stations and major bus exchanges (“transit oriented areas” or TOA).

To estimate how much additional housing will result from these changes, the province hired a team to prepare a detailed 200-page analysis, based on economic modelling. The economic modelling is based on detailed parcel-by-parcel information about current land use, information about prices and construction costs in different regions of the province, and experience with land-use reforms in Auckland, Kelowna, the Cambie corridor in Vancouver, and Washington state.

Naturally I wanted to read through the whole thing to figure out how the model works.

Results

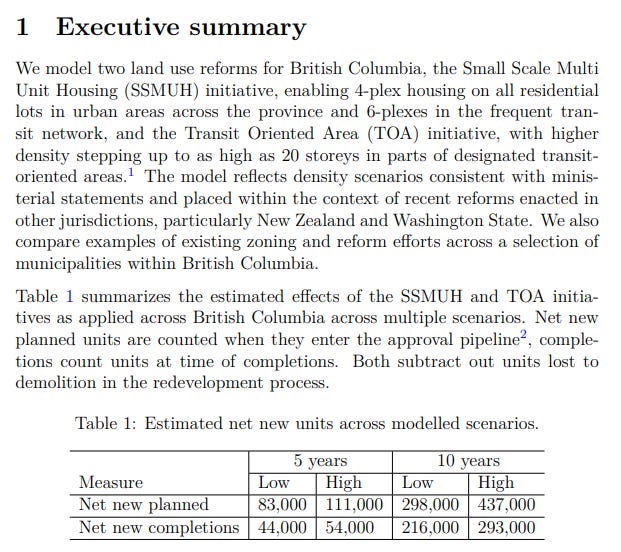

The estimate is that over five years, these policies will result in 44,000 to 54,000 more completed homes province-wide, with prices and rents 6-12% lower compared to without these policies.

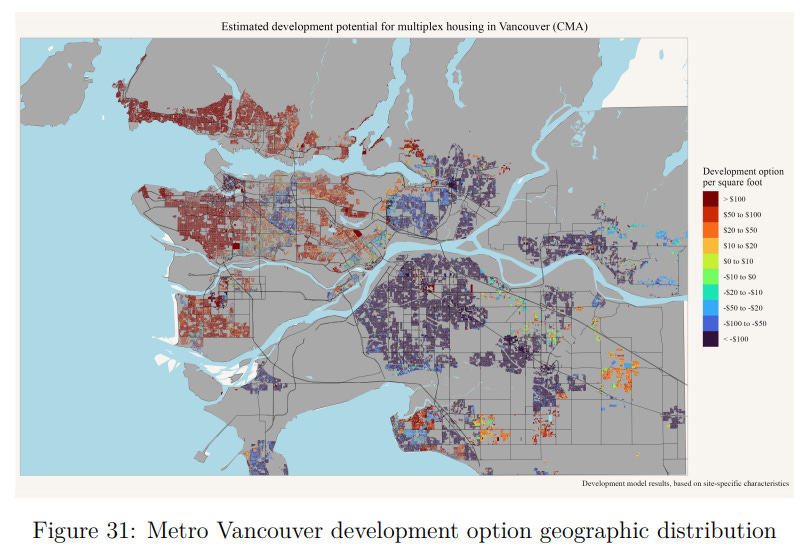

Most of the additional housing comes from the multiplex policy rather than the transit-oriented policy. Many of the transit-oriented areas are already being planned for higher-density development, with height and floor area greater than the provincial guidelines. For example, this applies to most of the Broadway Corridor Plan area: the brown areas in the map below won’t be affected by the provincial policy.

In Metro Vancouver, the areas where it’s economically viable to replace an old single-detached house with a multiplex are shown below. This is based on selling prices and construction costs per square foot. They’re typically areas which are geographically central, with easy access to jobs. Appendix F of the report provides similar maps for other metro regions.

Impact of more housing on prices and rents

How do we know that if we had more housing, prices and rents would be lower?

When we don’t have enough housing, prices and rents have to rise to unbearable levels to keep people out and to force people looking for a place to give up and leave. The usual estimate (“demand elasticity”) is that housing costs have to rise 2% in order to reduce the ratio of people to homes (or more precisely, households to homes) by 1%. Equivalently, if we had 1% more housing than we do, housing costs would be 2% lower. The people who would be able to find a place and move here are people who can’t afford to live here now, but who could (just barely) afford housing costs which are slightly lower.

The paper runs scenarios using demand elasticity values between 1.25% and 2.5%.

A comparison of rents in Auckland (which upzoned in 2016) to other cities in New Zealand:

How the model works

As an interested layperson, my model of how housing works is pretty simple. People want to live and work here, and other people want to build housing for them. There’s three bottlenecks: the approval bottleneck, the cost bottleneck (it only makes sense to build a new building if it’s worth more than the total cost to build it), and the actual construction.

But to actually figure out how much more housing you’re going to get from a policy change, you need a more precise model. The overall model used in the paper looks like this. In turn, each component has its own model.

This model is assuming that approval is no longer a bottleneck. So then redevelopment depends on profitability (green), which depends on the price model and the cost model (blue). It also depends on land being available for sale (“Transaction Probability”) and labour (“Labour Constraints”).

There’s two feedbacks shown from redevelopment, to the price model and the cost model. As redevelopment continues, prices will decline, reducing profitability - a negative feedback loop.

On the cost side, there’s some benefits from “learning by doing”:

In general, permanent increases in construction volume of particular construction types leads to lower real unit costs through greater comfort with type-specific construction processes, more efficient supply chains, and more knowledgeable developers, design professionals, and skilled trades. These are the long run changes that offset or dampen the short run increases in costs that can occur when demand increases quickly before the construction industry adjusts its productive capacity to the new volumes. It is reasonable to believe that as the construction of four and sixplex structures on single family lots becomes commonplace, the inflation adjusted construction costs can come down.

Likelihood of redevelopment

If there’s many properties which could potentially be redeveloped into multiplexes, how can we estimate the likely number each year?

Jens von Bergmann and Joseph Dahmen modelled the likelihood of an old single-detached house in the city of Vancouver being torn down, back in 2018. They have a very cool interactive visualization: Vancouver’s Teardown Cycle.

In short, each property’s value has two parts: the land value and the building value. When you’ve got a property where the land is worth a lot and the building is worth very little, it’s extremely likely that the next time the property is sold, the new owner will tear down the existing building and put up a new one.

From the current paper:

As we show in Appendix B, the rate of single family property transactions hovers between 5% and 10% of the existing stock across regions and years, which gives a baseline to inform future property transactions. In the SSMUH areas and low-density parts of the TOAs we simulate property transactions at historic rates, and assign redevelopment probabilities for each transacted property based on the excess value above cost and expected developer profit generated by redevelopment, heuristically setting redevelopment probabilities at 10% for zero excess value, where existing use competes with new multiplexes, and 90% at $100 per square foot excess value.

The construction workforce will increase, but it’ll take time

The paper assumes that labour will initially be a significant constraint, but over time, the size of the construction workforce will increase. There’s evidence from New Zealand and from the leadup to the 2010 Olympics.

This suggests that labour constraints will become a significant bottleneck once the municipal planning constraints are lifted. Evidence from New Zealand suggests that the labour market will adjust, but that will take time.

Comparing that to longer timelines in British Columbia we note that construction industry share of employees has fluctuated considerably (see Figure 52), most notably in the run-up to the Olympics which triggered a strong labour force response in face of the increase in construction activity. (Somerville and Wetzel 2013)

The ability to build multiplexes will likely result in a re-allocation of construction resources away from single family construction and repair construction, which are most closely connected to multiplex construction. There may also be a smaller shift away from apartment construction into the denser forms based on frame construction. These shifts can help alleviate some of the short-term labour constraints.

Non-market housing projects will also be easier

Some interesting discussion of the benefits for non-market housing projects. The current need to go through a long and painful rezoning process is a major obstacle. Neighbourhood opposition is often even more intense than for market housing. Market housing is attacked for being unaffordable; non-market housing is attacked for being undesirable.

The lack of sites zoned to enable density has been a primary barrier to the construction of more non-market housing. When non-market housing providers are forced to go through rezoning, it adds cost and uncertainty to the development process.

This report does not directly consider non-market housing as part of the proposed reform. However, outright zoning for higher density should greatly increase the viability of non-market housing development across the province. In effect, instead of competing with commercial developers for a narrow range of developable sites, non-market developers will potentially have a much wider range of sites to choose from.

What we want: supply elasticity

“Supply elasticity” basically means the ability of the housing supply to respond quickly, so that when there’s an increase in housing demand we get more housing starts and prices remain stable (like Atlanta), rather than housing starts remaining the same and prices going through the roof (like San Francisco). Small multiplex projects are much faster to plan and build than large high-rise projects.

With multiplexes as an outright development option, with a construction type that has a low barrier of entry, corresponding to a geographic scale that is considerable given the broad prevalence of single family properties by land area, and given the relatively short construction timelines, we anticipate a significant increase in supply elasticity. This means that developers will be able to act fast in response to demand shocks, limiting or even partially reverting dramatic price increases of the sort BC has recently experienced.