I think it’s fair to say that the housing shortage is one of the top challenges facing the Eby government.

The 2023 provincial budget was released last Tuesday. Naturally I read through it looking for housing-related measures. Most of the budget is allocated to health care, education, and social services, but housing gets a fair amount of attention. Besides the 2023-2024 year, the budget also lays out a three-year fiscal plan for revenue and spending.

More capital and operating funding for housing

The most important part: The fiscal plan includes a total of $4.2 billion for housing, over three years. See Table 1.2.2 on page 12.

$1B for additional operating funding through Building BC, which funds both community housing (affordable rentals) and supportive housing (for people who need social supports, not just a place to live).

$700M for additional long-term capital funding: $300M through Building BC and BC Housing, $400M to acquire land for transit-oriented development.

$600M for student housing. An excellent idea, since post-secondary students make up a big chunk of rental demand. (Mike Moffatt has been talking about this for a while.)

$800M for operating funding aimed specifically at reducing homelessness, and $700M for capital funding.

Other measures (“Unlocking more homes and supporting people”), totalling $380M. Some of this is additional funding for existing programs: repair and maintenance of BC Housing’s rental stock ($230M over 10 years), resolution of landlord-tenant disputes through the Residential Tenancy Branch, short-term emergency financial aid through the BC Rent Bank. There’s also a couple new programs: $60M for initiatives to speed up municipal housing approvals, $90M for a pilot program encouraging homeowners to build and rent out secondary suites.

Specific housing projects requiring capital spending are described on pages 52-53.

Renter’s tax credit

This is a refundable tax credit for lower-income renter households, $400 annually, phasing out between $60,000 and $80,000 of household income. It’ll be available starting next year (when people file their 2023 tax returns). Details. See Table 1.2.3 on page 15.

What’s the reason for the tax credit? I think the clearest reason is that there’s an annual $570 grant for owner-occupied housing worth up to $2M. The Green Report notes sardonically:

Our conclusion is that this is a costly program [more than $800M each year] that does not target any group clearly in need or achieve any evident public policy objective.

It’s a straight subsidy to homeowners. Gordon Clark, writing in 2017:

As Vancouver Sun columnist Vaughn Palmer noted last week, the grant was introduced in 1957 by then-Social Credit premier W.A.C. Bennett, arguably the most populist leader in B.C. history, in what was then a very thinly veiled vote-buying scheme paid for with our own cash.

The problem is, when real incomes are falling, asking people to give up an additional $570 per year - however unjustified - will make them very angry (“loss aversion”). It’s a lot easier to raise taxes or reform benefits when the economy is growing and real incomes are rising, so that you’re forgoing part of a gain rather than accepting a loss. (See Joseph Heath’s discussion of degrowth.)

Instead of attempting to take away the benefit to homeowners, it’s easier for the provincial government to provide a roughly comparable benefit to renters. Expected annual cost is $300M.

Property transfer tax reduced for new purpose-built rental

See page 76. The key part:

Effective for transactions that occur on or after January 1, 2024, purchases of new purpose-built rental buildings will be exempt from the further 2 per cent property transfer tax that is applied to the fair market value of the residential component of a taxable transaction that exceeds $3 million. … It further encourages the construction of new purpose-built rental buildings.

2% may not seem like much, but even small changes in costs can make a significant difference to economic viability.

Increase shelter rate

Included in Table 1.2.3: funding to increase the shelter rate for people receiving disability or income assistance (BC’s welfare program for people who can’t work), from $375/month to $500/month. The last time it was increased was in 2007.

Complex-care housing

Homelessness is primarily a housing problem (Aaron Carr). But there’s also high-need street homeless (mental illness, drug addiction, brain injury) who need more than just a place to live - they need intensive 24/7 support.

In January 2022, the province announced that it was going to set up “complex-care housing” for the highest-need cases.

Table 1.2.2 includes $170M for capital funding for complex-care housing. The fiscal plan also includes $100M in operating funding for health services at complex-care sites. See “Complex Care Supports” on page 10.

Daily Hive on complex-care housing:

The provincial government announced today it is initiating complex-care housing, which provides residents with 24/7 wrap-around supports. This is also a step in the direction of the community care type of model that was intended to replace institutionalized care, following the closure of Riverview Hospital.

Unlike supportive housing, complex-care housing provides residents with treatment and specialized care, such as support from nurses, social workers, and other health professionals.

Specific clinical services and other supports include physical, mental health, and substance use care, and psychosocial rehabilitation, as well as proper food nutrition, social and community supports, and personal care and living supports.

Other capital and operational spending

Transportation. There’s a close connection between mobility and housing - people want to live where they have access to jobs, and that depends on transportation. See Table 1.7 on page 52. The fiscal plan includes $13B for transportation capital spending over three years, including $1.2B for the Broadway Subway and $1.5B for the SkyTrain to Langley.

Biking. It’s called “active transportation,” but I think that mostly means biking. $100M over three years, “to help local governments improve active transportation infrastructure, such as building connecting sidewalks, installing bike lanes, and building multi-use paths in parks.” See Table 1.2.5 on page 20.

Schools. As new housing is added to a neighbourhood, it’s important to build up public services like schools and community centres. I was wondering if the budget would include funding for the planned school at Olympic Village, but it doesn’t.

Public safety. An important aspect of livability in an urban setting. (Noah Smith: “Walkability is punchability.”) The fiscal plan includes $460M in additional funding for public safety over three years, including $230M for policing, and $90M specifically to deal with repeat violent offenders. See Table 1.2.4 on page 18.

Economic outlook

Commentary on housing from the Economic Forecast Council, pp. 118-119:

Housing supply and affordability issues were another key topic of discussion. Most Council members noted housing as one of the most pressing issues. While several highlighted that the issue of housing affordability in B.C. pre-dated COVID-19, tight supply paired with extremely low mortgage rates and the shift towards remote work exacerbated the housing affordability challenge further. In order to tackle this issue, most members indicated the need to continue to work towards expanding the housing supply. Continuing to expand purpose-built rentals and remove barriers to home building (such as local zoning rules and slow approval processes) were some of the possible measures suggested to help address housing affordability.

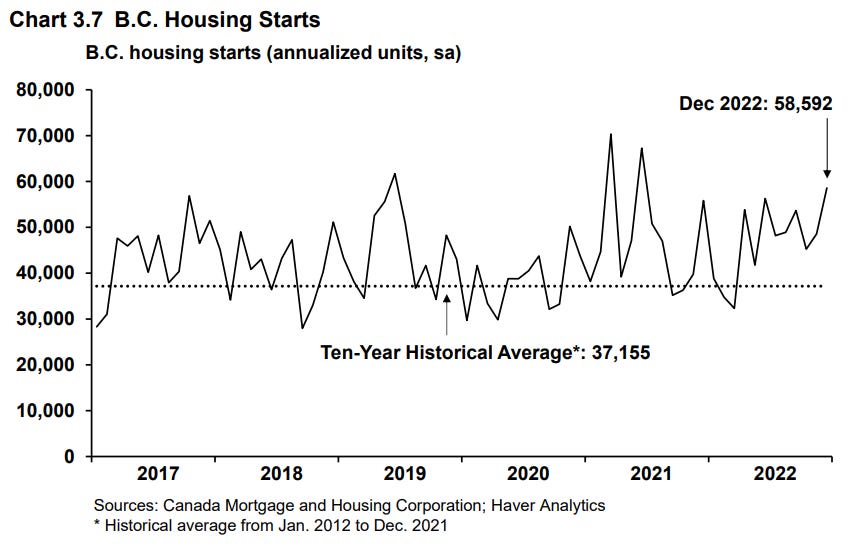

Housing starts in 2022 are down compared to 2021 (a record year). Interest rates are bringing down prices and raising costs, which makes fewer projects economically viable.

The number of sales is dropping much faster than prices. (This isn’t surprising - prices are “sticky downward,” i.e. sellers are reluctant to lower their prices, so it takes a long time.)

There’s also a graph showing what’s happening to prices in Greater Vancouver specifically. Same pattern, with a much higher run-up in the price of detached houses compared to apartments.

What else?

Besides spending money on building housing, what else can the provincial government do? Looks like we’ll find out pretty soon:

Together, these investments will help support several actions in a refreshed housing strategy, set to be released by the Province in spring 2023.

Links

BC Budget 2023 - government website

Vancouver Sun: coverage of the budget, and housing specifically.

Previously: BC setting housing targets for municipalities.