Stuart Donovan and Matthew Maltman, Dispelling myths: Reviewing the evidence on zoning reforms in Auckland. Land Use Policy, April 2025.

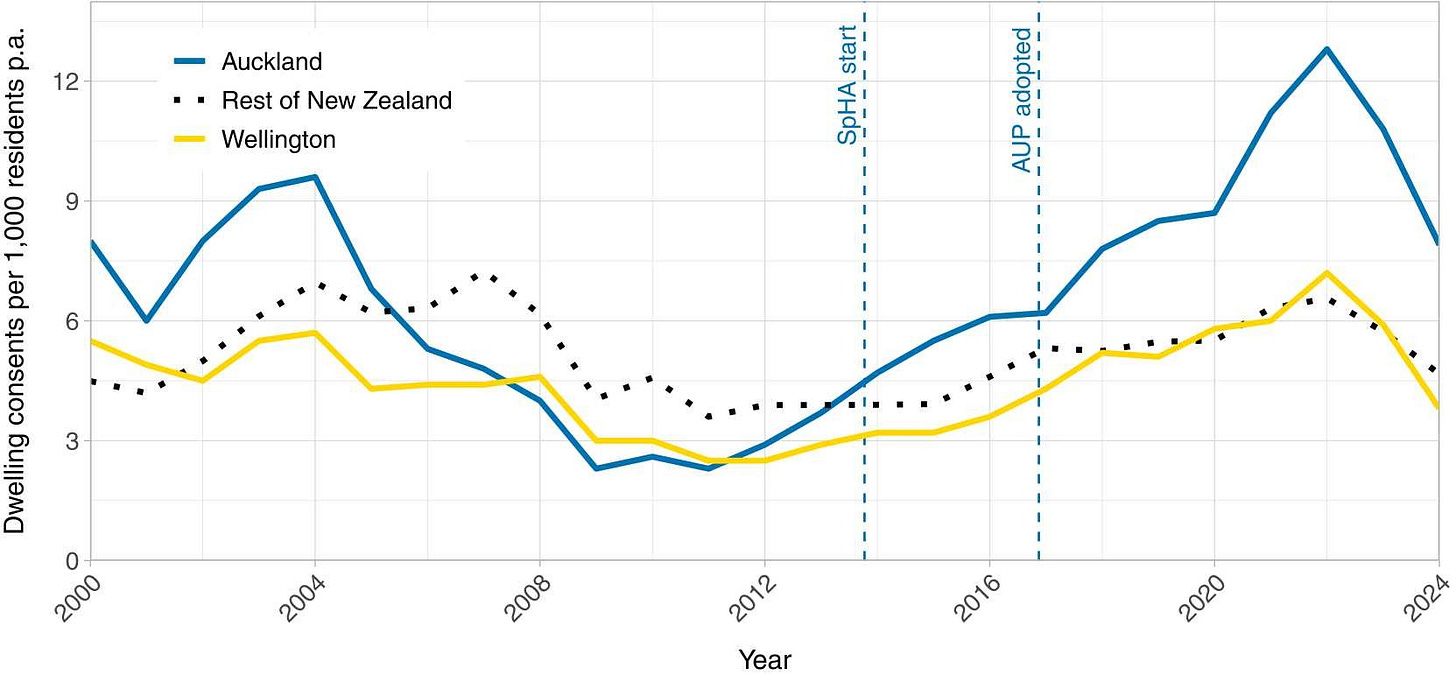

Auckland’s broad upzoning in 2016 resulted in (a) much more housing being built, and (b) lower rents, as shown by a number of studies co-authored by Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy.

Two economists, Cameron Murray and Tim Helm, argued that these studies were flawed. Matthew Maltman reviewed Murray and Helm’s arguments and concluded that they didn’t hold up. This debate took place via blog posts and social media.

Donovan and Maltman’s peer-reviewed paper makes the case at greater length. As a layperson, it seems clear and convincing to me.

Given that Murray and Helm have published their comments via informal channels and subsequent sections of this paper find them to have little to no merit, readers may wonder why these critiques would warrant our attention. We have three main reasons for wanting to formally document and assess Murray and Helm’s critiques in this paper.

First, Murray and Helm have cited their blog posts in their submissions to formal policy and planning processes. Helm (2024b), for example, cited Murray and Helm (2023a) in evidence submitted to a planning process in Wellington, New Zealand. This evidence appears to have swayed Commissioners in this process, who determined that planning policies did not play a “dominant role in housing affordability” in Wellington. Similarly, a parliamentary inquiry in Australia concluded that the evidence on Auckland’s upzoning was contested, citing evidence submitted by Murray. Given their apparent influence on policy and planning processes, we consider there is a public interest in formally documenting and assessing Murray and Helm’s critiques in this paper.

Second, many of Murray and Helm’s critiques diverge from the wider economic evidence. Not only is there robust quasi-experimental evidence that upzoning increased housing supply and reduced rents in Auckland, but this evidence dovetails with a large number of other economic studies that also find planning policies can affect both the supply and price of housing. The combined weight of this evidence, moreover, appears to have persuaded a majority of economists. In a survey of notable economists conducted by the Economic Society of Australia, 65 % of respondents believed ‘easing planning restrictions’ is one of the top 3 measures that governments can take to improve housing affordability. Similarly, a survey undertaken by the New Zealand Association of Economists found around 95 % of respondents believed that land use restrictions reduced housing supply and affordability. In this context, we see value in contrasting Murray and Helm’s critiques with the wider economic evidence.

Third, this episode raises questions about how planning processes engage with economic evidence. In our view, the adverse influence of Murray and Helm’s critiques provides a timely reminder of the value of more formal literature, such as working papers and peer-reviewed articles, compared to informal channels, such as blog posts and online comments. While formal literature is not immune to mistakes and misrepresentations, such problems are more likely to be identified and addressed — whether by the original researchers, peer reviewers, journal editors, or subsequent researchers. Interestingly, the Commissioners in Wellington admitted under questioning their decisions were informed more by Helm’s oral testimony than his written evidence. If the Commissioners had instead put more weight on Helm’s written evidence, then they might have noticed that it relied heavily on a blog post that he had co-authored, rather than more formal sources. By documenting some of the most egregious errors that affect Murray and Helm’s informal critiques, we hope to stimulate debate on how planning and policy processes can best engage with economic evidence.